Billy Sunday, an orphaned bricklayerʼs son, rose to fame and wealth as an American revivalist preacher in the early 1900ʼs. Sunday preached: “I donʼt know any more about theology than a jack-rabbit knows about ping-pong, but Iʼm on my way to glory!” And, “When the word of God says one thing and scholarship says another, scholarship can go to hell!” During his career he spoke to over 100,000,000 people in the days before radios and loud-speakers; led 1,000,000 “down the sawdust trail” [i.e., converts], and he received, so it was said, millions of dollars in free-will offerings.

Sunday gradually developed a style of preaching that was as popular as it was sensational. He began by imitating those idols of Midwestern oratory, William Jennings Bryan [Christian defender of the Tennessee state law that banned the teaching of evolution in the 1920ʼs], and Robert G. Ingersoll [Americaʼs “Great Agnostic” whose speeches around the U.S. were heavily attended and reported in his day], both of whom he had heard in Chicago. He even went so far as to paraphrase the agnostic Ingersoll in a sermon titled, “The Inspiration of the Bible, or Nuts for Skeptics to Crack,” in order to prove to his audiences that a man who believed in the orthodox Protestant faith could be just as eloquent as one who flouted it. He also took some humorous anecdotes from the sermons of fellow-evangelists. And for doctrinal exegesis he borrowed freely from the sermons of D. L. Moody and T. DeWitt Talmage. The results enraptured his audiences. Some of Sundayʼs “prose poems and rhetorical gems” were compared to “the finest passages of Robert G. Ingersoll.”

Another aspect of Sundayʼs style that attracted enthusiastic response was his “power of ridicule and denunciation.” Typical was his opening-night expression: “Exercise good country cow sense and weʼll get along all right. Thereʼll be in my sermons good fodder and rock salt, barbed wire and dynamite.” With considerable relish Sunday populated hell with all the great freethinkers and “sinners” of history. The list included persons as dissimilar as Nero and Darwin, Henry VIII and Robert Ingersoll, Mme de Pompadour and John Stuart Mill, Catherine of Russia and Mary Baker Eddy. Later he even counted famed Christian preachers such as Harry Emerson Fosdick among the atheists, because they preached “Modernism” rather than Sundayʼs “Fundamentalism.”

Sunday preached that ministers who say “there isnʼt any devil—that he is a poetic personification of the sin in our natures, are calling the Holy Bible a lie!” A hundred years earlier than Sunday, in the 1830ʼs, the evangelist Charles G. Finney had written in his Memoirs about having personal encounters with the devil, who on several occasions tried to kill him, but Sunday had no such encounters.

To the evil effects of dancing Sunday devoted much of his sermon on “Amusements.” “Dancing seems to be a hugging match set to music…three-fourths of all the fallen women fell as a result of the dance.” The young ladies of 1917 were warned that “the movies are too suggestive,” that they must not “kiss or hold hands,” and that only at “the cheapskate dance halls” would you “find young girls with their dresses [up] to their shoetops!” He even opposed traditional country square dancing. “The swinging of corners in the square dance brings the position of the bodies in such attitude that it isnʼt tolerated in decent society.” Little girls were told to play dolls instead of jackstones. “We donʼt like to see girls playing leap frog,” Sunday said, “it donʼt look right.” Billiard-playing also caused him some difficulty when the YMCAʼs began to install tables: “I love the YMCA, but Iʼve never yet become reconciled to its adoption of billiard rooms.” Adolescent boys were told of the terrible consequences of masturbation.

Sunday also viewed conversion as a guarantee of inevitable success: “Following Christ you may discover a gold mine of ability that you never dreamed of possessing.” He himself had done so as a preacher, he said. If a man complained that he did his best but still did not succeed, Sunday merely answered, “You have a flaw in your character. They canʼt trust you. That is the reason you did not succeed.” Probably men who failed to become a success were not truly converted: “I never saw a Christian that was a hobo…They that trust in the Lord do not want for anything.” Of course Sunday admitted with a touch of irony, “You may not be able to be a search light or a whistle, but you can be a cog in the machine.” For the unemployed Sunday had no more sympathy than had evangelist D. L. Moody, who, during the terrible depression of the mid-1870ʼs, told an audience made up of the unemployed of Boston: “Get something to do. If it is for fifteen hours a day all the better, for while you are at work Satan does not have so much chance to tempt you…work faithfully for three dollars a week, it wonʼt be long before you have six dollars. You want to get these employers under an obligation to you…If a man works in the interest of his employer, he will be sure to keep him and treat him well.” If it was pointed out to Sunday that the unemployed were willing to work but could not get jobs [i.e., during the depression of 1914-15], Sunday resorted to the same ludicrous proposition that Moody offered in 1877, when he told the unemployed that they should return to the farm. But Sunday gave it a modern twist, “Go back to the farm and study expert dairying and help save the lives of 200,000 babies that die every year from impure milk that is sold…Go out west and study and be a horticulturist.”

Newspapers all over the nation followed the rise in Sundayʼs fame and earnings. His cumulative earnings during the years 1907 to 1918 added up to $1,140,000 [=$15,670,000 in 2003, according to an online “inflation calculator”]. . . Critics were not impressed by the fact that Sunday paid part of the salaries of his staff out of this or by the fact that he gave one-tenth of his earnings to charity. According to Rodeheaver, Sunday was a millionaire by 1920, when Dun and Bradstreet rated him as worth $1,500,000. Sundayʼs only comment was that it was nobodyʼs business how much money he had or what he did with it. Like another contemporary millionaire, John D. Rockefeller, Sr., Sunday believed that the Lord gave him his money. [Rockefellerʼs son, John D. Rockefeller Jr., at first a fan of Sundayʼs, later deserted him to take the side of Harry Emerson Fosdick, a “Modernist” rather than “Fundamentalist” Christian.]

Sunday defended the high cost of his revivals by stating that they produced more converts more cheaply than any other revivalist and even than the churches themselves. “What Iʼm paid makes it only about $2 a soul.” True enough if the expenses of the revival alone are counted. But if the free-will offering was considered part of the revival expenses, the cost of a convert would have averaged nearly $4 for the 1906-18 period. Some critics added not only the expenses and the free-will offering but money gained from sales of hymnbooks, religious pamphlets, Bibles, biographies, postcards, and other literature—plus gifts of clothes, jewelry, and bric-a-brac—all taken out of the city by the revivalist. Others noted that those who walked down front to shake Sundayʼs hand [as a sign of conversion] did not all join churches. So all in all, Sundayʼs “cost per converted soul” criterion was purely academic.

Charting membership figures of ten or twenty churches for a period of five years preceding the revivals of Billy Sunday, and five years after it (including the revival year itself)…[p.207] reveals a significant similarity of pattern…an even rate of growth in membership for the years preceding the revival, then a rapid increase in the rate of growth for the year of the revival, then a serious slump in the rate of growth (often an actual numerical decrease); and then, slowly, the growth picks up again, until, at the end of the fifth year following the revival, the rate is once more about the same as it was in the years preceding the revival. The net result in some cases is that over the ten-year period the total growth has been about the same as it would have been had there been no revival at all. . . . There is little evidence that Sunday converted many social derelicts or “booze-hoisting” bums, who were the stereotype revival converts pictured in cartoons.

Rodeheaver was Sundayʼs song leader for 20 years, who “warmed up” the revivalist crowd with “inspirational” songs before Sunday preached. Rodeheaverʼs salary reached as high as $200/week [=$2,750 in 2003], while Ackley [Sundayʼs private secretary], the next most important member of Sundayʼs revival crew, never received over $40/week [=$550 in 2003]. But in addition to their salaries they were all frequently given gifts of considerable value by grateful converts or members of the local committees with whom they worked. In addition, Rodeheaver and Ackley made money writing hymns and publishing the Billy Sunday hymnbook, Songs for Service.

The mail that Sundayʼs song leader, Rodeheaver, received during each revival campaign consisted largely of letters from lovesick women whom he had never met, and he was sued for “alleged breach of promise [to wed]” in 1914, the jury awarding the plaintiff $20,000 (=$355,000 in 2003) [p.83,269] In June, 1915, Sundayʼs private secretary, B. D. Ackley, in a fit of depression resulting from chronic alcoholism [something Sunday preached against in one of his most popular sermons, “Booze, or Get on the Water Wagon”], denounced the commercialism of the song leader, Rodeheaver, and threatened to write a series of articles exposing the whole profession of evangelism. Fred Seibert [who handled the selling of photo postcards of Sunday and various religious pamphlets at each revival] was sued for divorce in 1915. Also in 1915, suit was brought against Sundayʼs revival campaign for $1,754 [=$30,800 in 2003] worth of damage to a home they rented during a Philadelphia revival campaign, and for the destruction of wine and champagne glasses during the partyʼs occupancy.

Charges of plagiarism also hounded Sunday throughout his career. Sunday never claimed complete originality for all his sermons. “I am indebted to various friends of mine for some of my thoughts,” he would often say, “though I do not always give credit.” It became apparent, however, that, had he given credit for all the material he borrowed, there would have been little left of his own. To those who took the trouble to unearth the sermons from which he borrowed, it was evident that, while he often altered the form, the substance was the same. [p.165] Sunday claimed that he could not know the source of clippings [that he stored in envelopes according to subject category, and that he used to compose his sermons], many of which were sent to him in the mail, and he made this excuse when some freethinkers discovered he had plagiarized one of Ingersollʼs speeches. The Ingersoll borrowing was particularly damaging to Sunday for two reasons: first, because he had so consistently condemned Ingersoll to hell for his agnosticism and second, because the borrowing was absolutely verbatim.

A large part of a book that Sunday permitted to be issued under his name in 1917, called Great Love Stories of the Bible, had been ghost-written by a man named Hugh A Weir, and in 1918 Weir sued Sunday for alleged failure to live up to an agreement regarding the royalties. In 1918 another suit for plagiarism was brought against Sunday by Sidney C. Tapp.

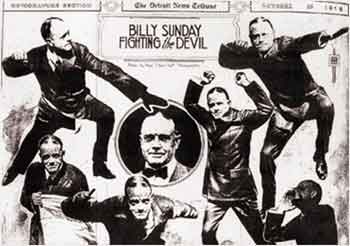

The accumulated weight of these incidents and of reiterated charges of “polite black-mail” in regard to the free-will offerings could not be shrugged off. Even the conspiratorial silence of most of the religious press regarding derogatory information could not offset the obvious failures of the revival campaigns to live up to their advance claims. A cartoon in Washington, D.C. in 1918 was indicative of the change in the publicʼs attitude. Instead of the usual picture of Sunday hurling hot shot at a cringing devil, the cartoonist portrayed a small boy clinging to his mother in the crowded tabernacle and saying, as he pointed to the men selling hymnbooks, Bibles, and authorized biographies. “Itʼs just like a circus, ainʼt it Ma?”

Sundayʼs revivalism suffered additional shocks from the bitter fight between the Fundamentalist and Modernist wings of the Protestant churches that broke out in full fury in the early 1920s. Almost every denomination was rent from top to bottom over questions of correct interpretation and proper emphasis of certain aspects of the Scriptures. Sunday, like every other evangelist, sided with the Fundamentalists, particularly on the issues of the imminent Second Coming of Christ and the literal inerrancy of the Bible. In some cities his revivals came to be looked upon as propagandistic moves by the conservatives in the battle for control of the denominations. But regardless of which side Sunday had been on, the very fact that the churches were split so deeply and so fanatically in this struggle made it virtually impossible to produce the united harmony necessary for mass revivalism.

Sunday came to consider the Southern U.S. the bastion of Christianity because, compared with other sections of the U.S., it had a higher percentage of church members, a smaller number of Catholics and foreigners, and a more rural and conservative social system. The South, he observed in one sermon, was the home of “more true-blue Americanism than any other part of the country.” But the problem of segregation he never solved; he faced it only when forced to do so by his general ostracization from the North.

Sunday claimed that Negroes and white were both equal before God, but he was unwilling to accept their equality among men. He stated his views on the Negroʼs inequality most clearly in Springfield, Illinois, in 1909, the year after the race riots there. He denounced the riots in one of his sermons and was cheered when he said that, if he had been in charge of the police during the riot, the streets would have been “crimson with the blood of the members of the gang” that had lynched the Negroes. But then he went on to state: “I am not going to plead for the social equality of the white man and the black man. I donʼt believe there is an intelligent white man who believes in social equality or an intelligent and reasonable colored man who believes in social equality. But before God and men every man stands equal whether he is white or whether he is black.” Sunday brushed aside this typical inconsistency in his next remark that he would not want his daughter to marry a Negro, and “I do not think any sensible Negro would want to marry my daughter.” He finally passed the whole question off with a bit of sophistry: “We havenʼt equality even among the white folks. Mrs. Potter Palmer gave a magnificent reception in her palatial home on Lake Shore Drive in Chicago. She didnʼt invite me.”

Firm in his belief that “only Christians should be allowed to teach in the schools,” Sunday became in the 1930ʼs a trustee of Bob Jones College, an arch-conservative Bible school that started in Cleveland, Tennessee, and later moved to Greenville, South Carolina to become Bob Jones University. [Founded by Bob Jones Sr., a Southern revivalist who accepted monetary contributions from the Ku Klux Klan (and looked the other way when they handed out leaflets of their own at his rallies), and who preached on his own college radio station, “If you are against segregation, you are against God!” It was only after the 2000 U.S. presidential election race that Bob Jones University lifted its ban on interracial dating (though students require a note from their parents to do so).] Bob Jones College was one of many such schools founded in the 1920ʼs, and 1930ʼs to take the place of those where unconverted (hence non-Christian) teachers taught evolution. “Schools,” said Sunday in 1931, “are worse than useless if they bring students under the influence of those who do not believe in Jesus Christ upon which the church and schools were built.” At Bob Jones College, Americanism of Sundayʼs variety—the variety that said, “There can be no religion that does not express itself in patriotism”— could be promoted, and the youth of America could remain free from any ideas of dissent. [Bob Jones students cheered at the news of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.ʼs assassination in the 1960ʼs, since Rev. King preached a “compromised Gospel.” And though worldwide evangelist Billy Graham had attended Bob Jones College in Tennessee for a little while before transferring to Wheaton College up north, the folks at Bob Jones College found Grahamʼs own Gospel too socially compromised since Graham worked with the World Council of Churches.]

The election of Franklin Roosevelt as president of the U.S., the repeal of Prohibition [that made it legal once again to sell alcoholic beverages], the diplomatic recognition of communist Russia, and the rise of Hitler, came as a series of shattering blows that made Sunday begin to doubt whether America could ever be saved. In one of his last sermon revisions, some time in 1934, Sunday rewrote his interpretation of the Second Coming, and entitled it “The Coming Dictator.” In this sermon he reached the ultimate stage of pessimism, and, rejecting all faith in the American heritage and destiny, he expressed his agreement with the evangelist Dwight L. Moody (founder of the Moody Bible Institute, and Moody Press) that the world was doomed. He even went beyond Moody by setting the date for the end of the world in the year 1935. “Russia has her Stalin, Italy has her Mussolini, Germany has her Hitler…and Colonel House thinks ‘even America seems ripe for one—if we havenʼt already got him [referring to the U.S. president, Roosevelt].’” He described the antichrist as “a Mussolini—a Stalin and a Hitler all rolled into one. He will give the world a ‘New Deal.’ A wizard in finance, he will stabilize the currency of the world and all industry will be brought under his control. He will issue a compulsory code for every commercial enterprise.” The similarity to U.S. president, Franklin Roosevelt, became almost too pointed, but Sunday avoided it. Sunday presented evidence to show that the era of the gentiles would end in 1935 and that the last dispensation of God “is about to close.”

In the years between 1862 and 1935, while gains from revivals and losses from declining church memberships roughly canceled each other out, the steady over-all growth in membership (although at a diminishing rate) continued. In 1936 the United States Religious Census revealed that, for the first time in history, more Americans were church members than were not. But the principal reasons for the growth of the Protestant churches in America were social rather than religious. Joining a church had become the socially respectable “thing to do;” a crisis conversion was neither necessary not expected. A watered-down version of Horace Bushnellʼs doctrine of Christian nurture had successfully replaced the ecstatic regeneration of the frontier camp meeting, and Billy Sundayʼs revivalism had played an unwitting part in the transformation. Despite his emphasis on conversion through the agency of the Holy Spirit, Sundayʼs revivalist converts were primarily expressing the acceptance of the prevailing morality. Sundayʼs revivalism made church membership a test of Americanism and salvation a ritual of acceptance of the myth. It limited membership to those whose native birth, education, occupation, and social status conformed to a strictly defined stereotype. In his fanatical self-righteousness he asserted that those who did not conform were not only damned to hell but were ineligible for citizenship or acceptance in respectable society, and his audience applauded.

The increasing discrepancy between the traditional American ideals and Sundayʼs ideals became abundantly clear in his sermons. Freedom of speech should apply to all—except to pacifists, Socialists, anarchists, communists, labor agitators, and “pinko” liberals. Freedom of religion should apply to all—except to Unitarians, Universalists, atheists, Mohammedans, Hindus, Confucianists, Mormons, Christian Scientists, theosophists, and Christian theological Modernists. All men were born equal—except Negroes and foreigners. Church and state must be separated—except that Christianity should be written into the Constitution, no Roman Catholic should be eligible for the Presidency, there should be a Bible in every schoolroom, all teachers should be converted Christians, and anything contrary to the most literal interpretation of the Bible should be prohibited by law from the curriculum of the public schools. The fact that Sunday continued to find widespread support throughout the 1920ʼs despite the reactionary extremism of his message indicates the extent to which the nation had turned aside from its principles.

Then, in 1929, a new phase began in American history. The great depression shattered the make-believe world of perpetual prosperity in the 100 percent American way. As the nation faced up to the necessity of making its business enterprise more adequately serve the general welfare, Sunday lost touch completely with the public temper. He had excluded so many from his definition of “true-blue Americans” that he found himself in a dwindling minority. He decided not only that the twentieth century had broken the speed limit but that it could never put on the brakes short of hell. At the time of his death he was ready to abandon America for heaven unless the quick advent of Christ by inaugurating the millennium, should put an end to the nation that had changed beyond recall.

His message aside, it is easy to see why those who knew Sunday liked him. As an individual he had many laudable traits. He was generous to a fault; he was courageous and honest. He was trusting to the point of naiveté yet extremely sensitive to any ridicule or rebuke. Quick to anger but equally quick to apologize, he had a keen sense of humor, a vivid imagination, a gift for words, and a positive genius for catching the eye and ear of his generation. The religious movement he led from 1908 to 1918 was not a revival in the usual sense of the word, for, on the whole, it failed to win the large numbers of new converts to Christianity which the term generally implies. If Billy Sundayʼs career was, in the long run, a failure, it was a failure shared by a generation of Americans.

Two of Sundayʼs sons took the proverbially wicked path of a ministerʼs children. His eldest son, George, attempted suicide in 1923, was arrested for auto theft and bail-jumping in 1929, was divorced by his first wife in 1930, married a Los Angeles model in 1931, and jumped from a window to his death in September, 1933. The youngest son, William A. Sunday, Jr., was divorced in 1927, remarried in 1928, and was divorced a second time on grounds of extreme cruelty in 1929. The death of Sundayʼs only daughter, Helen, in 1933, further saddened his life. He was sixty-eight in 1930, and his health failed fast in the five remaining years of his life. A heart attack in 1933 and another in May, 1935, left him seriously weakened, but he would not give up preaching. [He died of a third heart attack on Nov. 6, 1935]

Source [with edits by ETB]: William G. McLoughlin, Jr., Billy Sunday Was His Real Name (Chicago, Ill.: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1955)

No comments:

Post a Comment