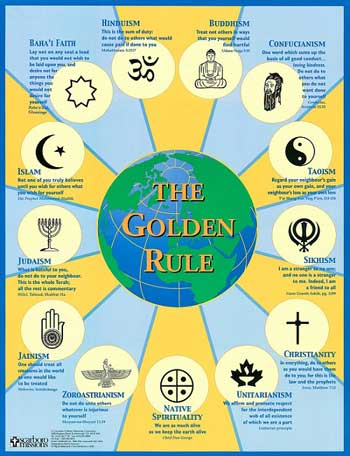

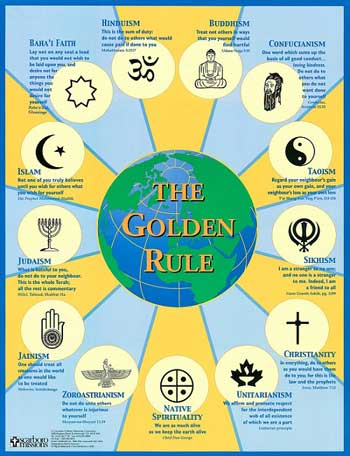

“The Golden Rule was original to Christ and is unprecedented and unparalleled in the history of ethics.”

—Peter May, Testing the Golden Rule

“Almighty God and Christianity and the Bible professes ‘DO unto others,’ not, ‘do NOT do unto others.’”

—An Evangelical Christian explaining why he thinks Christianity alone is positive while all other teachings appear negative

Not a few evangelical Christian apologists argue that their religion is superior because Jesus preached the Golden Rule, “All things therefore that you want people to DO to you, DO thus to them” (Matthew 7:12), while other ancient teachers merely taught the negative version of that rule: “Do NOT do unto others what you would NOT like done to yourself.” Christian apologists C.S. Lewis and William Barclay even cited numerous quotations of the negative Golden Rule from ancient sources to make the contrast appear more stark between what Christianity taught and what the rest of the world taught:

“Do not impose on others what you do not desire others to impose upon you.” (Confucius, The Analects. Roughly 500 BCE.

Hindu sacred literature: “Let no man do to another that which would be repugnant to himself.” (Mahabharata, bk. 5, ch. 49, v. 57)

“Hurt not others in ways you yourself would find hurtful.” (Udana-Varga, 5.18)

Zoroastrian sacred literature: “Human nature is good only when it does not do unto another whatever is not good for its own self.” (Dadistan-I-Dinik, 94:5; in Muller, chapter 94, vol. 18, p. 269)

Buddhist sacred literature: “Hurt not others in ways that you yourself would find hurtful.” (Udanavargu, 5:18, Tibetan Dhammapada, 1983)

The Greek historian Herodotus: “If I choose I may rule over you. But what I condemn in another I will, if I may, avoid myself.”

(Herodotus, The Histories, bk. III, ch. 142. Roughly 430 BCE.)

Isocrates, the Greek orator: “What things make you angry when you suffer them at the hands of others, do not you do to other people.”

Christian apologists add that it is not (in their opinion) difficult to honor a negative Golden Rule, but it is “exceedingly” difficult to live by the positive Golden Rule Jesus taught. Such apologists seem to forget that a lot of Judeo-Christian morality is based on the “Ten Commandments,” which are almost all negative rules, “Thou shalt NOT…“ etc. Such apologists even forget that Jesus and Saint Paul are said to have struggled hard to resist temptation and resist sinning, i.e., to NOT do things they were tempted to do, again a negative task. The whole story of Job is about a man tempted to “curse God,” but he resists. So, for Jesus, Paul, Job and other Biblical heroes, there appears to be just as much “difficulty” involved in avoiding sinful behaviors as practicing positive ones, (perhaps even greater “difficulty”) regardless of what the apologists state.

Indeed, the so-called “negative” Golden Rule is itself a part of Christianity. It is found in pre-Christian Jewish writings as well as in the Catholic Bible and in a textual variant in the Book of Acts, see these examples:

Philo, a Jewish philosopher in Alexandria, wrote, “What you hate to suffer, do not do to anyone else.”

Hillel, a Jewish rabbi who lived just before Jesusʼ day, taught, “What is hateful to thee, do not to another. That is the whole law and all else is explanation.” (b Shabbatt 31a; cf. Avot de R. Natan ii.26)

Even earlier than the saying by rabbi Hillel, the negative Golden Rule is found in Tobit, an apocryphal book that is included in the Catholic Bible: “What you hate, do not do to anyone.” (Tobit 4: 14-15. 2nd century BCE.)

The negative golden rule is also found in the Book of Acts: “Textual variants in Acts 15 :20,29 & 21:25 are quite involved… various Western texts add the Negative Golden Rule, ‘Do not do unto others…’ which is attributed to the first century Jewish rabbi Hillel and also quoted in The Didache (a second century Christian text believed to consist of teachings of the earliest Christian Fathers and used to teach new converts) i.2.” [from Tim Hegg and Beit Hallelʼs online article, “Acts 15 and the Jerusalem Council: Did They Conclude the Torah was Not For Gentiles?” copyright 2001 www.torahresource.com]

But what about the claim made by Christian apologists, such as William Barclay, who argued, “The very essence of Christian conduct is that it does not consist in not doing bad things, but in actively doing good things.” Was Barclay unaware of the fact that teachings that advocate “actively doing good things” are found in other ancient literature besides the New Testament?

Ancient Babylonian sacred teaching from two thousand years before Jesus was born: “Do not return evil to your adversary; Requite with kindness the one who does evil to you, Maintain justice for your enemy, Be friendly to your enemy.” (Akkadian Councils of Wisdom, as cited in Pritchardʼs Ancient Near Eastern Texts)

Buddhist holy teaching: “Shame on him who strikes, greater shame on him who strikes back. Let us live happily, not hating those who hate us. Let us therefore overcome anger by kindness, evil by good, falsehood by truth.” (written centuries before Jesus was born)

Buddhist holy teaching: “In this world hate never yet dispelled hate. Only love dispels hate. This is the law, ancient and inexhaustible.“ (The Dhammapada)

Taoist holy teaching: “Return love for hatred. Otherwise, when a great hatred is reconciled, some of it will surely remain. How can this end in goodness? Therefore the sage holds to the left hand of an agreement but does not expect what the other holder ought to do. Regard your neighborʼs gain as your own and your neighborʼs loss as your own loss. Whoever is self-centered cannot have the love of others.” (written centuries before Jesus was born)

The Greek poet Homer: “I will be as careful for you as I should be for myself in the same need.” (Calypso, to Odysseus, in Homer, The Odyssey, bk. 5, vv. 184-91. Roughly late 8th century BCE.).

Excerpts from a paganʼs prayer: “May I be the friend of that which is eternal and abides…May I love, seek, and attain only that which is good. May I wish for all menʼs happiness…May I reconcile friends who are wroth with one another. May I, to the extent of my power, give all needful help to all who are in want. May I never fail a friend in danger…May I know good men and follow in their footsteps.” (“The Prayer of Eusebius,” written by a 1st-century pagan, as quoted in Gilbert Murray, Five Stages of Greek Religion. Interesting Note: A few Christians on the internet have incorrectly attributed this prayer to a 3rd-century Christian also named Eusebius. They should read Murrayʼs book instead of assuming that everything positive has to be “Christian.”)

Islamic holy teaching: “That which you want for yourself, seek for mankind.” (Sukhanan-i-Muhammad, 63)

The Positive Golden Rule is also found in Jewish literature (Mishneh Torah ii: Hilekot Abel xiv.I)

Lastly, there appears to be a flaw in the Golden Rule itself. If you simply try to “do unto other as you would like them to do unto you” then you could wind up doing things to others they might not enjoy as much as you do! For instance, think of all the things you like and think what would happen if you started “doing them” to others without first considering whether or not those others like all of the same things you do. People have different “likes” in clothing, food, music, books, and religion, and so doing to others what YOU like might not be something THEY like. (One hypothetical worst case scenario of attempting to “do unto others what YOU would like done unto yourself,” might be if someone LIKES heaven but fears they will be sent to eternal hell for doubting a particular religious belief, so they might hypothetically agree that they LIKE the idea of having others coerce them to “correct” their beliefs to avoid hell and get to heaven. In that hypothetical case the Golden Rule would imply that other people would be equally appreciative of being “corrected”—even via coercion—rather than “risk eternal hellfire.”) So perhaps we need both the Golden Rule and also the “negative” Golden Rule, working together, to avoid imposing our LIKES on others who do not share them.

An even more finely tuned rule might be what some call “The Platinum Rule,” namely, “Do Unto Others as THEY Would Have You Do Unto Them.” In other words, take time to learn about your neighborʼs tastes, their mood, their nature, and their temperament, before you start “doing” things “unto them.” Treat others the way THEY want to be treated.

In all three cases — the Golden Rule, the negative Golden Rule (also nicknamed the “Silver Rule”), and the “Platinum Rule” — our shared biological and social/psychological structure ensures that we share similar desires and fears. And such similarities are what allow each of us a window into each othersʼ inner self. Very few people enjoy being lied to, called names, stolen from, injured, or otherwise provoked. While almost every last one of us loves having friends, sharing experiences, good health, good meals, etc. Those are part of who we all are. Hence, “you” have an inner window on what other people would like done to them. Just keep in mind that the exact “scene” that is displayed most prominently inside each personʼs “inner window” may differ from person to person, and should be taken into account before you “do unto them” as “they” would like.

Addenda

For some Christian online apologists, following the “Golden Rule” applies to how one ought to conduct oneʼs self in discussion with others, even when contending for the faith with atheists and people of other religions. See for instance, The Golden Rule Apologetic by Bob Passantino.

But other Christian online apologists such as J.P. Holding at Theology Web, and Steve Hays at Triablogue, revel in name-calling and mockery when contending for the faith with atheists, Catholics (and each other, as one can see in a debate that took place between Holding and Hays on predestination). Holding finds precedent for his "riposte" style in the Scriptures themselves, in the manner in which OT prophets, as well as Jesus and Paul in the NT, spoke against those with other beliefs.

So what does the Bible really teach concerning the Golden Rule and Christian practice in debate? Whose interpretation is correct? Passantinoʼs or Holdingʼs?