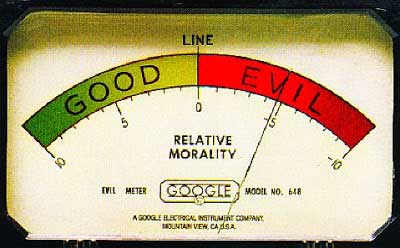

The word “objective” is overused when it comes to morality. In fact, “objective morality” seems to be one of the last bastions left to modern day defenders of classical theism. In ages past they could rely on more than just arguments for “objective morality,” because they could point to the “objective fact” of the immobility of the earth whose foundations could not be moved except by Yahweh, or they could point to the “objective fact” that the earth lay at the center of the cosmos between the underworld and heaven above, or they could point to the “objective fact” that one lone species, Homo Sapiens, was not related to any other species but created directly out of the ground by the power of Yahweh — a species that was central to His whole scheme of creation, having Adam be His gardener, followed by expulsion from the garden, then later, salvation and recreation of the heavens and the earth.

But if humans are not the only large-brained mammalian social species, if they are related to species of upright hominids with larger brains than any living primates (now extinct), and if we do not live in the center of the cosmos, nor even on a particularly stable planet, then what about human morality as well? How “objective” can it be?

I think moralizing is an imperfect process, a relative one, but not “absolutely” relative. For instance, “up and down” are not to be confused as being exactly the same direction, and we can tell the difference between things that are “higher and lower” relative to one another. We know that 99.9% of people would agree that having their lives taken from them at some other personʼs whim is less acceptable than having their belongings taken from them at some other personʼs whim, and so on down the scale. Humans are also a species like other species that is filled with numerous desires and goals, not with just one main desire and goal. Thatʼs why itʼs difficult to define “the meaning of life” for everyone. Humans will risk their lives for “causes,” almost any cause will do, from religious ones to political ones or a bevy of non-religious ones, or they will risk their lives for whatever they are attached to, be it a person, a nation, some physical object(s), to various ideas. Also, the desires and goals of the individual are constantly being tried and weighed against those of family, friends, cities in which one lives, states in which one lives, the nation in which one lives, not to mention pacts between nations, and global issues concerning the environment and economics, and any of those spheres of activity and interaction can be in conflict with one another. So, morality is an imperfect process. (There are at least eight major theories of ethics in philosophy, not to mention the questions and “ethical dilemmas” that impinge upon the legitimacy of each theory. See for instance, Eight Theories of Ethics by Gorden Graham, and, 101 Ethical Dilemmas by Martin Cohen)

Sadly, due to spheres of sometimes conflicting interest, conflicting knowledge, miscommunication and stubbornness, human beings have suffered at each othersʼ hands for as long as human beings have had hands. Throughout history and in fields of human endeavor as diverse as religion, politics, science, art, and education, great minds have suffered at the hands of little minds; great hearts and souls have suffered at the hands of the heartless and the soulless; obstinate hearts, minds and souls have suffered at the hands of equally obstinate hearts, minds and souls. Those inflicting the suffering often thought they were right to do so. And those experiencing it took succor in believing that their faith, or ideas, or actions, were right.

But on the brighter side, the vast majority of humans would sooner receive a handshake or hug than a smack in the face, would sooner have more friends than deadly enemies, would sooner have health, peace and safety than live in a world of violence where their lives or belongings are taken from them at another personʼs whim.

Christianity & “Absolute Morality”

Christianity provides its own evidence that morality is an imperfect process, as one can see when you compare the fact that nowhere in the Bible is mass murder, slavery, polygamy, concubinage, universally condemned, but each is divinely instituted and/or acceptable based on the era and circumstances.

And concerning claims of the “objectivity” of Christian morality, one canʼt help but notice how presumptuous it is to laud such “objectivity” when there remain plenty of disagreements over what a list of such “objective moral laws” might be, aside from the obvious ones that even secularists assent to like laws against murder and theft as mentioned above. The OT books of law contain plenty of divinely inspired laws but nobody but the most hard-nosed Calvinist adores them, and even then they adore them from afar, knowing that theyʼd get arrested if they starting stoning homosexuals, witches, women-not-found-to-be-virgins on their wedding nights, and disobedient children in their mid-teens. As for the NT, Jesus also left a long list of commands to his followers in his sermons, including such things as “take no thought for the morrow, or what ye shall eat or drink” “sell all you have and give it to the poor, then you will have treasure in heaven,” “give to all who ask, asking nothing in return,” “love your enemies,” but again, those are adored from afar, not to be confused with a “morally objective” list of laws to be enforced by government. This leaves us with the two millennial-old panorama of Christians disagreeing over a panoply of laws, for instance, whether or not Christians should be more pro-war or more pro-peace; disagreeing on the slavery question (no where in the Bible is slavery ever declared to be a “sin,” but slaves are to be duly disciplined, as even Jesus taught in a parable); disagreeing on what legal actions ought to be taken in cases of witchcraft, blasphemy, heresy; disagreements on whether or not one should beat oneʼs child blue with a rod and not stop for their crying—as prescribed in the Psalms; disagreeing over whether public and private school teachers should be allowed to physically discipline children; what laws should be made concerning divorce, capital punishment, etc. Even the abortion issue and end-of-life questions provoke disagreements among Christians, theologians, biblical scholars.

Further Thoughts

Thereʼs a lot people gripe about concerning human decision-making and human history. The difference between my views and those of say, a devout Christian like Augustine is that I donʼt think weʼd all be angels if “Adam hadnʼt eaten a piece of forbidden fruit,” or that “original sin” is to blame. Rather, I view the matter biologically, psychologically, and sociologically. Humans are both a social and competitive species, and thereʼs also plain old ignorance and stupidity to blame, as well as inherent difficulties in acquiring knowledge and sharing it, difficulties in learning and communicating. And there are cultural differences that include religious differences. And thereʼs the way the mind makes grandiose assumptions and generalizations, and how we learn to fear and like different things, or fear and like the same things but to different degrees.

We learn to love different things too, different holy books, different literature, different songs, and even within the writings we love thereʼs parts we may love more than others do, and other parts we may dislike more than others do. But none of us can simply turn on love and hate at will, nor can we simply turn on “belief” or “faith” at will. Itʼs all part of a process, and not an easy one. “Instant conversion” stories are far rarer than the norm of lengthy enculturation. In fact “instant conversions” involve a feeling at first, but oneʼs education in whatever religion (or lack of religion) that one has “converted to” comes later.

Michael Shermer also makes some interesting points:

I wanna believe and you do too, in fact I think belief is the natural state of things, itʼs the default option, we just believe, we believe all sorts of things. Belief is natural, while disbelief, science, skepticism is not natural. Itʼs more difficult, itʼs uncomfortable to not believe things. We have a belief engine in our brains. We are pattern seeking primates who seek associations between things. So we connect the dots, thinking A is connected to B, and sometimes it really is connected to B. We find patterns we make connections, whether itʼs Pavlovʼs dog associating the sound of a bell with food and then salivating to the sound of a bell, or a rat pressing a lever expecting food to appear. In fact it was discovered that if you put a pigeon in a box where it has to press one or two keys for a reward in the hopper box, if you start to randomly assign rewards such that there is no pattern, the pigeon will imagine there must be one, such that whatever the pigeon was doing just before the reward appeared, the pigeon will repeat that particular pattern, sometimes it was even spinning around twice counter clockwise, once clockwise, and peck the key twice. And thatʼs called superstition. [Michael Shermer, The Pattern Behind Self Deception, a TED talk, 2010]

Franz de Waal, the primatologist who has studied bonobos for decades, and written some great books, including Peacemaking Among Primates, Our Inner Ape, and Primates and Philosophers: How Morality Evolved, has some fascinating things to say:

The possibility that empathy resides in parts of the brain so ancient that we share them with rats should give pause to anyone comparing politicians with those poor, underestimated creatures.

Iʼve argued that many of what philosophers call moral sentiments can be seen in other species. In chimpanzees and other animals, you see examples of sympathy, empathy, reciprocity, a willingness to follow social rules. Dogs are a good example of a species that have and obey social rules; thatʼs why we like them so much, even though theyʼre large carnivores.

To endow animals with human emotions has long been a scientific taboo. But if we do not, we risk missing something fundamental, about both animals and us.

Review of a Book About Why We Choose The Things We Do

LET there be no mistake: nothing that you remember, think or feel is as it seems. Your memories are mere figments of your imagination and your decisions are swayed by irrational biases. Your emotions reflect the feelings of those around you as much as your own circumstances. In What Makes Your Brain Happy, David DiSalvo takes us on a whistle-stop tour of our mindʼs delusions. No aspect of daily life is left untouched: whether he is exploring job interviews, first dates or the perils of eBay, DiSalvo will change the way you think about thinking. DiSalvoʼs talk in his title of “happy brains” has little to do with joy and well-being, though. Instead, it is shorthand for our grey matterʼs tendency to choose the path of least resistance. When explaining confirmation bias, for instance, DiSalvo cites brain scans showing that we treat conflicting information as if it is a physical threat. As a result, we choose the “happier” option of ignoring details that donʼt fit our views. DiSalvo admits in his introduction that the happy brain metaphor is “intentionally oversimplified”. Indeed, by the end of the book it has been stretched dangerously thin. In a chapter on imitation, for example, he tells us that “a happy brain is happy to copy”. But an “unhappy” brain is just as big a copycat – that is how our mirror neurons work, whatever our mood. If you can ignore these glitches, What Makes Your Brain Happy is an enjoyable manual to your psyche that may change your life. As DiSalvo says: “The brain is a superb miracle of errors, and no one, except the brainless, is exempt.”

On Morality

The vast majority of us heartily dislike having our lives or belongings taken from us at someone elseʼs whim. Such “dislikes” are so universal itʼs not difficult to imagine that how “laws” originated that incorporated such “dislikes.”

Furthermore… to quote De Waal, and also Mary Midgley:

Forgiveness is not, as some people seem to believe, a mysterious and sublime idea that we owe to a few millennia of Judeo-Christianity. It did not originate in the minds of people and cannot therefore be appropriated by an ideology or a religion. The fact that monkeys, apes, and humans all engage in reconciliation behavior (stretching out a hand, smiling, kissing, embracing, and so on) means that it is probably over thirty million years old, preceding the evolutionary divergence of these primates…Reconciliation behavior [is] a shared heritage of the primate order… When social animals are involved…antagonists do more than estimate their chances of winning before they engage in a fight; they also take into account how much they need their opponent. The contested resource often is simply not worth putting a valuable relationship at risk. And if aggression does occur, both parties may hurry to repair the damage. Victory is rarely absolute among interdependent competitors, whether animal or human. [Frans De Waal, Peacemaking Among Primates]

Darwin proposed that creatures like us who, by their nature, are riven by strong emotional conflicts, and who have also the intelligence to be aware of those conflicts, absolutely need to develop a morality because they need a priority system by which to resolve them. The need for morality is a corollary of conflicts plus intellect:

Man, from the activity of his mental faculties, cannot avoid reflection… Any animal whatever, endowed with well-marked social instincts, would inevitably acquire a moral sense or conscience as soon as its intellectual powers had become as well-developed, or anything like as well-developed as in man.(Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man)

That, Darwin said, is why we have within us the rudiments of such a priority system and why we have also an intense need to develop those rudiments. We try to shape our moralities in accordance with our deepest wishes so that we can in some degree harmonize our muddled and conflict-ridden emotional constitution, thus finding ourselves a way of life that suits it so far as is possible.

These systems are, therefore, something far deeper than mere social contracts made for convenience. They are not optional. They are a profound attempt—though of course usually an unsuccessful one—to shape our conflict-ridden life in a way that gives priority to the things that we care about most.

If this is right, then we are creatures whose evolved nature absolutely requires that we develop a morality. We need it in order to find our way in the world. The idea that we could live without any distinction between right and wrong is as strange as the idea that we—being creatures subject to gravitation—could live without any idea of up and down. That at least is Darwinʼs idea and it seems to me to be one that deserves attention. [Mary Midgley, “Wickedness: An Open Debate,” The Philosopherʼs Magazine, No. 14, Spring 2001]

On Evil & God

On the question of evil, Christian theology says that everything arose directly and solely from the omnipotent power, will, intelligence and compassion of “God,” who also remains “in” all things. So what room is there for “evil” to arise? None. There should not be any “evil” if thatʼs what you believe about “God.”

Does God have free will? How can He? By definition He knows everything and only makes the perfect decision, and has all power too, so He can make sure his decisions go where He knows they must go. So God has no free will. And for that matter, neither do we, based on the above definitions of “God.”

“Free will” is not an answer. A totally “free” will is no more beneficial when it comes to making wise decisions than spinning a wheel of fortune. What we need is not “free” will but “intelligence.” We need to make intelligent decisions, not “free” ones, and for intelligent decisions we need to continue to acquire knowledge. Rather than making “free will” decisions that are allegedly “disconnected” from this space-time cosmos, we need to be connected to the cosmos through all the knowledge we can acquire and all the foresight that knowledge can give us, so that we make intelligent decisions.

Lastly, if “free will” is so important will people have it in hell, and still be able to repent? Will people in heaven have “free will” and be able to sin and get damned later?

How would you compare & contrast "objective morality" with moral realism?

ReplyDelete