Dear Victor Reppert

I enjoyed reading your discussion at your blog on moral objectivity, along with comments left by others.

Is it me, or are you asking more philosophical questions concerning moral objectivity than you have in the past? Asking questions and analyzing the answers (interminably so, especially when such questions are large overarching ones) appears to be what philosophy does best.

On the question of “moral objectivity,” I think that the most objective thing any of us can say with anything near certainty as fellow philosophical debaters is that we each like being liked and hate being hated.

We certainly like having our particular thoughts appreciated by others. And we are a bit perturbed when others donʼt “get” what weʼre saying, so we continue trying to communicate our views in ways we hope others might understand.

I also assume each of us generally prefers not having lives nor property taken from them, and generally prefer not being abused either psychologically nor physically.

I also assume that when one person has something in common with another, be it a love of a game (chess, golf, soccer), a song, the sight of a sunset/sunrise, a philosophical point of view concerning the big questions, or a religion, that liking the same thing tends to bring people together and increase their joys.

Therefore, Iʼm not sure that “objectivity” is necessarily what I am primarily after, nor what most people are primarily after.

But I will say that there is a marvelous article in this weekʼs Discover about animals with feelings. One anecdote from the article involved a magpie (freshly deceased from an accident with a car) that lay by the side of the road surrounded by four live magpies that went up and pecked gently at it, then two flew off and came back with some tufts of grass in their beaks and laid it beside the dead magpie. Then they stood beside it for a while until one by one the four magpies flew off.

This anecdote sparked my own memory of another one that I read in a turn of the century book titled Mutual Aid by the Russian evolutionist, Kropotkin (his theory of evolution emphasized the benefits of mutual aid & cooperation). Kropotkin cited Australian naturalists and farmers who observed the way parrots cooperated to denude a farmerʼs field of crops. The parrots sent out scouts, then rallied the other birds, and they would swoop down quickly and devour the crops, but sometimes some of them got shot, and rather than simply fly off altogether the birds “comrades” (remember, this is a Russian biologist speaking) would squawk in a fashion of bereavement, trying to remain as long as possible fluttering near the fallen friend and group member.

I also have read stories about the intelligence of crows, even their sense of humor. One naturalist mentioned seeing three crows on a wire, and one of them slipped, seemingly intentionally, and held himself upside down by one claw, which apparently amused the others. (Iʼd also read about experiments and anedcotes involving birds with amazing memories and vocabularies, even speaking and acting in ways one would consider appropriate for brief human-to-human exchanges.)

Elephants and llamas were some of the other animals mentioned in the Discover piece that reacted strongly to the death of members of their own species. Elephants have come back a year later to the spot where another elephant has died (as seen on Animal Planet) and they react strongly to the bones. I also recall reading in a Jan Goodall book about a young chimp (fully grown, not a baby) reacting so strongly to the death of his mother, that he simply climbed a tree and wouldnʼt come down and eat until he himself had died, apparently of grief.

The works of Frans de Waal (a famed primatologist), contain some touching stories about the compassionate behaviors of primates, notably of the most peace loving chimp species, the bonobo. When Frans took his own baby son (who was sitting in a forward facing harness strapped round Fransʼs chest) to visit some chimps at a zoo where Frans had gotten to know the chimps well, a mother chimp with her own young one saw Frans holding his baby up to the viewing glass, and the mother took her own babyʼs arms and twisted her baby around in a single movement so it was facing outward, and held her baby up to the glass so that the two babies could eye each other. Frans and the mother chimp also exchanged glances. Frans mentioned a case of a female photographing chimps on their little chimp island that had a moat around it. They were bonobos, a female dominated society, and food had just been given them, and they were portioning it out amongst themselves. The photographer wanted to get a shot but the chimps had their backs to the camera and were facing the food that had been delivered instead of facing the moat with the photographer on the other side, so the photographer started to wave her hands and scream and jump up and down to get the attention of the chimps. The other chimps looked round, except one who was suspicious and didnʼt turn around. So the female photographer continued waving her hands and shouting until finally that last female chimp turned around, and tossed the photographer a handful of food! The chimp apparently thought she was being asked to share her food! And well, she did.

In another case Iʼve read about, Washoe the chimp was on a chimp island with other chimps, one of which climbed the fence and started wadding out into the moat surrounding the island (chimps canʼt swim, they sink, their bodies are denser than human beings since they have far less body fat). This chimp started to flail around in the water, drowning. Washoe saw this, clamored over the fence, and held onto some tall grass with one hand while extending the other to the drowning chimp, who was saved.

Meanwhile Robert Hauser (Harvard prof and author of Moral Minds) has asked a lot of people a lot of tough moral questions and found out how similar their responses were across the board regardless of whether the person was religious or not.

I have responded to the question of “moral objectivity” elsewhere on Victor Reppertʼs Dangerous Idea blog, and cited statements by philosophers and primatologists from Mary Midgley to Frans de Waal to Einstein. Anyone can view my responses by clicking here and here and here and here.

Edward T. Babinski

Of course you are backtracking on moral objectivity.

ReplyDeleteYou don't have any.

are you assuming Divine Command Theory makes the most sense?

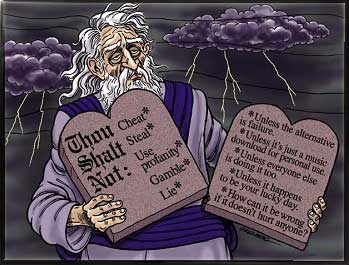

ReplyDelete"Divine command theory" was popular among many ancient Near Eastern nations who each believed their nation's high moral henotheistic god handed down divinely commanded laws to the king and people. So what? Those nations still warred against each other (just as the Christian rulers in Europe who agreed in the divine inspiration of Scripture, the Trinity and creationism, warred against each other during the Thirty Years War).

Today, invoking "divine command theory" proves nothing except the fears of Christians.

They fear that people need to be under external supernaturally revealed obligations to act morally. But it is not worth much as a proposition because it does not prove the existence of external supernaturally imposed obligations, nor prove that such obligations have been revealed nor interpreted perfectly.

In fact, even in a cosmos with the Christian God, anything can happen, and does. Some people are born with genetic predispositions, or they suffer traumatic circumstances or brain damage, or they are raised as part of a cultural or religious group that generalizes about how bad rival groups are, sometimes to the extent that outsiders are viewed as worthy of extermination -- all of which can lead to a lack of empathy and a trajectory toward psycho/socio/pathic behaviors. Divine command theory proves nothing and solves nothing.

"Divine command theory" is also prone to lead to breakdowns in society if the existence of the particular divinity or divinities (that supposedly laid down the rules) comes into question.

Makes more sense to teach kids about the generally overlapping rules of practical moral wisdom found in a wide variety of times and cultures as well as teach them to respect their ability to put themselves in place of others, using their inner recognition of shared pain receptors, shared needs and desires, and shared experiential knowledge, and knowledge of the palpable benefits of getting along. Jesus and others in the past taught to "do to others as you would want done to yourself," which implies that we each possess an inner mirror concerning what we and others prefer. Training children to rely on that inner mirror, keeping it polished, seems to make more sense than arguing over whether or not such recognitions are "divine."