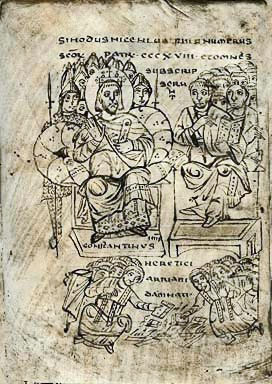

Burning of Arian books at Nicaea (illustration from a compendium of canon law, ca. 825, MS. in the Capitular Library, Vercelli) |

Churches were cleft by rivalry and schism in the days of Paul, as well as in the days of Roman persecution. Only after a Christian became Emperor did the Roman government cease persecuting Christians. But this wasnʼt good enough because Christians soon beseeched the government to settle their rivalries via Imperial decrees and coercion.

— E.T.B.

In the century opened by the Peace of the Church, more Christians died for their faith at the hands of fellow Christians than had died before in all the persecutions.

— Ramsay MacMullen, Christianity and Paganism in the Fourth to Eighth Centuries

The grateful applause of the clergy has consecrated the memory of a Christian Emperor who indulged their passions and promoted their interest. Constantine gave them security, wealth, honors, and revenge; and the support of the orthodox faith was considered as the most sacred and important duty of the civil magistrate. The “Edict of Milan,” the great charter of religious toleration, had confirmed to each individual of the Roman world the privilege of choosing and professing his own religion. But this inestimable privilege was soon violated. With the knowledge of “truth” the Emperor imbibed the maxims of persecution; and the sects that dissented from the Catholic church were afflicted and oppressed by the triumph of Christianity.

— Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Chapter 21

The privileges that have been granted in consideration of religion must benefit only the adherents of the Catholic faith. It is Our will moreover, that heretics and schismatics shall not only be alien from these privileges but shall also be bound and subjected to various compulsory public services.

— Letter of Constantine to his Vicar of the Praetorian Prefect, 326 A.D.; as cited in A New Eusebius: Documents Illustrating the History of the Church to AD 337, Ed., J. Stevenson, newly revised by W. H. C. Frend

The First Ecumenical Church Council—Held At Nicea

From the very first the Church was faced with the task of establishing dogmas. For Christianity abounds in problems more hinted at than answered in the New Testament…The first ecumenical church council, the Council of Nicea, assembled in the year 325 in the imperial palace of the first Christian emperor, Constantine. Once the discussions started the participants threw their episcopal dignity to the wind and shouted wildly at each other. They were concerned primarily with improving their positions of power.

[(Concerning such “power”) we must remember that Constantine built some impressive churches and they did not stand alone…They usually stood in a complex of buildings…that included an audience hall in which the bishop presided as judge, an extensive bishopʼs palace, warehouses for supplies for the poor, and, above all, an impressive courtyard, of the sort which stood in front of a noblemanʼs town house…Such building complexes made palpable the emergence of a new style of urban leadership…Christians themselves built countless other churches of more moderate size, that reflected the ability of the local clergy to mobilize local loyalties and to appear to local pride…Bishops and clergy received immunities from taxes and from compulsory public services. In each city, the Christian clergy became the only group that expanded rapidly, at a time when the strain of empire had brought other civic associations to a standstill. Bound by oath to “their” bishop, a whole hierarchy of priests, deacons, and minor clergy formed an ordo in miniature, as subtly graded as any town council, and as tenaciously attached to its privileges. Furthermore, Constantine expected that the bishop would act as exclusive judge and arbiter in cases between Christians, and even between Christians and non-Christians. Normal civil litigation had become prohibitively expensive. As a result, the bishop, already regarded as the God-like judge of sin among believers, rapidly became the ombudsman of an entire community. Besides this, the imperial supplies of food and clothing, granted to the clergy to distribute to the poor, turned the ferociously inward-looking care of fellow-believers for each other, which had characterized the Christian churches of an earlier age, into something like a public welfare system, designed to alleviate, and to control, the urban poor as a whole.

— Peter Brown, The Rise of Western Christendom, 2nd Ed., (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2003), p.78]

Thus at the Council of Nicea diplomacy was wielded as a weapon, and intrigues often replaced intelligence. There were so many ignorant bishops that one participant bluntly called the council “a synod of nothing but blockheads.”

[The bishops at the Council of Nicea condemned and forbade kneeling at prayer on Sundays, and also on any day between Easter and Whitsunday.]

— Walter Nigg, The Heretics

The Major Theological Debate That Took Place at the Council of Nicea

At the Council of Nicea a theological debate took place that set the stage for disputations and even riots between Christians in the following centuries. Bishop Athanasius of Alexandria defended his own teaching that Jesus was of the same exact essence (Homoousios) as the Father. Taking the other side of the debate, bishop Eusebius of Nicomedia endorsed the position of a theologian named Arius (who saw himself as defending the position of early church fathers like Origen and Tertullian, who did not speak of Jesus being of the same exact essence as the Father.) As with all theological debates, the council reached a deadlock.

It was at this point that the Emperor Constantine, who had convened the council, stepped in and sided with Athanasius. He argued that everyone present should sign the new creed that stated Jesus was of the same exact essence (Homoousios) as the Father: “Jesus Christ, the Son of God, begotten not made, by the Father as his only Son, of the same essence (Homoousios) with the Father, God of God, Light of Light.”

Constantineʼs desire to deify Jesus was not in the least surprising. It was a natural carry over from his pagan past when he had his father, Constantius, deified. It is thus natural that he would want to see the founder of his new religion put on the same pedestal as well.

Constantine added that whoever agreed to the new creed would be invited to his twentieth anniversary celebration, while those who did not agree would face immediate banishment. As a result, all but seventeen die-hard Arians signed the new creed. One can only speculate how many of the bishops signed due to Constantineʼs threat. We do know that many of the bishops who agreed initially, due to the emperorʼs threat, withdrew their agreements after returning to their own cities. Thus Eusebius, one of the signatories to the new creed, wrote (on behalf of himself and two other bishops) to Constantine upon return to Nicomedia: “We committed an impious act, O Prince, by subscribing to a blasphemy for fear of you.”

Whatever may be the reaction of the bishops who signed the formula unwillingly, the emperor was quick to act. He ordered the banishment of Arius and the burning of his writings. The leading Arian bishops were also deposed.

— “The Arian Controversy” [Online at The Rejection of Pascalʼs Wager]

“If any treatise composed by Arius should be discovered, let it be consigned to the flames, in order that no memorial of him may be by any means left. This therefore I [Constantine] decree, that if any one shall be detected in concealing a book compiled by Arius, and shall not instantly bring it forward and burn it, the penalty for this offence shall be death; for immediately after conviction the criminal shall suffer capital punishment.”

— Letter of Constantine To the Bishops and People, c. 333 A.D. in which he proscribed the works of Arius [a Christian] and in which he also proscribed the works of the pagan scholar Porphyry [who questioned Christianity], as cited in A New Eusebius: Documents Illustrating the History of the Church to AD 337, Ed., J. Stevenson, newly revised by W. H. C. Frend

The Trouble With Scripture

Both Arius and Athanasius thought the Scriptures could settle their disagreement. The Arians quoted a text from Proverbs to support their view:

The Lord created me at the beginning of his work, the first of his acts of old.

—Proverbs 8:22

To the modern scholar, the “me” refers to a pre-Christian notion of Godʼs Wisdom, but to the Arians and Athanasians alike, many Old Testamentʼs verses were interpreted as being about Jesus, and this passage, they agreed, referred to Jesus. The difference came in their interpretation of its meaning. The Arians claimed that the passage proved Jesus was created by God. But the Athanasians argued that the word “create” did not mean “coming into being.” To them the passage referred to the creation of all mankind through the resurrection of Jesus.

Another passage the Arians quoted was from the gospel of Luke, which referred to the growth of Jesus:

And Jesus increased in wisdom and stature, and in favor with God and man.

—Luke 2:52

The Arians argued, God obviously could not have “increased in wisdom and stature” for he is a perfect being. Jesus, because he could increase in wisdom and stature, could not be God. The Athanasians countered by saying that the Scriptures contain a “double account” of Jesus Christ. Some passages refer to Jesus as man, and others refer to him as God. The passage from Luke refers to the part of Jesus that is a man; so said the Athanasians.

— Wilken, The Myth of Christian Beginnings, p. 90-93

As is now widely recognized, the Scriptures and their interpretations… were the source of the “Arian controversy.”

As Robert C Gregg and Dennis E. Groh have observed, “It has been easy to overlook the degree to which appeal to the Scriptures was fundamental for Arius,” and, it might be added, the later Arians. R. P. C. Hanson in particular has said in The Search for the Christian Doctrine of God, “When arguing about the career and character of Jesus Christ himself depicted in the Gospels,” the Arians “are usually on much firmer footing than their [‘orthodox’] opponents,” in fact, “both Athanasius and Hilary are driven to take refuge in the most unconvincing arguments.” Ambroseʼs [‘orthodox’] interpretations are also, in general, “fantastic nonsense woven into purely delusive harmony.” The Arian exegesis of the first three Gospels is “confident” and “embarrassing” to their [Athanasian] opponents who treat the crucial verses in those Gospels in “uncertain” and “strained” ways. Maximinus even told the church father, Augustine, “The divine Scripture does not fare badly in our [Arian] teaching, such that it has to receive correction [Latin, ‘emendationem’] from us.”

— Kevin Madigan, “Christus Nesciens? Was Christ Ignorant of the Day of Judgment? Arian and Orthodox Interpretation of Mark 13:32 in the Ancient Latin West,” Harvard Theological Review, Vol. 96, no. 3 (2003)

“Arianism” Used To Be Just As Popular as the Doctrine that Jesus is Fully God

Arianism, which orthodox Christians now consider the archetypal heresy, was once at least as popular as the doctrine that Jesus is God… Ordinary trades people and workers felt perfectly competent—perhaps even driven—to debate abstract theological issues and to arrive at their own conclusions… Disputes among Christians, specifically arguments about the relationship of Jesus Christ the Son to God the Father, had become… intense. [p.7]

[Throughout the city everything is taken up by theological discussion: the alleyways, the marketplaces, the broad avenues and city streets; the hawkers of clothing, the moneychangers, foodsellers. If you ask for change, they philosophize about the Begotten and the Unbegotten. If you ask the price of bread, you are told, “The Father is greater and the Son inferior” If you ask, is the bath ready yet? They say “The Son was created from nothing.”

— Gregory of Nyssa, Constantinople, 381 C.E.]

The anti-Arians… demanded that Christianity be “updated” by blurring or even obliterating the long-accepted distinction between the Father and the Son. From the perspective of our time it may seem strange to think of Arian “heretics” as conservatives, but emphasizing Jesusʼs humanity and Godʼs transcendent otherness had never seemed heretical in the [eastern half of the Roman Empire]. [p.74]

The Great Council of Nicaea… was the largest gathering of Christian leaders, up to that time with 250+ bishops in attendance, almost all of them from the Eastern Empire… To some extent, this Eastern predominance can be attributed to the westernerʼs lack of interest in the Arian controversy, which still seemed to them an obscure “Greek” matter.

[The controversy over Arianism was most virulent in Greek-speaking areas, where the language lent itself to fine distinctions, and the involvement of the emperors, whose aims were usually social unity rather than theological truth, complicated matters. Often the churchmen who prevailed were those who had the emperorʼs ear. It is only with hindsight that bishops can be readily assigned to one or the other camp in the controversy: there were many gradations within the “Arianizing” outlook.—Desmond OʼGrady, Beyond the Empire: Rome and the Church from Constantine to Charlemagne (New York: Crossroad Publishing Company, 2001), p.16]

The Council of Nicaea, then, was not universal. [There were in fact over 1800 bishops in the Christian church and only 250-300 of them attended the Council of Nicea]…Several later gatherings would be more representative of the entire Church; one of them, the joint council of Rumini-Seluicie (359), was attended by more than five hundred bishops from both the East and West. If any meeting deserves the title “ecumenical,” that one seems to qualify, but its results…the adoption of an Arian creed—was later repudiated by the Church. Councils whose products were later deemed unorthodox not only lost the “ecumenical” label but virtually disappeared from official Church history. [p.74]

[After the Council of Nicaea, Constantine exiled Arian theologians.] But within three years, Arius, Eusebius, and their fellow exiles would be forgiven by Constantine and welcomed back to the Church. Eusebius would become Constantineʼs closest advisor, and would insist that Athanasius, now bishop of Alexandria, readmit Arius to communion in that city as well. A decade after that, Bishop Athanasius himself was exiled, and Arianism was well on its way to becoming the dominant theology of the Eastern Empire. [p.84]

The Council of Nicaea was the last point at which Christians with strongly opposed theological views acted civilly toward each other. When the controversy began, Arius and his opponents were inclined to treat each other as fellow Christians with mistaken ideas. Constantine hoped that his Great and Holy Council would bring the opposing sides together on the basis of a mutual recognition and correction of erroneous ideas. When these hopes were shattered and the conflict continued to spread, the adversaries were drawn to attack each other not as colleagues in error but as unrepentant sinners: corrupt, malicious, even satanic individuals. [p.84-85]

Athanasiusʼs ambition was endless; and he was very much at home in the “real” world of power relations and political skullduggery…Athanasius would soon be recognized as the anti-Ariansʼ champion. But first, he had to become bishop of Alexandria. [p.104-105]

Athanasius sent gangs of thuggish supporters into the Melitian Christian district, where they beat and wounded supporters of the Melitian leader, John Arcaph, and, according to Arcaph, burned churches, destroyed church property, imprisoned and even murdered dissident priests. [p.106]

Constantine ordered a council of bishops to meet in Tyre [concerning charges leveled against Athanasius]…Athanasius reacted with desperation…He had his agents terrorize those who might have provided evidence against him and prevented them from leaving the country…The pro-Athanasius bishops who attended the council at Tyre behaved so disruptively that the council later cited their activities as proof of Athanasiusʼs unfitness for office…The debate at the council was stormy, with many witnesses contradicting each otherʼs stories, and much name calling…After weeks of squabbling the bishops decided to send a commission to the region to interview witnesses there and the decide the truth of various accusations…The investigative commission left for Egypt… accompanied by a company of imperial troops… For the next two months Egypt was in an uproar. The Athanasians charged that the commission was obtaining evidence by means of threats and torture. The commissioners charged that Athanasiusʼs supporters were intimidating and kidnapping witnesses. By the end of the investigation it was clear that the commissionʼs report would indict Athanasius, who fled the city by night…The Bishops in Tyre condemned Athanasius for specific acts of violence and disobedience. [p.123-125]

When Constantine convened the Great Council of Nicea, he could not have imagined that the bishops would be meeting almost every year to rule on charges of criminal activity and heresy. Partisan control of these gatherings virtually guaranteed that condemned churchmen would attempt to rehabilitate themselves and punish their enemies by denying the authority of “illegitimate” councils and convening new ones. The emperor probably considered this a temporary problem. Surely, after blatant troublemakers and fanatics like Bishops Athanasius and Marcellus were removed from office, reasonable churchmen could learn to live together despite occasional differences of opinion! But this was to repeat the original mistake made at Nicea. It was to assume that doctrinal differences among Christians were not that important, that they did not reflect serious divisions of class, culture, and moral values within the community, and that they could be resolved by discovering the correct form of words. [p.133]

[More and more Christians started disavowing the “Nicene creed,” and Arianism experienced a resurgence. By the year 329 Arianism had such widespread support that Constantine became persuaded that his earlier decision was a mistaken one. In 336, the former exile, Arius, on the eve of being readmitted to membership in the church at Alexandria, was found dead on the floor beside a toilet. Poisoning is one possibility to account for the timing and manner of his passing.] However, Athanasius used Ariusʼs death as a public relations opportunity. He announced that the cityʼs prayers had been answered and “the Arian heresy was unworthy of communion with the Church.” Most telling is the language Athanasius used in describing the manner of Ariusʼs death: “Arius… urged by the necessities of nature, withdrew, and in the language of Scripture, ‘fell headlong, and burst asunder in the midst,’ being deprived of both communion and his life together.” [The Biblical reference Athanasius employed was to Judasʼs death, the apostle who betrayed Jesus, Acts 1:18] [p.137]

[Even after Ariusʼs death, Arianism remained, for there remained other more influential Christian leaders who dominated the movement.] Moreover, another death was of greater consequence than Ariusʼs. The death in question was Emperor Constantineʼs…Eusebius [an Arian Bishop] heard the Emperorʼs confession, and administered the last rites…and a decree was made that permitted all exiled bishops to return to their sees…

Athanasius [who was in exile at that time] returned to Alexandria after making a political tour of several provinces. Everywhere he rallied the anti-Arian forces and helped return exiles to power, organized opposition to “heretical” bishops, and intervened actively in local disputes. Violence dogged his steps, since both sides had organized popular support and were quite ready to use angry mobs to expel churchmen they despised or defend friendly incumbents. The result in a number of key cities was something close to civil war…Finally, Athanasius returned to Alexandria where, according to his enemies, ‘he seized the churches…by force, by murder, by war.’” [p.141-142]

Soon afterwards a large council of bishops met in Antioch [in 338] to declare that Athanasius had committed new atrocities…The leaders of the church met again in Antioch in the winter of 338-339. With the new Emperor, Constantineʼs son, Constantius [who openly embraced Arianism] in attendance, they convicted Athanasius of violence and mayhem, and ordered him deposed…Warned by his agents, Athanasius fled, and rioting and arson (which had also accompanied his return) erupted across the city… The Church of Dionysius was burned, a number of people on both sides were injured and killed, and fighting even broke out on Easter Sunday in the Church of Quirinius. Several weeks later, the mobs supporting Athanasius had been suppressed, at least for the time being.

What really happened in Alexandria during this stormy month? Athanasius in a letter charged that “Arian madmen” incited pagans, Jews, and “disorderly persons” to attack the faithful, set churches on fire, strip and rape holy virgins, murder monks, desecrate holy places, and plunder the churchesʼ treasures. He presents pictures designed to horrify and madden his readers: Jews, for example, are presented as cavorting naked in the churchesʼ baptismal waters. And, of course, he says nothing about any violence that his own supporters may have offered in his defense or in opposition to the installation of the new bishop.

Athanasius had always had a following in Alexandria, but Arius was also an Alexandrian with his share of supporters…The truth seems to be that in Alexandria and many other cities large groups of militant fighters could be mobilized by both sides, and that both sides made frequent use of them in the confused period following Constantineʼs death… What is most striking is the closeness and bitterness of the conflict in important cities like Constantinople, Antioch, Ancyra, Caesarea, Tyre, and Gaza. [p.143-144]

[Probably more Christians were slaughtered by Christians in two years [A.D. 342-343, during the Arian controversy] than by all the persecutions of Christians under the Romans during the previous three hundred years.

— Will Durant, The Story of Civilization, Vol. 4, The Age of Faith]

But what caused this deep division?…The split between Nicene and Arian Christians seems to reflect a rough division between those more in need of a powerful, just ruler and those more in need of a loving advocate and friend. Neither side in the controversy could afford to turn its back entirely on either image: the Athanasians therefore called Jesus “God from God.” And the Arians called him “a paradigm and an example.” Each side put its primary emphasis on one image while paying lip service to the other, and each side was prey to fears that the other side was aiming to obliterate “its” Jesus. While Athanasians denounced the Arians for lowering Christ to the point that his majesty and saving power would be lost, the Arians accused Athanasius and Marcellus of raising him to the point that his love (and Godʼs majesty) would be lost…

The violence in the Eastern cities ended for the time being with the forcible eviction of major anti-Arian bishops and their exile to the Western half of the Roman Empire. Many were arriving in Rome, where Athanasius had already fled. But the uncalculated efforts of these deportations would be to make the Pope of Rome a major participant in the controversy, to embroil the Western bishops, and, finally, to dive a wedge between the Christian churches of the Greek East and the Latin West [which latter would excommunicate each other]. [p.146-147]

[The Arians split into three factions: the Anomeans, the extreme party which stressed the difference between Father and Son; the Homoeans, which simply affirms that the Son is similar to the Father “in accordance with the scriptures”; and the Semi-Arians which favored the term homoiousion (Greek for “of like substance”) as expressing both the similarities and the differences between Father and Son. In 359 two simultaneous councils were held; one for the eastern bishops (in Seleucia) and one for the western bishops (in Ariminum). Both councils adopted the Homoean formula. However, this victory for Arianism frightened the Semi-Arians back into the ranks of the Athanasian fold. The death of Constantius in 361 also deprived the Arians of political support and they began to lose ground to the Athanasians.

— Livingstone, Dictionary of the Christian Church, p.33.]

[It was at this time, 361 A.D., that the Emperor Julian “the Apostate,” though raised a Christian, came to power and declared himself a pagan.] He reflected the common peopleʼs distaste for the scandalous disunity of the Church. Christianity had conspicuously failed to bring the empire together or to secure it from enemy attack. As the contemporary historian Ammianus said, “no wild beasts are such enemies to mankind as are most Christians in their deadly hatred of one another.” He deprived the Christian clergy of the special privileges [and tax exemptions] bestowed on them by his predecessors, and also took steps to re-inflame the Arian controversy by permitting Athanasius and other anti-Arians to return from exile. Violence between competing Christian groups broke out almost immediately…Bishop George of the city of Alexandria was murdered [along with several of his fellows]…by a mixed mob of pagans and anti-Arian Christians. The Bishopʼs body paraded through the streets on the back of a camel and burned. [p.195] Back around 150 A.D., Christians in Alexandria, inspired by anti-Jewish preaching, had rioted against the Jewish community. Two hundred years later those who called Jesus “Lord” were battling each other in the streets…and lynching bishops. By the time bishop George of Alexandria met his grisly death, religious riots had become commonplace throughout the region. [p.6]

[In 363, after reigning a mere three years, Julian “the Apostate” was killed in battle, after which Christian Emperors were once again the rule, one of the most intolerant of whom was Emperor Theodosius] Theodosius banned Arianism and officially declared Christianity the religion of the Roman Empire. [p.226]

In his edict of 378, Theodosius issued an order compelling all people under his rule to embrace the Catholic faith. (Codex Theodosianus XVI, I, 2) Any doctrines deviating from the Churchʼs teachings were declared criminal, those responsible for such doctrines deserving punishment.

— Gustav Mensching, Tolerance and Truth in Religion, trans., Hans-J. Klimkeit (Alabama: The University of Alabama Press, 1971), p.44.

And in 380 A.D. a decree from Theodosius read: “We shall believe in the Holy Trinity. We command that those persons who follow this rule shall embrace the name of Catholic Christians. The rest, however, whom We adjudge demented and insane, shall sustain the infamy of heretical dogmas, their meeting places shall not receive the name of churches, and they shall be smitten first by divine vengeance and secondly by the retribution of Our own initiative, which We shall assume in accordance with the divine judgment.”

— J. N. Hillgarth, The Conversion of Western Europe

Since Arianism was now identified with the “barbarians” who were its main advocates, the remaining Arians within the empire, now split into small, powerless sects, were also fair game for Christian avengers. And the struggle to uproot paganism, conducted sporadically ever since the days of Constantine the Great, now resumed in earnest.

Was the Arian controversy resolved?…Unresolved issues, appearing in changed form, continued to produce serious religious conflicts…that ended in the Great Schism separating the Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches. [p.226-227]

In the Greek-speaking lands, the end of the Arian controversy triggered more than two centuries of intense conflict [over the question of the relationship between Jesusʼs human and divine natures]. Once again, bishops met in councils to proclaim the orthodoxy of their views and to excommunicate their opponents. Once more the East knew depositions and exiles, riots and assassinations. Each side accused the other of Arianism. The Second Council of Ephesus (449) condemned the school of Antioch; the Great Council of Chalcedon (541) condemned the Alexandrians; numerous emperors intervened on one side or the other; and the controversy did not end until the one-nature “Monophysites” were driven from their own churches, many of which exist to this day.

— Richard E. Rubenstein, When Jesus Became God: The Epic Fight over Christʼs Divinity in the Last Days of Rome

It was only later agreed, by the victorious “Nicene” party, that Athanasius had been the hero of a Christian orthodoxy laid down once and for all at Nicea. But the story of Athanasius and of his defense of the “Nicene Creed” gained in the telling. It did so especially in the Latin West. By the end of the fourth century, the “Arian Controversy” was narrated in studiously confrontational terms: it was asserted that “orthodox” bishops had defeated “heretics;” and, in so doing they had offered heroic resistance to the cajolery and, at times, to the threats, of “heretical” emperors. This view of the “Arian Controversy” was constructed after the event. It contains little truth.

— Peter Brown, The Rise of Western Christendom, 2nd Ed., (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2003), p.80

Both sides of the Arian-Athanasian controversy apparently made changes to Scripture to help cement their view of the truth. See The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture: The Effect of Early Christological Controversies on the Text of the New Testament by Bart D. Ehrman (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993).

For more on the development of Christian doctrine see, The Making of Christian Doctrine, (Cambridge, 1967); The Remaking of Christian Doctrine (London, 1974); Working Papers in Doctrine (London 1976) by Maurice Wiles.

The Donatist Controversy

Donatists throughout North Africa vied with Catholics to be the major denomination… The Donatist schism had lasted almost a century, splitting the church and society and dividing families. Augustine himself had Donatist relatives. The movement, named after a bishop Donatus, had arisen out of a refusal to recognize a bishop of Carthage (Cecilian) because one of those who consecrated him had allegedly compromised his faith during Diocletianʼs persecution by offering homage [to a pagan Roman Emperor]. Eighty bishops had appealed to Emperor Constantine, who referred the matter to the church of Rome. It rejected the appeal on the grounds that a sacramentʼs validity did not depend on the celebrantʼs worthiness. But the Donatists retained a strong following for mixed religious and social motives: they claimed to be a continuation of the church of the martyrs uncompromised with the empire. The Donatists were particularly strong among the rural underprivileged, and the Berbers who did not welcome Roman suzerainty.

They considered themselves the Church of the Perfect and the Pure, who had preserved ritual purity and the Law in its entirety. Arrogantly they asked whether Catholics wanted to become Christians. One of their bishops claimed that the Donatist Church was the Ark of Noah “well tarred inside and out to keep within itself the good water of baptism and repel the world-defiling waters.” [p.72]…

North African ecclesiastical struggles were fierce: during the Donatist crisis, there was physical violence on both sides. Donatists not only whitewashed Catholic churches to purify them but killed some Catholic priests and blinded many more, using quicklime and vinegar… Squads of Donatist thugs aimed to kill a Catholic for Christ and then be killed in turn to attain martyrdom. For religious motives, they did not use swords, but had no compunction about wielding clubs or other weapons.

In 398 the most influential Donatist bishop made the fatal mistake of aligning himself with a usurper who was defeated. The religious rebels could now be considered also as traitors. From Ravenna in 405, the Catholic emperor, Honorius, issued a decree against Donatists as heretics, but was probably concerned principally, about the social disorder they fomented… Subsequent anti-Donatist rulings were extremely strict. Initially, the law decreed that the Donatist Church be disbanded: it was deprived of its bishops, its churches, and its funds while its membersʼ civic rights were restricted. Outside the city the law was not applied immediately, but laity who did not become Catholic were liable to fines. Like other North African Catholic bishops, Augustine, who hated violence, was uneasy about these measures at first but when he found coercion brought genuine conversions he justified it, adducing the biblical wedding parallel in which people were compelled to come to the banquet. He claimed that “correction” could aid the will to make a choice… He ruled out torture but, using the model of a father of a family and mindful that his hated schooldays had produced benefits later, he argued that “the rod has its own kind of charity.” [p.74]…

Augustine was endorsing coercion of those at least as numerous as Catholics who had set altar against altar, claiming to be the authentic church. Donatists were… co-religionists, not followers of other religions… Donatists and others objected that it was contrary to Christianity to impose conversion. Augustine reminded them of their violence and that they themselves had appealed to civic authorities first as well as coercing those who had broken away from Donatism. [p.75]

— Desmond OʼGrady, Beyond the Empire: Rome and the Church from Constantine to Charlemagne (New York: Crossroad Publishing Company, 2001)

The Donatist Controversy (Continued)

[Various controversial issues within Christianity] led to a schism between Donatist Christians and mainstream Christians of North Africa. Saint Augustine advocated violent suppression of the Donatists [since they wanted to “secede from the union” so to speak, to form their own “true and pure” churches]. Thus he justified massacres in the name of Christian unity. Armed [Donatist] groups, called the Circumcellions, formed to defend the “pure” [Donatist] churches, and perpetrated acts of terrorism in their name, and some committed mass suicide rather than yield to the forces [of the Christian Roman Emperors] whom they identified as “Antichrist.” The virtual civil war among North African Christians would not end until the fifth century, when invading Vandals suppressed all the churches, Donatist and orthodox alike. [p.39]

— Richard E. Rubenstein, When Jesus Became God: The Epic Fight over Christʼs Divinity in the Last Days of Rome

Increasing Persecution of Donatists

Constantine had tried persecution of the Donatists, but the sect continued to flourish and he abandoned the effort. In 398 Honorius repealed the legislation (from the short-lived pagan Emperor Julian) allowing Donatists the right of assembly, excluded them from testamentary rights, and imposed fines on them. (Clyde Pharr, trans. and ed., The Theodosian Code and Novels [Princeton Univ. Press, 1952], Book XVI, Title VI, p.464.) Augustine approved of this.

In 430 Honorius passed the death sentence on Donatists for their “criminal audacity in meeting in public.” In 413 he and Theodosius: “Anyone who baptizes someone the second time [as the Donatists were doing, baptizing people into the Donatist Christian church], he together with him who induced him to do this shall be condemned to death.” (Samuel Scott, trans. and ed. The Civil Code [Cincinnati: Central Trust, 1932], XII, 72.)

Finally in 514 Honorius threatened with death all those who dared celebrate the Donatist religious rites.

— William K. Boyd, The Ecclesiastical Edicts of the Theodosian Code [“Studies in History, Economics, and Public Law,” edited by the political science faculty of Columbia University, Vol. XXIV, Nr. 2 (New York, 1905)], p.55.

Saint Augustine on How To Treat the Donatists

“It is indeed better (as no one ever could deny) that men should be led to worship God by teaching, than that they should be driven to it by fear of punishment or pain; but it does not follow that because the former course produces the better men, therefore those who do not yield to it should be neglected. For many have found advantage (as we have proved, and are daily proving by actual experiment), in being first compelled by fear or pain, so that they might afterwards be influenced by teaching, or might follow out in act what they had already learned in word.”

—Saint Augustine, Treatise on the Correction of the Donatists

“The wounds of a friend are better than the kisses of an enemy. To love with sternness is better than to deceive with gentleness…In Luke [14:23] it is written: “Compel people to come in!” By threats of the wrath of God, the Father draws souls to his Son.”

—Saint Augustine

[Setting forth the principle of Cognite Intrare (“Compel them to enter”), a church mandate that all must become orthodox Catholic Christians, by force if necessary. Cognite Intrare would be used throughout the Middle Ages to justify the Churchʼs suppression of dissent. Walter Nigg, The Heretics: Heresy Through the Ages (1962), p.138, quoted from Helen Ellerbe, The Dark Side of Christian History, critical editing by Cliff Walker.]

Augustine was at his most disagreeably impatient when faced by groups whom he saw as self-regarding enclaves, deaf to the universal message of the Catholic Church. He insensibly presented the Church not only as the true Church, but as potentially the Church of the majority of the inhabitants of the Roman world. He was the first Christian that we know of to think consistently and in a practical manner in terms of making everyone a Christian. This was very different from claiming, as previous Christians had done, that Christianity was a universal religion in the sense that anyone in any place could, in theory at least, become a Christian. Augustine spoke of Christianity in more concrete, social terms: there was no reason why everybody in a given society (the Jews excepted) should not be a Christian. In his old age, he took for granted that the city of Hippo was, in effect, a Christian city. He saw no reason why the normal pressures by which any late Roman local community enforced conformity on its members should not be brought to bear against schismatics and heretics. He justified imperial laws that decreed the closing of temples and the exile and disendowment of rival churches [Donatist and other churches]. Pagans were told simply to “wake up” to the fact that they were a minority. They should lose no time in joining the Great Majority of the Catholic Church. In fact, the entire world had been declared, more than a millennium before by the prophets of Israel, to belong only to Christ and to his Church, and Augustine quoted the second Psalm as proof: “Ask of me, and I shall give thee the heathen for thine inheritance, and the uttermost parts of the earth for thy possession. Thou shalt break them with a rod of iron.” [Psalm 2:6,8,9,12].

[Of course not everyone was swayed by Augustineʼs arguments.] We have a recently discovered letter that Augustine wrote at the end of his life to Firmus, a notable of Carthage. Firmus had attended afternoon readings of Augustineʼs City of God. He had even read as far as book 10. He knew his Christian literature better than did his wife. Yet his wife was baptized, and Firmus was not. Augustine informed him that, compared with her, Firmus, for all his culture, even his sympathy for Christianity, stood on dangerous ground as long as he remained unbaptized.

— Peter Brown, The Rise of Western Christendom, 2nd Ed., (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2003), p.91, 92

After Donatist Christians were persecuted by anti-Donatist Christians of the Empire, leaving their fertile province pillaged with fire and sword, the Donatists welcomed the Vandal invaders of their province with joy, and North Africa was lost to Rome.

Disputes of the third and fourth general Christian councils alienated Egyptian Christians from the Christians of Asia Minor and Constantinople. The Emperor Justinian enacted measures to win back the Egyptians to orthodoxy. But that only infuriated them more, and, when the Arabs invaded Egypt the Egyptians received them as deliverers, and fell in fury on their Greek defenders, and drove them into the sea. One Egyptian Christian said to Amrou, the Saracen general, “With the Greeks I desire no communion, either in this world or the next, and I adjure forever the Byzantine tyrant, and his Christian synod of Chalcedon.”

Nestorian Christians were forced from the Empire, and went into Asia, establishing what became for a while the largest church in Christendom. “Under the rod of persecution, Nestorian and Monophysite Christians degenerated into rebels and fugitives; and the most ancient and useful allies of Rome were taught to consider the emperor not as the chief, but as the enemy of Christians.” (Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of The Roman Empire)

Differences of opinion regarding the date of Easter grew in intensity over time, and constituted a factor in bringing about the separation of the churches of Rome (Catholic) and Constantinople (Orthodox) that exists today.

Ebionite Christians and Gnostic Christians were treated poorly, although Ebionites were in all likelihood adherents of primitive Christianity, and the Gnostics were the “Christian humanists” of their day.

The hatred between Christian groups was extraordinary. In the middle of the fifth century they disputed whether the words, “who was crucified for us” should be added to the Trisagion (the “Holy, holy, holy” song sung eternally in heaven according to Isaiah and the book of Revelation). Over this dispute, the city of Constantinople suffered a series of riots … and many … Christians on the wrong side of the argument were slain.

— Madalyn Murray OʼHair, “Gibbon, the Historian, and Christianity,” An Atheist Speaks

At the church council held at Ephesus in 449 the discussion became so inflamed that the delegates went at one another with clubs, until one party held the field and could enforce the decree it desired. Fanatical bands of monks terrorized the assembly of Church notables. Envoys from the church at Rome were set upon and soundly thumped. Leo the Great called it “The Robber Council,” nor was this the only one of its kind. There were other councils at which the Church Fathers became so incensed that they hurled the Bible at each otherʼs heads.

— Walter Nigg, The Heretics

After one “election meeting” in a church, in October 366, the “ushers” picked up from the floor one hundred and sixty Christian corpses! It is sheer affectation of modern Roman Catholic writers to question this, as we learn it from a report to the emperor of two priests of the time. The riots of the Christians that filled the streets of Rome with blood for a week, are, in fact, ironically recorded by the contemporary Roman writer, Ammianus Marcellinus.

In one day the Christians murdered more of their brethren than the pagans can be positively proved to have martyred in three centuries, and the total number of the slain during the fight for the papal chair (in which the supporters of Pope Damasus literally cut his way, with swords and axes, to the papal chair through the supporters of the rival candidate Ursicinus) is probably as great as the total number of actual martyrs. If we add to these the number of the slain in the fights of the Arians and Athanasians in the east and the fights of Catholics and Donatists in Africa, we get a sum of “martyrs” many times as large as the genuine victims of Roman law; and we should still have to add the massacre by Theodosius at Thessalonica, the massacre of a regiment of Arian soldiers, the lives sacrificed under Constantius, Valentinian, etc.

This frightful and sordid temper of the new Christendom is luridly exhibited in the murder of Hypatia of Alexandria in 415. Under the “great” Father of the Church, Cyril of Alexandria, a Christian mob, led by a minor cleric of the church, stripped Hypatia naked and gashed her with oyster shells until she died [though I have read that she was clubbed to death before her flesh was stripped off her bones—E.T.B.]. She was a teacher of mathematics and philosophy, a person of the highest ideals and character. This barbaric fury raged from Rome to Alexandria and Antioch, and degraded the cities with spectacles that paganism had never witnessed.

Salvianus, a priest of Marseilles of the fifth century, deplores the vanished virtue of the pagan world and declares that “The whole body of Christians is a sink of iniquity.” “Very few,” he says, “avoid evil.” He challenges his readers: “How many in the Church will you find that are not drunkards or adulterers, or fornicators, or gamblers, or robbers, or murderers—or all together?” (De Gubernatione Dei, III, 9) Gregory of Tours, in the next century, gives, incredible as it may seem, an even darker picture of the Christian world, over part of which he presides. You cannot read these truths, unless you can read bad Latin, because they are never translated. It is the flowers, the rare examples of virtue, the untruths of Eusebius and the Martyrologies, that are translated. It is the legends of St. Agnes and St. Catherine, the heroic fictions of St. Lawrence and St. Sebastian that you read. But there were ten vices for every virtue, ten lies for every truth, a hundred murders for every genuine martyrdom.

— Joseph McCabe, How Christianity Triumphed