First, what do Christians want? Christians (and other believers in a personal higher power) want clarity, fewer grey areas, more black and white regions, a roadmap to life, a roadmap to eternity, certainty. Feeling one is certain about something is an addictive feeling that tends to reinforce itself, and people argue the most over topics where certainty does not exist such as religious and political views—perhaps because people are capable of living in many different types of societies and holding a wide varieties of beliefs including a firm belief in how things must turn out in the future provided we do such and such.

Christians donʼt want to be alone, they want a person who is guaranteed to be with them always, who hears their cries, even If those cries are not always answered, even if the Xn has to interpret what the answer to their prayers are (such as answered quickly, slowly, fully, partially, or, keep praying and maybe they will be answered, or, forget about that prayer and start praying for something else), but regardless of having to interpret such answer to prayer for themselves, the Christian is sure someone is there, so they are never alone.

Christians want all human suffering and pain to make sense, to eventually be accounted for, either in the form of punishment for the person who has made others suffer, or as blessings granted sooner or later to the one who has suffered, or if not added blessings, then they want such suffering to have been a soul building experience rather than a soul weakening or deconstructing experience like post traumatic stress disorder (or to coin a more Christian sounding term, “post traumatic spiritual stress disorder”). And they want not just a balanced account book for human suffering, an eye for an eye, but something more—forgiveness and healing for all of their own sins, feelings of guilt and pain.

Lastly, the Christian wants human death to be an illusion (some also want the death of believed pets to be an illusion). They want to be immortal like the personal higher power they worship.

What do atheists want?

Do atheists want the reverse of what Christians want? No. Atheists like feeling certain about many things, they prize knowledge, they donʼt want to be alone, and as humanists they are in favor of justice, equality, reducing suffering, aiding healing, and human life extension. Atheists however hold more modest views in those areas than those who are certain that a higher power exists.

Atheists and Christians also agree to some extent that there are plenty of people with their own individual concerns who fail to live up to humanist or Christian ideals, who fail to think big, embrace larger visions, wider feelings of empathy. Those people might be caught up in a daily struggle to make ends meet, wage slaves who earn only a few dollars a day in third world countries, migrant workers in the U.S., or even people with well paying jobs but whose debts or hospital bills have risen and they are struggling to keep their heads above financial water. While other people are locked into repetitious jobs for decades that no longer feed their mental reservoir of wider interests, curiosities and knowledge they possessed when they were young and which continue to atrophy away, so there are plenty of people who might never develop much of a thirst for knowledge, certainty or global justice. While still other people grow addicted to a wide variety of beliefs, thoughts, substances and behaviors, overlooking broader concerns or the needs of others, since the brain can reward itself with little blasts of pleasurable chemicals for all kinds of thoughts and behaviors, including many that do not benefit either the individualʼs health or well being, or society as a whole.

In fact, religions and philosophies (notably political philosophies) of various types can be so addictive that attempting to win an argument is more important than maintaining a friendship, a family, or peace on earth.

Religious people like everyone else can also fall into repetitious patterns that slowly rob them of flexibility of mind, or they can fall into addictive behaviors of all sorts. They can become beer and football Christians, nominal churchgoers. There are also plenty of discouraged Christians, some suffering post traumatic faith disorders. Not to mention the existence of many restless, semi-disenchanted, questioning, progressive, humanistic, very moderate to liberal or even universalist and mystical Christians,

On what I would call the brighter side, many Christians are mingling with atheists than ever before, not just on the internet, but you sometimes find churches opening their doors to a discussion of uncertainties of belief, even inviting debates with atheists. People are getting to know one another, atheists and Christians, sharing fears, failures, wishes, hopes and dreams.

What I find ironically hopeful is that no matter what side one is on in a religious or political debate, both sides are often full of energy and happy, knowing the challenge ahead, of trying to fully communicate their point of view, all they know and believe about a topic, in summary of course, to people who are less than eager to agree with it. Humans enjoy not simply holding ideas in their heads, but sharing them with others, and it is a joy when given the chance to do so. Also, for those who love a challenge, “preaching to the choir” appears to be less of a joy than engaging in a debate.

What is the meaning of life for Christians and atheists?

Christians think of meaning as coming from an eternal God. Things that do not last, called temporal things, have little meaning. However, many ancient Jewish writings depict human life as temporary, all die and go to the same place, a land of shadows called “Sheol” (with only a few exceptions like Enoch or Elijah who get to live with Yahweh in heaven, but even the Greeks had a few exceptions, with everyone else winding up in Hades after they die). The immortality of humans is not assumed throughout ancient Jewish writings, many writers of whom found meaning in temporal existence, looking forward to blessings from Yahweh in this life and then blessings on oneʼs descendants, nation, people, race that live on after one has died.

Also, many Christians believe that worshiping God is not enough to give oneʼs life meaning, because it has to be the right God, the Trinitarian creedal Christian God, otherwise one risks being damned eternally (universalist Christians would not agree with that statement, but most Christians are not universalists). So the meaning of life consists largely in avoiding hell and being assured of heaven by worshiping the one true God, and nothing in life matters more or holds more meaning than making a “decision” to follow and believe in the Trinitarian creedal Christian God, the author of such assurances.

Atheists do not find meaning in becoming an adherent of a belief system that must continue being “sold” in all of its original exclusivity because if no further “sales” are made then many wonderful and interesting people one has grown to love and respect will be damned for eternity. That sounds too much like a pyramid scheme erected on fear.

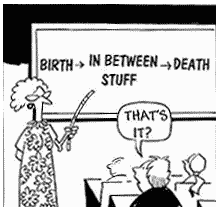

The atheist idea of meaning is more modest, along the lines of using reason and foresight to obtain the necessities and joys of life for themselves and others. Many atheists are also happy simply to see more moderate points of view in religion flourishing.

Atheists also recognize that most experiences in life are temporary, like enjoying ice cream. Memories tend to fade over time. And we see living things dying all around us. But that does not make such experiences, memories and life, meaningless, but precious.