Dear Christian Friend,

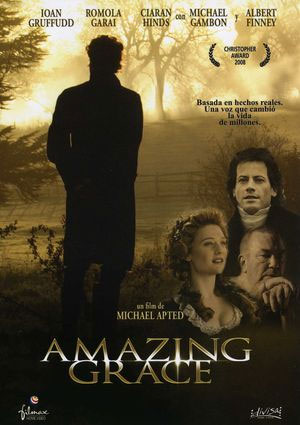

Thank you for your invitation [reproduced at the end of this email] to see the movie releasing this weekend, titled, “Amazing Grace,” about the part played by a Christian in the abolition of slavery in Great Britain. Like you I hope such a film will inspire others to become more socially and politically active. (Of course there are many stories round the world of peopleʼs actions that have inspired others to help their fellow human beings, and I endorse pretty much all of them that have value in that respect, regardless of religious or non-religious content.) On the other hand Iʼm also reminded of how films of all sorts, produced by all kinds of people, also tend to leave a lot out. Speaking of which, I have much to add concerning the “God and slavery” issue, even concerning the abolition of slavery in Britain, Wilberforce, John Newton (the former slave trader who wrote “Amazing Grace”—the song whose title was also used as the name of the upcoming film), and Americaʼs “Holy War,” the Civil War, which proved that relying on the Bible and Biblical theologians to decide moral questions (such as the question of slavery) was not enough.

Firstly, John Newton…

“Editorʼs Bookshelf: Amazing Myths, How Strange the Sound: An interview with Steve Turner, the author of Amazing Grace: The Story of Americaʼs Most Beloved Song” by David Neff, Christianity Today, March 31, 2003)

John Newton was a pastor and author of “Amazing Grace” and “Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken.”…

INTERVIEWER: What mythology did you yourself hold that you discovered was wrong when you did your research?

TURNER: I think I just knew the basic skeleton of this story. I knew Newton was a slave trader, I knew that he had been in a storm, and I knew heʼd written a song. I didnʼt really know the sequence in which that happened. Arlo Guthrie tells the story on stage that Newton was transporting slaves and the storm hit the boat, he was converted on the spot, changed his mind about slavery, took the slaves back to Africa, released them, came back to England, and wrote the song. That would be nice. That would be the way weʼd like to write the story. But the fact is that he took years and years before he came to the abolition position. And he never captained a slave ship until after he became a Christian. All his life as a slave captain was actually post-conversion.

The majority of Christians were in favor of the slave trade. The ship owner that he worked for had a pew in the church in Liverpool. It was not uncommon at all for prominent Anglicans to also be involved in the slave trade. And it made me wonder, what things are we involved in that we think are fine but in centuries to come people will think, How could they possibly have done that? […]

Newtonʼs tender ship captainʼs letters that he sent home to his beloved Mary showed complete lack of concern for the African families he was breaking up. A telling passage from one letter cites “the three greatest blessings of which human nature is capable” as “religion, liberty, and love.” But referring to those he had helped to enslave, he wrote, “I believe… that they have no words among them expressive of these engaging ideas: from whence I infer that the ideas themselves have no place in their minds.”

When it came to denouncing the slave trade, Newton would not commit himself publicly until the mid-1780s—nearly 30 years after the issue was first broached in Parliament, 20 years after the Countess of Huntingdon began campaigning for equal treatment of the races, and 14 years after John Wesley wrote his Thoughts on Slavery.

Secondly, The Abolition Of Slavery In Britain And The U.S.

By the late middle ages, the slave trade was a most lucrative business. Protestant England was just as guilty in condoning and promoting the slave trade as were the Catholic countries. In fact one particularly devout trader, one Captain Hawkins, actually named one of his ships “Jesus” and regularly preached the love of Christianity to his crew and human cargo. When slavery was finally banished from England it was due to the influence of secular law and the decision was opposed by the church hierarchy… It is not a coincidence that the freedom of the slaves across the world occurred at the same time that the church was losing its stranglehold on the state.

Jon Nelson, “Christianity, Racism and Slavery” [online] The Atheist Alliance Web Center

It is certainly true that the campaign against slavery and the slave trade was greatly strengthened by [some] Christian [individuals], including the Evangelical layman William Wilberforce in England and the Unitarian minister William Ellery Channing in America. But Christianity, like other great world religions, lived comfortably with slavery for many centuries, and slavery was endorsed in the New Testament. So what was different for antislavery Christians like Wilberforce and Channing? There had been no discovery of new sacred scriptures, and neither Wilberforce nor Channing claimed to have received any supernatural revelations. Rather the eighteenth century has seen a widespread increase in rationality and humanitarianism, which led others—for instance, Adam Smith, Jeremy Bentham, and Richard Brinsley Sheridan [and Thomas Paine in America]—also to oppose slavery, on grounds having nothing to do with religion. Lord Mansfield, the author of the decision in Somersettʼs Case, which ended slavery in England (though not its colonies), was no more than conventionally religious, and his decision did not mention religious arguments. Although Wilberforce was the instigator of the campaign against the slave trade in the 1790s, this movement had essential support from many in Parliament like Fox and Pitt, who were not known for their piety. As far as I can tell, the moral tone of religion benefited more from the spirit of the times than the spirit of the times benefited from religion.

Where religion did make a difference, it was more in support of slavery than in opposition to it. Arguments from scripture were used in Parliament to defend the slave trade.

Steven Weinberg, “A Designer Universe?” New York Review of Books, Oct. 21, 1999

It is impossible for any well-informed Christian to deny that the abolition movement in North America was most steadily and bitterly opposed by the religious bodies in the various States. Henry Wilson, in his Rise and Fall of the Slave Power in America; Samuel J. May, in his Recollections of the Anti-Slavery Conflict; and J. Greenleaf Whittier, in his poems, alike are witnesses that the Bible and pulpit, the Church and its great influence, were used against abolition and in favor of the slave-owner.

I know that Christians in the present day often declare that Christianity had a large share in bringing about the abolition of slavery, and this because men professing Christianity were abolitionists. I plead that these so-called Christian abolitionists were men and women whose humanity, recognizing freedom for all, was in this in direct conflict with Christianityʼs [teachings concerning the subjugation of slaves to their masters].

It is not yet fifty years since the European Christian powers jointly agreed to abolish the slave trade. What of the effect of Christianity on these powers in the centuries that had preceded? The Christian heretic, Condorcet, pleaded powerfully for freedom for slaves whilst Christian France was still slave-holding. For many centuries Christian Spain and Christian Portugal held slaves. Puerto Rico freedom is not of long date: and Cuban emancipation is even yet newer. It was a Christian King, Charles V, and a Christian friar, who founded in Spanish America the slave trade between the Old World and the New. For some 1800 years, almost, Christians kept slaves, bought slaves, sold slaves, bred slaves, stole slaves. Pious Bristol and godly Liverpool less than 100 years ago openly grew rich on the traffic. During the ninth century Greek Christians sold slaves to the Saracens. In the eleventh century prostitutes were publicly sold as slaves in Rome, and the profit went to the Church.

It is said that William Wilberforce, the famed British abolitionist, was a Christian. But at any rate his Christianity was strongly diluted with unbelief [in the literal words of the Old Testament]. As an abolitionist he did not believe Leviticus 25: 44-6; he must have rejected Exodus 21: 2-6; he could not have accepted the many permissions and injunctions by the Bible deity to his chosen people to capture and hold slaves. In the House of Commons on 18th February, 1796, Wilberforce reminded that Christian assembly that infidel and anarchic France had already given liberty to its African slaves, whilst Christian and monarchic England was “obstinately continuing a system of cruelty and injustice.” Wilberforce, whilst advocating the abolition of slavery, found the whole influence of the English Court, and the great weight of the Episcopal Bench, against him. George III, a most Christian king, regarded abolition theories with abhorrence, and the Christian House of Lords was utterly opposed to granting freedom to the slave …

When William Lloyd Garrison, the pure-minded and most earnest abolitionist, delivered his first anti-slavery address in Boston, Massachusetts, the only building he could obtain, in which to speak, was the infidel hall owned by Abner Kneeland, the “infidel” editor of the Boston Investigator, who had been sent to jail for blasphemy. Every Christian sect had in turn refused Mr. Lloyd Garrison the use of the buildings they controlled. Lloyd Garrison told me himself how honored deacons of a Christian Church joined in an actual attempt to hang him. [Garrison, like the most radical abolitionist Quakers of his era, was deeply religious yet also deeply distrustful of churches and their ecclesiastical organizations, perhaps because the churchmen of his day thought that it was more important for the government to forbid all mail deliveries on “Sunday” than to forbid slavery. Garrison himself found out later in life that he agreed with much of the reasoning of the “infidel” Thomas Paine, regarding both Paineʼs questioning of institutionalized religion and of the Bible. Garrison later embraced the “natural religion” of Paine—one rejecting miracles, mysteries, and ecclesiastical hierarchies, and insisting on total separation of church and state.—Susan Jacoby, Freethinkers: A History of American Secularism]

When abolition was advocated in the United States in 1790 the representative from South Carolina was able to plead that the Southern clergy did not condemn either slavery or the slave trade, and Mr. Jackson, the representative from Georgia, pleaded that “from Genesis to Revelation” the Bible remained favorable to slavery.

Elias Hicks, the brave Abolitionist Quaker, was denounced as an atheist. And, less than twenty years ago a Hicksite Quaker was expelled from one of the Southern American Legislatures, because of the reputed irreligion of abolitionist Quakers.

When the “Fugitive Slave Law” was under discussion in North America [a law that demanded all runaway slaves be returned to their masters who then got to punish them grievously for escaping], large numbers of Northern clergymen of nearly every denomination were found ready to defend this infamous law.

Samuel James May, the famous Northern abolitionist, was driven from the pulpit as irreligious, solely because of his attacks on slave-holding. Northern clergymen tried to induce “silver tongued” Wendell Phillips to abandon his advocacy of abolition. Southern pulpits rang with praises for the murderous attack on Charles Sumner. The slayers of Elijah Lovejoy were highly reputed Christian men.

The Christian historian, Guizot, notwithstanding that he tries to claim that the Church exerted its influence to restrain slavery, says (European Civilization, Vol. 1., p.110)” “It has often been repeated that the abolition of slavery among modem people is entirely due to Christians. That, I think, is saying too much. Slavery existed for a long period in the heart of Christian society, without its being particularly astonished or irritated. A multitude of causes, and a great development in other ideas and principles of civilization, were necessary for the abolition of this iniquity of all iniquities.” My contention is that this “great development in other ideas and principles of civilization” was long retarded by governments in which the Christian Church was dominant. The men who advocated liberty were imprisoned, racked, and burned, so long as the Church was strong enough to be merciless.

The Rev. Francis Minton, Rector of Middlewich, in his recent earnest volume [Capital and Wages, p.19] on the struggles of labor, admits that “a few centuries ago slavery was acknowledged throughout Christendom to have the divine sanction… Neither the exact cause, nor the precise time of the decline of the belief in the righteousness of slavery, can be defined. It was doubtless due to a combination of causes, one probably being as indirect as the recognition of the greater economy of free labor. With the decline of the religious belief in the divine sanction and righteousness of slavery, its abolition took place.”

The institution of slavery was actually existent in Christian Scotland in the seventeenth century, where the white coal workers and salt workers of East Lothian were chattels, as were their Negro brethren in the Southern States thirty years since; they “went to those who succeeded to the property of the works, and they could be sold, bartered, or pawned.” [Perversion of Scotland, p.197.] “There is,” says J. M. Robertson, “no trace that the Protestant clergy of Scotland ever raised a voice against the slavery which grew up before their eyes. And it was not until 1799, after republican and irreligious France had set the example, that it was legally abolished.”

Charles Bradlaugh, Humanityʼs Gain From Unbelief (1889 & 1929) [online]

The Second Great Awakening [a Christian revival movement], beginning around 1800 in America, is sometimes cited as an important causative factor in the abolitionist movement that followed… The implication here is that Christianity was at the heart of the movement to free the slaves… If so, why didnʼt the abolitionist movement begin after the First Great Awakening? Did that movementʼs leaders, George Whitfield and Jonathan Edwards, cry out in indignation against human bondage? They did not. [Whitfield even considered slavery a blessing.] Was the anti-slavery banner raised in the colonies as a result of this re-awakening of Christian sentiment? It was not. Slavery was not eliminated in this country [nor in England, nor in France] until after secularism had attained an ideological foothold. Certainly, many of the leaders of the abolitionist movement were religious. But, although they most likely were not aware of it, they were acting on humanistic impulses [rather than on the basis of Biblical teachings].

Jon Nelson, “Christianity, Slavery, and Abolitionism” [online] The Atheist Alliance Web Center

English North Americans embraced slavery because they were Christians, not in spite of it…In the 1700s, defenders of slavery among men of the cloth were far more numerous than opponents…The involvement of northern denominations and congregations [in the anti-slavery movement] was virtually nonexistent. It is not an exaggeration to assert that the clergyman or church member who marched with the abolitionists did so in spite of his denominational connection, not because of it. The antislavery movement [in both the U.S. and in Britain] owed much of its impetus to the efforts of individuals [who were often considered radicals or fanatics by their own denominations]…Harriet Beecher Stoweʼs enormously popular anti-slavery novel, Uncle Tomʼs Cabin (1852) was written in reaction to her denominationʼs acquiescence to the practice of slavery.

Forrest G. Wood, The Arrogance of Faith: Christianity and Race in America from the Colonial Era to the Twentieth

By the mid-1800s not one of the major Christian denominations [in America] other than the Quakers held a strong anti-slavery position.

Donald B. Gibson, “Faith, Doubt and Apostasy,” Frederick Douglass: New Literary and Historical Essays, ed. Eric J. Sundquist Gibson

Now that the blight of slavery has been removed, or at least ameliorated from human society, the church predictably steps in and takes the credit. In the righteous tones of the morally duplicitous, they claim that their faith was the motivating factor, that the slave owners werenʼt “real” Christians, that the entire history of slavery only proves their contention that humans are inherently evil. Their unquestioning flocks, already convinced of Christianityʼs merits, nod their heads in obsequious agreement… Americans today view slavery as a most grievous wrong. Unfortunately, few of them recognize that the Bible they revere is at best ambiguous and at worst openly supportive of the institution.

Jon Nelson, “Christianity, Slavery, and Abolitionism” [online] The Atheist Alliance Web Center

Quakers & Unitarians (Two Sects That Other Christians Despised) As Well As Deists (Considered “Infidels”), Were The Earliest Americans Opposed To Slavery

1688—The Quakers in Pennsylvania sign an anti-slavery resolution, making them the first and only Christian denomination in the entire Western Hemisphere to make a formal protest against slavery.

1730s-1770s—Benjamin Franklin (Deist) first lets his anti-slavery views be known.

1775 (March 8)—Thomas Paine (a Deist) writes, “African Slavery in America,” published in Postscript to the Pennsylvania Journal and the Weekly Advertiser, Philadelphia, denouncing slavery and calling for its end (ones of Paineʼs earliest published writings).

1775 (Six weeks later)—The “Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery” is formed in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania by Quakers and Deists. Thomas Paine (Deist) was a founding member, and Benjamin Franklin (Deist) became its president.

1775—John Adams (Unitarian), proposes a “Declaration of Independence.” He also suggests that congress appoint Thomas Jefferson (Deist) to write the draft. Adams serves as one of the editors. A lifelong opponent of slavery, Adams did not protest when congress cut Jeffersonʼs condemnation of slavery from the Declaration. Both believed the cause of independence was more important. Adams later wrote in a letter to Timothy Pickering: “I was delighted with itʼs [the Declarationʼs] high tone and the flights of oratory with which it abounded, especially that concerning negro slavery, which, though I knew his [Jeffersonʼs] Southern brethren would never suffer to pass in Congress, I certainly never would oppose.”

1776 (January)—Thomas Paine (Deist) publishes Common Sense after which sentiment begins to build in the Continental Congress for a complete break with England.

1776 (Sept. 28)—Pennsylvania adopts a constitution. While it appears that Benjamin Franklin (Deist), as well as George Bryan and James Cannon were the principal authors of the new constitution, others such as George Clymer, Timothy Matlack and even Thomas Paine (Deist) might have been involved in its creation.

1777—Vermontʼs Constitution is composed, modeled after that of Pennsylvaniaʼs that was written by Benjamin Franklin (Deist). One of the most notable features of Vermontʼs bill of rights was the conditional abolition of slavery (the conditions were that men could be held to be a “servant, slave or apprentice” until age 21, and women until age 18).

1780 (March)—Thomas Paine (Deist) drafts and the Pennsylvania Assembly passes “The Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery”: “Every Negro and Mulatto child born within the State after the passing of the Act would be free upon reaching age twenty-eight. When released from slavery, they were to receive the same freedom, dues and other privileges such as tools of their trade,” as servants bound by indenture for four years.

1780—Massachusetts Constitution declares that all men are free and equal at birth, but it took a judicial decision in 1783 to interpret this as “abolishing slavery.”

1784 Rhode Island and Connecticut enact gradual emancipation.

1799 New York adopts gradual emancipation.

1804 New Jersey adopts gradual emancipation.

Information assembled by E.T.B. See also, “Slavery in Early America: What the Founders Wrote, Said, and Did” [online]

Thirdly, The Bible And Slavery

Throughout the Bible slavery is as cheerfully and leniently assumed as are royalty, poverty, and female submission to males. In the English Bible there is frequent mention, especially in the parables of Jesus, to “servants.” The Greek word is generally “slaves.” Jesus talks about them as coolly as we talk about our housemaids or nurses. Naturally, he would say that we must love them; we must love all men (unless they reject our religious beliefs). But there is not a syllable of condemnation of the institution of slavery.

According to Jesus “fornication” is a shuddering thing; but the slavery of fifty or sixty million human beings is not a matter for strong language. Paul approves the institution of slavery in just the same way.—He is in fact worse than Jesus. He saw slaves all over the Greco-Roman world and never said a word of protest.

Joseph McCabe, “Christianity and Slavery,” The Story of Religious Controversy, Chapter XIX

The Bible says that all the patriarchs had slaves. Abraham, “the friend of God,” and “the father of the faithful,” bought slaves from Haran (Gen. 12:50), included them in his property list (Gen. 12:16, 24:35-36), and willed them to his son Isaac (Gen. 26:13-14). What is more, Scripture says God blessed Abraham by multiplying his slaves (Gen. 24:355). In Abrahamʼs household Sarah was set over the slave, Hagar. After Hagar ran away the angel told her, “return to your mistress and submit to her.” (Gen. 16:9)

The Bible even depicts the “Lord” making his own ministers slaveholders. Numbers, chapter 31, says that the Hebrews slew all the Midianites with the exception of Midianite female virgins whom the Hebrews “kept for themselves…,” and, “the booty that remained from the spoil, which the [Hebrew] men of war had plundered included…16,000 human beings [i.e., the female virgins] from whom the Lordʼs tribute was 32 persons. And Moses gave the tribute which was the Lordʼs offering to Eleazar the priest, just as the Lord had commanded Moses… And from the sons of Israelʼs half, Moses took one out of every fifty, both of man [i.e., the female virgins] and animals, and gave them to the Levites [the priestly tribe]… just as the Lord had commanded Moses.”

At Godʼs command Joshua took slaves (Josh 9:23), as did David (1 Kings 8:2,6) and Solomon (1 Kings 9:20-21). Likewise, Job whom the Bible calls “blameless and upright,” was “a great slaveholder” (Job 1:15-17; 3:19; 4:18; 7:2; 31:13; 42:8)…Slavery is twice mentioned in the Ten Commandments (the 4th and 10th), but not as a sin. [“Thou shalt not covet thy neighborʼs wife, or his male slave, or his female slave.” Exodus 20:17]

How long must a person remain enslaved? Genesis, chapter nine, says that Noah laid a curse on one of his sonsʼ sons making him [and his childrenʼs children] “a slave of slaves… forever.” And Leviticus 25:44-46, says, “You may acquire male and female slaves from the nations that are around you. Then too, out of the sons of the sojourners who live as aliens among you… they also may become your possession. You may even bequeath them to your sons after you, to inherit as a possession forever [i.e., the slaveʼs children would be born into slavery along with their childrenʼs children, forever].” So, slaves acquired from “foreign” nations could be treated as “possessions…forever;” also, enemies taken in war. Moreover, the second Psalm in the Bible (which scholars believe was sung at the coronation of Hebrew kings) proclaims, “Ask of me [the Lord], and I shall give thee the heathen for thine inheritance [as slaves], and the uttermost parts of the earth for thy possession. Thou shalt break them with a rod of iron; thou shalt dash them in pieces like a potterʼs vessel.”

There were a few exceptions to “everlasting slavery.” If the slave was a Hebrew owned by a fellow Hebrew the master allegedly had to offer him his freedom after “seven years.” Though there is not a single penalty mentioned in the Bible should the master detain his slave longer than that period or refuse to offer him his freedom. Neither does such an offer appear to apply to female slaves. Furthermore, if a Hebrew slave chose to remain with his master after being offered his freedom, then the “Lord” told his people to “bore holes in the ears” of that slave to mark him as his masterʼs possession “forever.” So you had better speak up clearly and without hesitation the first time your master offered you your freedom because there was no Biblical provision for changing your mind at a later date. Complicating such decisions was the fact that masters often gave their slaves wives so they could produce children, yet the wife and children remained the masterʼs “possessions.” (Exodus 21:4-6)

The Bible also apparently allowed for a creditor to enslave his debtor or his debtorʼs children for the redemption of the debt (2 Kings 4:1); and children could be sold into slavery by their parents (Exodus 21:7; Isaiah 50:1). So sayeth “the word of the Lord.”

How much punishment could a master employ to discipline their slaves and ensure their obedience? The Bible tells us that a master may beat his slave within an inch of the slaveʼs life or within “a day or two” of their life: “If a man strikes his male or female slave with a rod and he dies at his hand, he shall be punished. If, however, the slave survives a day or two (before dying), no vengeance shall be taken; for the slave is his masterʼs money.” (Ex. 21:20-21) In line with such pearls of wisdom an early Christian Council, The Council of Elvira (c. 305), prescribed that any Christian mistress who beat her slave to death without premeditation was merely to be punished with five years of penance. 1 Peter 2:18-20 teaches that the Christian who is a slave should “patiently endure” even harsh unjust punishments in order to “find favor with God.”

Letʼs sum up. According to the Bible, anyone who has enough money to buy another human being is “worthy of all honor” (1 Tim. 6:1) in the eyes of the one who has been purchased. Secondly, slaves should seek to fulfill the “will of God” by obediently serving their masters (Eph. 6:5-6). Thirdly, slaves who endured “suffering” (including unjust suffering”) were “acceptable of God” (1 Peter 2:18-20). So if slaves do not find their masters “worthy of all honor,” but “disobey” their masters, and refuse to “endure sufferings” imposed by their masters, such behavior displeases not only man, but God as well. Even Jesus, in his parables, took for granted that a master had the right to discipline his disobedient slaves: “The slave who knew his masterʼs will, but did not do it, was beaten with many stripes.” (Luke 12:47)

Every book in the Bible takes the existence of slavery for granted from Genesis to Revelation. Revelation 6:15; 13:16 & 19:18 take for granted the existence of “free men” and “slaves” (verse 18:13 even takes for granted the existence of both “slaves” and “chariots,” which is odd for a book some believe to be a “vision of the future”). At any rate, it is far from clear that the Bible is “against slavery.” And thatʼs putting it mildly.

E.T.B.

Fourthly, The Civil War (Americaʼs “Holy War”)

In the United States disputes over slavery brought Presbyterians, Methodists, and Baptists to schism by 1845, and encouraged the fratricidal Civil War that finally resolved that crisis. One of the chief ironies of the conflict over slavery was the confrontation of Americaʼs largest Protestant denominations with the hitherto unthinkable idea that the Bible could be divided against itself. But divided it had been by intractable theological, political, and economic forces. Never again would the Bible completely recover its traditional authority in American culture.

Stephen A. Marini, “Slavery and the Bible,” The Oxford Guide to Ideas & Issues of the Bible, ed. by Bruce Metzger and Michael D. Coogan (Oxford University Press, 2001)

Jefferson Davis And The Southʼs View Of Slavery As Established And Sanctioned By God

Jefferson Davis, the leader of the South during the American Civil War, boasted, “It [slavery] was established by decree of Almighty God… it is sanctioned in the Bible, in both Testaments, from Genesis to Revelation… it has existed in all ages, has been found among the people of the highest civilization, and in nations of the highest proficiency in the arts… Let the gentleman go to Revelation to learn the decree of God—let him go to the Bible… I said that slavery was sanctioned in the Bible, authorized, regulated, and recognized from Genesis to Revelation…Slavery existed then in the earliest ages, and among the chosen people of God; and in Revelation we are told that it shall exist till the end of time shall come [Rev. 6:15; 13:16; 19:18]. You find it in the Old and New Testaments—in the prophecies, psalms, and the epistles of Paul; you find it recognized, sanctioned everywhere.”

- Dunbar Rowland, Jefferson Davis, Vol. 1

Davisʼs defenses of slavery are legion, as in his speech to Congress in 1848, “If slavery be a sin, it is not yours. It does not rest on your action for its origin, on your consent for its existence. It is a common law right to property in the service of man; its origin was Divine decree.” After 1856, Davis reiterated in most of his public speeches that he was “tired” of apologies for “our institution.” “African slavery, as it exists in the United States, is a moral, a social, and a political blessing.”

- William E. Dodd, Jefferson Davis

After being elected President of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis said, “My own convictions as to Negro slavery are strong. It has its evils and abuses…We recognize the Negro as God and Godʼs Book and Godʼs Laws, in nature, tell us to recognize him—our inferior, fitted expressly for servitude…You cannot transform the Negro into anything one-tenth as useful or as good as what slavery enables them to be.”

- Kenneth C. Davis, Donʼt Know Much About the Civil War: Everything You Need to Know About Americaʼs Greatest Conflict But Never Learned]

The Bible is a book in comparison with which all others in my eyes are of minor importance; and which in all my perplexities and distresses has never failed to give me light and strength.

- Robert E. Lee, Leader of the Confederate Army of the South

When the Confederate states drew up their constitution, they added something that the colonial founders had voted to leave out, namely, an invocation of the Deity. The Southʼs proud new constitution began: “We, the people…invoking the favor and guidance of Almighty God…”

- E.T.B. [See, Charles Robert Lee, Jr., The Confederate Constitutions]

Southern clergymen and politicians argued that the South was more “Christian” than the North, it was the “Redeemer Nation.”

- Charles Wilson, Baptized in Blood, 1980

With secession and the outbreak of the Civil War, Southern clergymen boldly proclaimed that the Confederacy had replaced the United States as Godʼs chosen nation.

- Mitchell Snay, Gospel of Disunion: Religion and Separatism in the Antebellum South]

Our [Christian] denominations [in the South] are few, harmonious, pretty much united among themselves [especially on the issue of slavery—E.T.B.], and pursue their avocations in humble peace…Few of the remarkable ‘isms’ of the present day have taken root among us. We have been so irreverent as to laugh at Mormonism and Millerism, which have created such [religious] commotions farther North; and modern prophets have no honor in our country. Shakers, Dunkers, Socialists, and the like, keep themselves afar off. You may attribute this to our domestic Slavery if you choose [the slaves being taught what to believe only by members of the “few, harmonious” Southern churches—E.T.B.]. I believe you would do so justly. There is no material here [in the South] for such characters [from the North] to operate upon… A people [like we Southerners] whose men are proverbially brave, intellectual and hospitable, and whose women are unaffectedly chaste, devoted to domestic life, and happy in it, can neither be degraded nor demoralized, whatever their institutions may be. My decided opinion is, that our system of Slavery contributes largely to the development and culture of these high and noble qualities.

- James Henry Hammond, South Carolinian politician, cited by Drew Gilpin Faust, ed., The Ideology of Slavery: Proslavery Thought in the Antebellum South, 1830-1860 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1981), Chapter IV, “James Henry Hammond: Letter to an English Abolitionist,” pp.180, 181, 183, 184]

A Slaveʼs View Of Slavery In The South

We have men sold to build churches, women sold to support the gospel, and babes sold to purchase Bibles for the poor heathen, all for the glory of God and the good of souls. The slave auctioneerʼs bell and the church-going bell chime in with each other, and the bitter cries of the heart-broken slave are drowned in the religious shouts of his pious master. Revivals of religion and revivals of the slave trade go hand in hand.

Were I to be again reduced to the chains of slavery, next to the enslavement, I should regard being the slave of a religious master the greatest calamity that could befall me. For of all slaveholders with whom I have ever met, religious slaveholders are the worst. I have ever found them the meanest and basest, the most cruel and cowardly, of all others.

It was my unhappy lot to belong to a religious slaveholder. He always managed to have one or more of his slaves to whip every Monday morning.

In August, 1832, my master attended a Methodist camp-meeting and there experienced religion. He prayed morning, noon, and night. He very soon distinguished himself among his brethren, and was made a class leader and exhorter.

I have seen him tie up a lame young woman, and whip her with a heavy cowskin whip upon her naked shoulders, causing the warm red blood to drip; and, in justification of the bloody deed, he would quote the passage of Scripture, “He who knoweth the masterʼs will, and doeth it not, shall be beaten with many stripes.” (Luke 12:47)

I prayed for freedom twenty years, but received no answer until I prayed with my legs.

Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave

Frederick Douglass Was Not The Only Witness To Testify That Christians Were The Cruelest Slaveholders

Henry Bibb… lists six “professors of religion” who sold him to other “professors of religion.” (One of Bibbʼs owners was a deacon in the Baptist church, who employed whips, chains, stocks, and thumbscrews to “discipline” his slaves.) Harriet Jacobs, in her narrative, informs us that her tormenting owner was the worse for being converted. Mrs. Joseph Smith, testifying before the American Freedmenʼs Inquiry Commission in 1863 tells why Christian slaveholders were the worst owners: “Well, it is something like this—the Christians will oppress you more.”

Donald B. Gibson, “Faith, Doubt and Apostasy,” Frederick Douglass: New Literary and Historical Essays, ed. Eric J. Sundquist Gibson

Letter Written By A Slave To A Minister Who Had Preached At That Slaveʼs Plantation

I want you to tell me the reason you always preach to the white folks and keep your back to us. If God sent you to preach to sinners did He direct you to keep your face to the white folks constantly? Or is it because they give you money? If this is the cause we are the very persons who labor for this money but it is handed to you by our masters. Did God tell you to make your meeting houses just large enough to hold the white folks and let the Black people stand in the sun and rain as the brooks in the field? We are charged with inattention. It is impossible for us to pay good attention with this chance. In fact, some of us scarcely think we are preached to at all. Money appears to be the object. We are carried to market and sold to the highest bidder never once inquiring whether sold to a heathen or Christian. If the question was put, “Did you sell to a Christian?” what would be the answer, “I canʼt tell what he was, he gave me my price, thatʼs all I was interested in?” Is that the way to heaven? If it is, there will be a good many who go there. If not, their chance of getting there will be bad for there can be many witnesses against them.

Blacks in Bondage: Letters of American Slaves, ed., Robert S. Starobin

It is not uncharacteristic in the study of race relations that the catechisms, as instruments of control, revealed more about the thinking of the slaveholding society and its clerical leaders than they did about the slaves.

- Forrest G. Wood, The Arrogance of Faith: Christianity and Race in America from the Colonial Era to the Twentieth

Woodʼs book explodes the myth that most slaves became Christians: figures were closer to 10%, roughly the same percentage of the free population that attended church regularly. Another false legend exposed here is that northern churches aided and encouraged efforts to free the slaves: many abolitionists broke away from the mainstream churches because they would not provide assistance to escaped slaves. Northern churches considered slavery a political issue rather than a moral one so as not to offend their southern affiliates. “Spiritual” music was anything but: Allowed to sing only religious music, slaves often composed songs that were outwardly biblical, but that were actually coded messages for the underground railroad. Subjugation of all “inferior” races was an integral part of Manifest Destiny. The author contends that since the few freethinkers were not organized, they had no say in the slavery issue. His research is incomplete: Thomas Paine almost single-handedly abolished slavery in Pennsylvania, the first state where it was outlawed, in 1780. In fact, when did the other northern churches abolish slavery? You wonʼt find that answer in this book. Most of the material deals with slavery in the United States during the antebellum period, which is probably the authorʼs special field of study. He spends only a few pages on the genocide of the Native Americans, and almost totally ignores slavery in the Spanish settlements.

- John Rush (Austin, Texas) reviewer of Woodʼs book at amazon.com

African slaves were allowed to organize churches as a surrogate for earthly freedom. White churches were organized in order to make certain that the rights of property [including the masterʼs right to own his slave] were respected and that the numerous religious taboos in the New and Old Testaments would be enforced, if necessary, by civil law.

Gore Vidal, “(The Great Unmentionable) Monotheism and its Discontents,” essay

Before the South seceded politically from the North, she seceded religiously. The three largest Christian denominations in the South, the Methodists, Baptists and Presbyterians, seceded from their northern brethren to form separate “Southern” denominations, each founded on the Biblical right (of laymen and ministers) to own slaves.

E.T.B.

The Old School (Presbyterian) General Assembly report of 1845 concluded that slavery was based on “some of the plainest declarations of the Word of God.” Those who took this position were conservative evangelicals. Among their number were the best conservative theologians and exegetes of their day, including, Robert Dabney, James Thornwell and the great Charles Hodge of Princeton—fathers of twentieth century evangelicalism and of the modern expression of the doctrine of Biblical inerrancy. No one can really appreciate how certain these evangelicals were that the Bible endorsed slavery, or of the vehemence of their argumentation unless something from their writings is read.

Kevin Giles, “The Biblical Argument for Slavery,” The Evangelical Quarterly, Vol. 66, No. 1, 1994

The Clergy Played A Pivotal Role In Promoting Secession

Southern clergymen spoke openly and enthusiastically on behalf of disunion… Denominational groups across the South officially endorsed secession and conferred blessings on the new Southern nation. Influential denominational papers from the Mississippi Baptist to the Southern Episcopalian, the Southern Presbyterian and the South Western Baptist, agreed that secession “must be effected at any cost, regardless of consequences,” and “secession was the only consistent position that Southern freemen or Christians could occupy.” (One amusing anecdote tells how a prominent member of a Southern Presbyterian church told his pastor that he would quit the church if the pastor did not pray for the Union. Unmoved by this threat, the pastor replied that “our church does not believe in praying for the dead!”)

Meanwhile, Northern clergymen blamed their Southern counterparts for “inflaming passions,” “adding a feeling of religious fanaticism” to the secessionist controversy, and also blamed them for being “the strongest obstacle in the way of preserving the Union.” In this way, the Northern clergy contributed to the belief in an irrepressible conflict, and aroused the same kind of political passions they were condemning in their Southern brethren.

One Southern sermon that had “a powerful influence in converting Southern sentiments to secession,” and which was republished in several Southern newspapers and distributed in tens of thousands of individual copies, was Reverend Benjamin B. Palmerʼs sermon, “Slavery a Divine Trust: Duty of the South to Preserve and Perpetuate It,” delivered soon after Lincolnʼs election in 1860. According to Palmer that election had brought “one issue before us” which had created a crisis that called forth the guidance of the clergy. That issue was “slavery.” Palmer insisted that “the South defended the cause of all religion and truth…We defend the cause of God and religion,” while abolitionism was “undeniably atheistic.” Palmer was incensed at the platform of Lincolnʼs political party that promised to constrain the practice of slavery within certain geographical limits instead of allowing it to expand into Americaʼs Western territories. Therefore, the South had to secede in order to protect its providential trust of slavery.

When Union armies reached Reverend Palmerʼs home state, a Union general placed a price on his head, because as some said, the Reverend had done more than “any other non-combatant in the South to promote rebellion.” Thomas R. R. Cobb, an official of the Confederate government, summed up religionʼs contribution to the fervor and ferment of those times with these words, “This revolution (the secessionist cause) has been accomplished mainly by the Churches.”

Mitchell Snay, Gospel of Disunion (See also Edward R. Crowtherʼs Southern Evangelists and the Coming of the Civil War)

The Southern Presbyterian Church resolved in 1864 (while the Civil War was still being fought): “We hesitate not to affirm that it is the peculiar mission of the Southern Church to conserve the institution of slavery, and to make it a blessing both to master and slave.” The Church also insisted that it was “unscriptural and fanatical” and “one of the most pernicious heresies of modern times” to accept the dogma that slavery was inherently sinful. At least one slave responded to such theological resolutions with one of his own: “If slavery ainʼt a sin, then nothing is.”

E.T.B.

To judge by the hundreds of sermons and specially composed church prayers that have survived on both sides, ministers were among the most fanatical of the combatants from beginning to end. The churches played a major role in dividing the nation, and it may be that the splits in the churches made a final split in the nation possible. In the North, such a charge was often willingly accepted. Granville Moddy, a Northern Methodist, boasted in 1861, “We are charged with having brought about the present contest. I believe it is true we did bring it about, and I glory in it, for it is a wreath of glory round our brow.”

Southern clergymen did not make the same boast but of all the various elements in the South they did the most to make a secessionist state of mind possible. Southern clergymen were particularly responsible for prolonging the increasingly futile struggle. Both sides claimed vast numbers of “conversions” among their troops and a tremendous increase in churchgoing and “prayerfulness” as a result of the fighting.

- Paul Johnson, A History of the American People

Other “results of the fighting” that clergymen were not nearly as boastful about included tremendous outbreaks of syphilis and gonorrhea among both northern and southern troops who took time out from their fighting and prayers to visit women who attended to the troopsʼ less than holy concerns.

- E.T.B.

The Crusades aside, Civil War armies were perhaps the most religious in history. Troops who were not especially religious prior to the war often found comfort in religion when faced with the horrific reality of combat. Those who had held strong religious beliefs before they went into battle usually found their faith strengthened. One southerner reflected that “we are feeble instruments in the hands of the Supreme Power,” while his northern counterpart believed that he was “under the same protecting aegis of the Almighty here as elsewhere…It matters not, then,” he concluded, “where I may be the God of nature extends his protecting wing over me.”

Religion, specifically the Protestant religion, went to the very heart of the American experience in the nineteenth century. Both northerners and southerners were used to expressing themselves via religious metaphors and Scriptural allusions. Once war broke out, both sides saw themselves as Christian armies, and the war itself served to reinforce this.

The Confederate soldier, in particular, was encouraged to equate the cause of the Confederacy with the cause of Christ, by the efforts of religious journals such as The Army and Navy Messenger and The Soldierʼs Friend, many of which began publication after 1863. The Messenger advised southern troops as late as 1864 that the Confederacy was “fighting not only for our country but our God. This identity inspires our hope and establishes our confidence. It has become for us a holy war, and each fearful and bloody battle an act of awful and solemn worship.” In the same year, The Soldierʼs Paper reminded its readership, “The blood of martyrs was the seed of the Church, the blood of our heroes is the seed of liberty.” According to the Mississippi Messenger, the Civil War was no more nor less than “…the ordering of Godʼs Providence, which forbids the permanent union of heterogeneous nations.” The southern soldier responded to such arguments, and took them to heart. Even after the fall of Atlanta, an artillery lieutenant from Alabama could not “believe that our Father in Heaven intends that we shall be subjugated by such a race of people as the Yankees.”

Northern soldiers too, were encouraged to find Scriptural justification for the Union cause, particularly over the matter of slavery. After Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, Julia Ward Howe composed the words to the “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” which was set to the tune of “John Brownʼs Body.” Union troops needed little encouragement to sing “Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord,” nor to reassure themselves that as Christ, “died to make men holy, let us die to make men free / While God is marching on.”

Susan-Mary Grant, “For God and Country: Why Men Joined Up For the US Civil War,” History Today, Vol. 50, No. 7, July 2000, p.24-25

Hundreds of thousands of soldiers died in the Civil War, more than the combined number of all the American soldiers who died in every other war from the Revolutionary War through two World Wars, right up to the Gulf War against Iraq. (Admittedly, diarrhea killed more Civil War soldiers than were killed in battle. But then, influenza killed more World War I soldiers than were killed in battle.) Neither is there any doubt among historians that religion played a more pervasive and intimate role in heightening disagreements and animosities during the Civil War than in those others.

E.T.B.

The Civil War as a Religious War: It can be argued that the Civil War was as much theological as it was political. The split between northern and southern churches may have precipitated political secession—once religious leaders stopped trying to work together, political leaders didnʼt bother. Ministers signed up for war in larger numbers, especially in the South. All the officers in one Texas regiment were, apparently, Methodist preachers. Religious propaganda drove war fever and inspired confidence in ultimate victory.

Ham and the Christian Defense of Slavery: The primary focus of those using Christianity to defend slavery and segregation was the story of Noah, specifically the part where his son Ham is cursed to serve his brothers. This story long functioned as a model for Christians to insist that God meant Africans to be marked as the servants of others because they are descended from Ham. Secondary was the story of the Tower of Babel as a model for Godʼs desire to separate people generally rather than have them united in common cause and purpose.

Slavery, Christian Honor, and Social Order: The concepts of honor and social order have been integral to Southern Christianity and Southern defenses of slavery. Honor meant protecting oneʼs personal image. It didnʼt matter, for example, if one was honest or dishonest, but it did matter that no one said you were dishonest. Black Africans, as descendants of Ham, were seen as lacking honor and therefore deserving of slavery. Maintaining social order meant preserving traditional structures of authority: men over women, whites over blacks.

Southern Christianity and Liberty: Southern slave owners had little interest in general liberty or maintaining a democratic republic. Their ideals were founded upon patriarchy, timocracy, and authoritarianism — not liberty, democracy, or other values people tend to take for granted today. In effect, Christianity constituted an important basis for anti-democratic movements in the South designed to deny liberty to large numbers of people, primarily (though not solely) slaves.

Christianity as a Source of Weakness in the South: Early on, Christianity was a powerful force for inspiration and national cohesion in the Confederacy. Over time, however, the quick and expected victory failed to materialize. This was a problem for both sides, but the North had a stronger nationalistic sense of self which helped see them through; the South lacked this and thus the failures on the battlefield translated into religious despair. This, in turn, sapped the Southʼs morale and prevented them from persevering.

Religious Reconstruction after the Civil War: Southerners decided that they lost because they were impure of heart rather than because slavery was an unmitigated evil — to admit that they lost because they had been wrong all along would have bee too large a blow to their sense of self and their self-identification as Southerners. They had to have been right; therefore, their loss must be attributed to other reasons. Many argued that God was chastising them in order to prepare them for some higher and more glorious purpose in the future.

Statesʼ Rights, Guilt, and Manufactured Victory: Southern secession was based upon a defense of slavery as a religious necessity and as a basic way of life. Guilt over slavery always lurked in the background, though, and losing the war made it even more difficult to face. Instead of facing it, however, Southerners claimed that they only fought for statesʼ rights and personal honor, both of which “survived.” This allowed Southern Christians to claim victory without having to deal with the moral implications of going to war over slavery.

White Supremacy and Christian Supremacy: For Southerners, maintaining separate churches was necessary to hold on to who they really were. Churches were a primary vehicle for transmitting cultural as well as religious identity. Through the churches Southerners transmitted to their children ideals about slavery, the inequality of the races, the righteousness of secession, the evil and tainted gospel preached by Northerners, and so forth. Except for the overt racism and defense of slavery, the situation today remains strikingly similar.

Christianity and the Civil Rights Movement: Although the South lost the Civil War, White Supremacy remained an important component of Christian teaching for the next century. White Christian churches taught that slavery was a just institution, as were Jim Crow laws and segregation; that white Christianity remained the last, best hope for western civilization; and that white Christians had a mandate to exercise dominion over the world — and especially the darker races who were little more than children.

Southern Christianity and Christian Nationalism in Modern America: There has been discussion of the “southernization of American society,” an argument that many basic premises and principles from Southern culture have become integrated into the rest of American culture. Included with this are appeals to racism and ethnic demagoguery, militaristic patriotism, and extreme political localism.

A parallel development, or perhaps the primary underlying development, has been the “southernization” of American Christianity. Although mainline Protestant Christianity has grown more liberal, tolerant, and open in recent decades, they have also been declining in influence. During this same time conservative evangelical and fundamentalist churches have been growing in size and power.

Christian Nationalism in America is largely a consequence of the spread of Southern Christianity. Southern Christianity has long been more conservative, evangelical, fundamentalist, militaristic, and nationalistic than churches elsewhere in the nation. As these attitudes have spread, they have transformed Christian churches that were once more liberal, especially where issues like feminism, the ordination of female clergy, and homosexuality have been concerned.

Southern Christianity holds firm to a male-dominated church situated in a male-dominated society, hyper-patriotism which is inextricably linked to traditional Christianity, hostility towards homosexuality and any divergence from traditional gender roles, opposition to sexual license and liberty, and the defense of traditional privileges for males, Christians, and at times even whites. All of this is gradually being incorporated into American Christianity generally, transforming not just American churches but also American culture and politics as well.

Austin Cline, “Christianity in the Confederate South: Southern Nationalism and Christianity”

Ed: Below Is A Copy Of The Invitation I Recʼd That Prompted My Response Above (Note: The Invitation Was Sent To Me On Request Since I Asked To Be Sent Updates From This Group, But I Suspect Many People Other Than Myself Have Received Invitations This Week To Go See This Film)

This weekend an extremely important film is opening, Amazing Grace. (If youʼre not already familiar with it, donʼt let the title throw you.)

With an excellent cast, a top-notch veteran director, and produced bt the same folks who brought us The Chronicles of Narnia, this is a film that needs to be seen. It especially needs to be seen by young people, as will become clear as the story progresses. A friend who is involved with the project told me that this is not a “feel good” movie; it is a movie that makes you want to go out and do something that makes a difference.

One Manʼs Courage and Perseverance

by Johnny Price of the Caleb Group

Two-hundred years ago this month a milestone event, in the course of a momentous campaign, took place in England. The Abolition Act of 1807 passed both the House of Lords and the House of Commons. The slave trade was abolished in Britain. However, slavery was not abolished; only the slave trade. It would be another twenty-six years before the abolition of slavery. It had taken twenty years to get rid of this nationally sanctioned, highly lucrative business enterprise.

Forty-six years. A professional lifetime. For forty-six years one man, William Wilberforce, led the fight against the trafficking of human flesh.

Since the 1600s, schooners would return from Africa with hundreds of black men and women lying on their sides in the holds of the ships, their chests pressed against the backs of those in front of them; their feet on the heads of those in the next row.

Not all who were taken from their villages would make it to the large ships; the old and sick and disabled were shot or clubbed to death. Not all who made it to the ships were immediately sent below; first the crew got their pick of the women. Then each day thereafter the lower decks were opened and the dead or nearly dead were thrown overboard. In 1783 Englandʼs high court had maintained that slaves were only “goods and chattels,” the chief justice observing that it was “exactly as if horses had been thrown overboard”.

Wilberforce, from Hull, England, elected to the House of Commons a month after turning twenty-one, had served for seven years when a combination of increasing social awareness and spiritual maturity led him to write down this realization: “God Almighty has set before me two great objects, the suppression of the Slave Trade and the reformation of manners.” These “two great objects” were inseparable, symbiotic. “The reformation of manners” (having nothing to do with how one folded oneʼs napkin) had everything to do with the moral character of the nation: a nation whose morality permitted slavery needed reformation. The existence of the slave trade was, in return, moral poison seeping continually into the hearts of the citizens.

For forty-six years, Wilberforce recruited like-minded men and women to work with him. He needed them. The opposition was fierce and came from various fronts. Some were worried about the economy; Lord Penryhn, fretted that this was a trade on which “two thirds of the commerce of this country depended”. Other members of Parliament were shocked that Christian politicians had the audacity to press for religiously based reforms in the political realm. “Things have come to a pretty pass when religion is allowed to invade private life” said Lord Melbourne.

James Boswell made his contempt known through a rather snide verse:

Go, W- with narrow skull,

Go home and preach away at Hull.

No longer in the Senate cackle

In strains that suit the tabernacle;

I hate your little wittling sneer,

Your pert and self sufficient leer.

Mischief to trade sits on your lip,

Insects will knaw the noblest ship.

Go, W-, begone for shame,

Thou dwarf with big resounding name.

Forty-six years of investigations, speeches, debates, proposals, hopeful signs, deep disappointments, partial successes, setbacks, boycotts, prayers, ridicule. Forty-six years of perseverance.

Of course people of character are multi-faceted. Their passions move them in a variety of directions, usually simultaneously. (It is those with little or no character who are shallow, one dimensional, and boring. It was Simone Weil who pointed out that only in literature are evil people really interesting.)

Wilberforce also worked for the reform of the brutal and inequitable penal system. (Crimes such as stealing rabbits and cutting down trees, whether committed by men, women or children, were punishable by hanging.) A great lover of animals he helped establish the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Until his marriage in 1797, he regularly gave away a quarter of his income to the poor. He paid the bills for people who were in prison as a result of the harsh debt laws, securing their releases. When, in 1801, the war with France and poor crops resulted in widespread hunger, Wilberforce gave away 3000 pounds more than his income.

But always at the forefront was his commitment to the abolition of slavery. For forty-six years.

On July 26, 1833, the Bill for the Abolition of Slavery passed its third reading in the House of Commons. Emancipation was finally secured. William Wilberforce was on his deathbed. When told the news he sank back on his pillow, smiled and said, “Thank God that I should live to witness a day in which England is willing to give up twenty millions sterling for the abolition of slavery!”

Three days later he died.