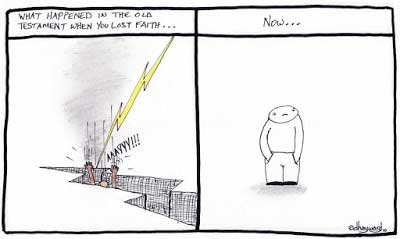

Why were some of Jesusʼs most spectacular nature miracles only seen by a few (unlike Mosesʼ alleged miracle of dividing an entire sea which would have been viewed by the multitudes)? Jesusʼs nature miracles include the stilling of the storm and the walking on water allegedly seen only by some people in a boat. While only three apostles apparently saw Jesusʼs transfiguration on an unidentified “mountain.” Quite a miracle, Jesus shining bright as the sun and speaking with Moses and Elijah. But only for the eyes of three people? And Jesus told them to “tell no one” about it until later? (That might just be a convenient excuse for how and why such a tale arose later among some Christians.)

As for the miracle of the feeding of the multitude, I doubt that large groups of people would go out to the “wilderness” (an unidentified “wilderness” in the first two Gospels) to hear either the Baptist or Jesus speak without also taking some food like bread or dried fish. Thereʼs also no indication in the earliest telling of the story in Mark that anyone saw a miracle taking place, nobody says anything about being awestruck, nor is any miracle described such as extra fish appearing out of thin air or the flesh on the fish being instantly replaced as soon as one piece was torn off. The apostles also are depicted a little later as still worrying over where their next meal was going to come from, and rebuked for not understanding concerning the multitude being fed. But instead of Jesus mentioning how they saw fish coming out of thin air, or any other miracle they allegedly would have seen taking place, he points them to the baskets of leftovers. By the time of the fourth Gospel the people do proclaim it as a miracle taking place, but still no description as to how it occurred, and in the fourth Gospel it is Jesus himself handing out the food.

Why did the three towns in Galilee in which Jesus performed most of his Gospel miracles reject him? Jesus allegedly performed most of his miracles in or around those three towns, what scholars call “the Evangelical Triangle” (Chorazin, Bethsaida, Capernaum), and Jesus says those towns will be judged more than Sodom and Gomorrah for having rejected him. Also, there is no record of Jesus performing miracles in large cities in the same region such as Sepphoris which was located near Nazareth, nor did he perform miracles in other large cities like Caesarea Philippi, Tiberius, Hippos (the last two being on the shores of the Lake of Galilee), nor any miracles performed in the large city of his final destination, Jerusalem, at least none that the earliest Gospels mentions, aside from the resurrection which in Mark is merely an empty tomb tale, because no one sees the miracle of Jesus exiting the tomb, and the young man in the tomb says “He has gone before you to Galilee, there you will see him.” In other words the earliest Gospel has the risen Jesus not appearing in Jerusalem at all.

The Lukan version is different from Mark or Matthewʼs in that the message at the tomb has undergone changes so that it no longer says Jesus has gone on before them to Galilee to be seen there. Instead, the message at the tomb is simply, “Remember when Jesus spoke to you in Galilee saying he would be resurrected?” So thereʼs no longer anything about Jesus going before them to Galilee to be seen there. Instead, Jesus appears in Luke and tells them to “remain in Jerusalem.” And he demonstrates he is not a spirit at all, but has flesh and bone, and escorts them (in a non-spirit but bodily state) out of Jerusalem, through the streets all the way to Bethany, “he led them to Bethany.” Imagine being escorted by a flesh and bone resurrected Jesus out of the city of Jerusalem, through its streets, and to a nearby city, but no Hosannas, no cries of He is risen! No knocking on Pilateʼs or Ciaphasʼs doors. Itʼs like Jesus tiptoed with his apostles out of the big city.

Even the story of the “empty tomb” is acknowledged by Evangelicals like Michael Licona to be questioned by many historical Jesus scholars because in its earliest telling in the Gospel of Mark that Gospel ends with women fleeing the empty tomb and “telling no one” what they saw. The Greek is very emphatic involving the doubling of a word for emphasis, hence they did not tell anyone anything. But if literally no one was told such a tale then we do not know when the tale about an “empty tomb” first began to circulate. Nor do the women in Mark, the earliest Gospel, meet a raised Jesus along the way as in later written Gospels.

In light of the above questions what are we expected to believe? Has God ensured we are reading historically authentic stories in the Gospels?

Nor does anyone with such questions have to claim that everyoneʼs personal religious or supernatural experiences are false in order to ask the question, How can God expect us to know what to make of such a diversity of miracle stories, visions and NDEʼs from people around the world with different beliefs? They represent quiet a mixed bag of evidence, see here.

And comparing the Gospels with say, the works of an ancient historian like Herodotus, please note:

- Herodotus challenges conventional legend; the gospels make no challenges.

- Herodotus names sources; the gospels do not.

- Herodotus weighs evidence; gospels do not.

- Event in Herodotusʼs city; Gospel accounts not in authorʼs city.

- Herodotus consciously wrote history; Markʼs Gospel is more akin to a hagiographic bios.

The Gospels plainly do not equal elite and historiographical biographies of the Roman era.

Unlike the Gospels, elite historiographical biographies “are much more prone to cite their sources, include discussion of eyewitness experiences, use direct speech and dramatic dialogue sparingly, utilize far more subordinating as opposed to coordinating conjunctions, apply more diegetic as opposed to mimetic narrative techniques, and exercise more authorial control in not borrowing large amounts material from earlier texts than what is seen in the canonical Gospels. In contrast, popular–novelistic biographies, seldom discuss their literary or historical sources, contain little overt discussion of eyewitness experiences, are replete with direct speech and dramatic dialogues, utilize parataxis and coordinating conjunctions far more often, apply more mimetic as opposed to diegetic narrative techniques, and are written highly anonymously in borrowing large amounts of material from earlier narratives, as ʻopen texts.ʼ As such, on the broad spectrum of ancient biography, I think that the Gospels far more resemble popular and novelistic biographies than they do elite and historiographical biographies”

The above quotation is from Matthew Fergusson whose Master´s thesis was on Seutonius´ biographies of the Roman Emperors and who is working on a Ph.D. thesis related to obvious distinctions between the Gospels and elite historiographical biographies of the Roman era. See also his online piece that delves deeper into such distinctions, Ancient Historical Writing Compared to the Gospels of the New Testament, and his posts on Ancient Biography.

And speaking of crucial writings we lack from the first century…

We do not have anything written directly by Jesus himself or any of his original disciples (I think even Michael Licona admits that the evidence that Jesusʼs earliest apostles penned any of the Gospels remains questionable, nor have Bauckhamʼs arguments for apostolic authorship based on “inclusio” taken the scholarly world by storm. His scholarly reviewers have pointed out all the questions he is still begging).

Nor do we have any written responses to Jesus from the Pharisees, Sadducees, scribes, or teachers of the law. Nor any from Ananias, Caiaphas, Herod or Pilate about the events we find in the gospels.(The absence of such writings even led to some early Christians forging a document titled The Gospel of Nicodemus, featuring the Acts of Pilate!)

Nor do we have a single casual letter from anyone mentioning their first hand experience of having gone to see and hear Jesus of Nazareth.

Nor do we have anything written by the Apostle Paul before he converted telling us about the church he was persecuting.

Jesus always had the last word over his opponents in the gospel accounts. His victory in debate is assured since his followers are writing such tales, like when Plato wrote Socratesʼ dialogues. But genuine debates in religion usually do not end so neatly with the opposite side having no further reply. It would be nice to know what his first century opponents said in response to Jesus, in their own words.

The Jews of Jesusʼs day believed in Yahweh and that he does miracles, and they knew their Old Testament prophecies, and yet an overwhelming number of them did not believe Jesus was the Messiah or anointed one, nor that he was raised from the dead by Yahweh. So Christianity didnʼt take by storm the very land where Jesus was seen and heard directly by people, but instead it had to reach out to the Greco-Roman world for converts. Even Paulʼs missions to Jews in the Greco-Roman world didnʼt raise as many converts as among Hellenists. So why should we believe if many of his fellow Jews who saw Jesus and heard him preach didnʼt? The city of Jerusalem was not converted. Christianity remained a small Jewish sect, one of many, until such tales reached the ears of Greco-Romans.

There are other things we donʼt have but would like to. We donʼt have the correspondence from Chloeʼs household in Corinth (1 Corinthians 1:11) telling us of their church disputes, especially concerning the resurrection that Paul responded to. Nor do we have their response to Paulʼs first letter which forced him to defend his apostleship, since they questioned it afterward (2 Corinthians). Nor do we know what Paul meant when he said some of the Corinthians and Galatians had accepted a “Jesus other than the Jesus we preached” (2 Corinthians 11:3-4) or a “different gospel” (Galatians 1:6-8). What we do know is that the sectarian side that wins a debate writes the history of that debate and chooses which books to include in their sacred writings. We donʼt even have one legitimate Old Testament prophecy that specifically refers to Jesusʼs resurrection. Nor do we have any convincing present day confirmations that God works miracles like virgin births, resurrections (or ascensions into heaven) in todayʼs world, something that would be of critical importance to historians when assessing these claims.

What we have at best are second-hand or more testimonies filtered through the gospel writers. With the possible exception of Paul who claimed to have experienced the resurrected Jesus in what is surely a visionary experience (so we read in Acts 26:19, cf. II Cor. 12:1-6; Rev. 1:10-3:21—although he didnʼt actually see Jesus, Acts 9:4-8; 22:7-11; 26:13-14), everything else we are told comes second hand.

And considering WHAT WRITINGS WE DO POSSESS (dare I saw what “God” has preserved for us) FROM THE FIRST CENTURY (as if God could not preserve writings any more confounding for your average Christian apologist), those INCLUDE the Dead Sea Scrolls which raise questions as to orthodox Christian interpretations of Jesusʼs motivation and mission, since the Dead Sea Scrolls composed by that scribal community prove they were a community of apocalyptic cultists preparing for the worldʼs final judgment. The Dead Sea Scrolls include OT writings, but also inter-testamental writings like the book of Enoch, as well as books written by the scroll community such as the Book of the Wars of Sons of Light and Darkness (about the worldʼs final battle and supernatural judgment), the Melchizadek Scroll (about a divinely appointed figure that would appear in the heavens soon to judge the earth), and commentaries on OT writings in which the members of that community found clues to the soon coming final judgment. Even their community laws and ascetic practices were meant to keep them pure in preparation for the soon coming supernatural judgment of the people of earth, which only adds credence to the view that Jesus of Nazareth may very well have been the leader of an apocalyptic movement with similar failed expectations.

Are there major miracle-working prophets like Moses, Elijah, Elisha, or Jesus today?

Wouldnʼt you agree itʼs been two thousand years since the last one? And wouldnʼt you agree that the time was far shorter from Moses to Elijah/Elisha, as well from Elijah/Elisha to Jesus, when compared with the long length of time from Jesus until today? And still no major miracle-working prophet of their stature has arrived to further expound or clarify Godʼs words for us with authority and power? Nor does it increase my confidence that the time between the writing of the last book of the Old Testament and the first book of the New Testament was merely a century or two while it has been almost two thousand years since the last book of the New Testament was written with no additional canonical words of God, no definitive words clarifying the older words either, just endless rival interpretations lying along a spectrum of conservative-moderate-liberal.

- Why did Jesus only appear to “brethren” instead of everyone?

- Why donʼt we have any of the “brethrenʼs” first hand accounts of such appearances?

- The only first-hand words concerning an appearance of Jesus are found in Paulʼs letters, and those words are very few, namely, “He appeared to me,” and if Luke-Acts is correct that Jesusʼs resurrected body rose up to heaven before Paulʼs day, then Paul did not encounter a bodily resurrected Jesus.

- Nor does Paulʼs view of the resurrection in his letters appear to be the same as that of later NT writers, click here and read the last half of the piece.

On Paulʼs Conversion & Personality

The tale in Acts that depicts Paulʼs conversion is later than Paulʼs letters, and even if there is some truth in it it looks like a case of “snapping,” a phenomenon that psychologists have observed in others who have undergone radical reversals in beliefs and behavior, even in our own day, click here.

Additional explanations can also be found:

Zeba A. Cookʼs Reconceptualising Conversion: Patronage, Loyalty, And Conversion In The Religions Of The Ancient Mediterranean, shows that Paulʼs case was not unique. It followed a pattern found everywhere in the Mediterranean, click here for more details.

Neil Elliotʼs chapter, “The Apostle Paul and Empire,” includes a sub-section on “The Politics of Paulʼs ‘Conversion’” he explains Paulʼs transition from persecutor to apostle in light of the tense political situation in Judea coupled with Jewish hopes of Godʼs intervention. Elliot discusses the highly charged atmosphere of Rome's challenge to Judaism and Judaism's resistance. One might add that prior to joining the Christian movement Paul may have viewed the need for Judaism to maintain a united front against Roman pressures aimed at his Jewish faith and practice. He might have even feared that the spread of Christianity among the Jews could be used as an excuse by Rome to increase pressures on Jews/Judaism of all types. On the other hand, Paul would not merely have been repulsed by Christianity, but also attracted by their predictions of a soon coming kingdom of God that would soon replace Rome. Such a belief would have resonated with Paulʼs own hopes, and we see in Paul's early letters his own predictions of a soon coming Lord who would set up a new kingdom on earth. Paulʼs attempt to stall Roman persecution of his people by persecuting Jewish Christians who preached a soon coming kingdom of God to replace Rome would have appealed to Paulʼs own hopes. Elliotʼs chapter appears in In the Shadow of Empire: Reclaiming the Bible as a History of Faithful Resistance. Also see Apocalypse Against Empire: Theologies of Resistance. Reading Paulʼs letters Elliott points out the ways in which Paul depicted himself as a diplomatic herald speaking in the name of an approaching conqueror (Caesar was also regularly hailed as a kyrios), preparing the cities of a province for a coming change of regime. One also canʼt help but note Paulʼs false predictions that the Lord was coming to judge the world soon, and how happy the thought made Paul.

The conversion tale of Paul in the later written Book of Acts could be fabricated to some degree, a Christian urban legend, since it reflects earlier tales like Euripidesʼ play The Bacchae (where the persecutor Pentheus is ironically converted despite himself to the faith of Dionysus by an unwelcome personal epiphany of that god) and 2 Maccabees 3 (where Heliodorus, agent of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, is prevented from robbing the Jerusalem temple by a vision of angels, whereupon he is blinded, miraculously cured, and converts to the true faith).

Further questions arise as to Paulʼs veracity when you note the way his words and actions both before and after his conversion constitute those of a single-minded and controlling individual, passionate to a fanatical degree, click here.

Further Questions

After Jesus “appeared” to his apostles why didnʼt he show himself to Pilate, the soldiers who crucified him, the crowds who cried for him to be crucified, etc., and speak to them some words of forgiveness and hope? If they tried to crucify him again, he could demonstrate that that was impossible now. He could even transfigure in front of them. Or rise up into the air in full view of a city full of people. Or even descend from the sky above Rome and be seen by many who would probably rush to see where heʼd landed, and then preach there.

Because God concentrated so many of his prophets and miracle workers in a small circle of the ancient Near East it took 1400 years before Christians reached the New World and began preaching the Gospel there, and longer still to reach Japan, Australia, the far northern and southern hemispheres. Speaking of waiting…

Acts says the apostles waited seven weeks before preaching that Jesus was raised. Why wait seven weeks if “many risen saints” had climbed out of their opened graves (per Matt) right after Jesusʼs resurrection and “showed themselves to many in the holy city” (presumably Jerusalem)?

Why did the resurrected Jesus have to leave the earth? Couldnʼt he remain on earth, traveling, preaching, teaching, or return from time to time to correct misinterpretations of his words or prevent schisms? Or prevent the founding of rival religions like Islam? After all, in the fourth Gospel it was Jesusʼs fervent prayer that his followers would remain as one in perfect unity as evidence of the truth, the implication being that without perfect unity the truth comes into question, just as it has. Even with the Holy Spirit allegedly leading Christians into truth as promised in a NT letter the history of Christianity consists of disagreements, heresy-hunts, and schisms too numerous to mention.

(Some apologists reply that Jesus had to leave the earth before the Holy Spirit could be sent, but according to the earliest two Gospels the Holy Spirit could descend like a dove to earth even when Jesus was still there. Also after the Holy Spirit was sent, Jesus could still pop down and appear to Paul. So why has Jesus popped down so infrequently since then?)

Comparing the Gospel of John with the Synoptics

Comparing the Gospel of John with the three synoptic Gospels, Mark, Matthew and Luke, increases suspicions that stories may have grown and changed over time. Biblical scholars agree in viewing the sayings of Jesus in the fourth Gospel (the Gospel of John) with greater suspicion than sayings in the earlier three Gospels. Even Christian apologists for an inerrant Bible admit that Jesusʼs words in the fourth Gospel may not be historically authentic, but more like the spirit of what Jesus meant. Why? Because…

- The Gospel of John, starts with the authorʼs claims ABOUT Jesus. Its lengthy theological introduction contains the words and praises of the author, not Jesus. And you find words and phrases similar to the authorʼs put into the mouths of John the Baptist and Jesus in the first few chapters. Not high evidence favoring their authenticity. More likely the authorʼs own creation, including the dialogues of the Baptist and Jesus in chapters 2-3.

- Scholars suspect that Jesus never said “Ye must be born again,” and with plenty of good reasons for doing so. See here.

- The story of the anointing of Jesus by Mary, sister of Lazarus, as well as the tale of Lazarusʼ resurrection are tales that seem to have arisen via combining earlier Gospel tales about individual women who anointed Jesus, where they lived, how they anointed Jesus, and then adding a figure from a Lukan parable, a beggar, named “Lazarus,” turning him into a wealthy person with “two sisters” (taken from Luke who never mentions “Lazarus” as an historical person). You can easily see how the fourth Gospel writer could have plucked all the information for his tale from Mark and Luke, reusing information from their Gospels to create a new tale about Jesus, indeed a new marvelous miracle never heard before. See here.

- Nor does the Gospel of John hesitate to have plenty of characters recognize Jesus as the Messiah right in its first chapter. Compare the synoptic gospels, especially in Mark (1:11, 25, 34, 441 9:9, etc.), where Jesus refrains from announcing his Messiahship in public, and Peter is the lone apostle to mention it out loud, and only later in the story. In fact in Matthew multitudes hail Jesus merely as a prophet (Matthew 21:10). But in GJohn Jesus is recognized by his disciples as the Messiah right in chapter one as soon as they hear about him, and the Baptist declares Jesusʼs whole mission in a nutshell, “the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world” from the very beginning of his ministry. Jesus spends all of his other discourses talking about himself (John 1:16,29-34,41,45,49,51; 2:11,18; 3:13-30; 4:25-26,42; 5:18-47; 6:25-69; 7:28-29; 9:37; 10:25-26,30-36). He doesnʼt teach the people in parables about the kingdom of God, heʼs constantly talking about himself.

- Note also how Matthew 11:2-6 and Luke 7:18-23 agree that John the Baptist wavers in faith in Jesus as Messiah; but in the Fourth Gospel (1:16, 29-34 and 3:27-30) thereʼs no mention of such wavering. John the Baptist recognizes Jesus as Messiah from first to last—even calling him “The Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world” soon after his baptism.

- The Synoptics date Jesusʼs crucifixion on the day of the Passover (Matthew 26:171 Mark 14:12, Luke 22:7), whereas John places it on the day before the Passover, and at a different hour of the day (John 13:1,29; 18:28; 19:14,31,42). Scholars suspect that the reason for changing the day and hour of Jesusʼs death in the last written Gospel was to suit the theological notion of its author that Jesus was “The Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world,” putting such an announcement into the mouth of John the Baptist—and wishing to bring it up again at the moment of Jesusʼs death. Therefore he altered Jesusʼs day and hour of execution so it would coincide with the day and hour the “Passover lambs” were being slain. (Unfortunately, having altered the day (and hour) to try and make a theological point, the Johnnine author never concerned himself with the fact that Passover lambs were not slain for “sin.” The animal in the Hebrew Bible that did have the “sins of the people” placed on it was not a lamb at all, but a goat—neither was the goat slain but kept alive in order to carry away the sins of the people into the wilderness, i.e., the “scape goat.”)

- And though the account of Jesusʼs baptism in one of the earlier Gospels, Mark 1:9 (cf. 1:4 and 10:18), leaves open the suspicion that John the Baptist was greater than Jesus and that Jesus was sinful, the fourth Gospel (John 1:29-34 and 3:26) eliminates such suspicions.

- Jesusʼs concern for Israel as depicted in the earlier gospel, Matthew 10:5-6 and 15:24 is unknown to the Jesus in John 5:45-471 8:31-47. Instead, more than sixty times the word(s) “Jews” and/or “The Jews,” are used in GJohn to depict Jesusʼs enemies, even by Jesus himself. (Since Jesus himself was a “Jew” the repeated use of such a broad term makes greater sense if it was not spoken by the historical Jesus, but was a phrase that began cropping up more often after a rift had continued to grow wider between Christian communities and “The Jews.”)

- In the synoptic Gospels Jesus is under the Law (Matthew 5:17-20) and observes the Passover Meal (Matthew 26:17; Mark 14:12; Luke 22:7), whereas Jesus in John is not under the Law and therefore does not partake in the Passover Meal (John 13:1). Accordingly, Johnʼs Jesus refers to “your Law” (John 8:17; 10:34; cf. 7:19; 18:31) and “their Law” (15:25).

- Preaching about the coming kingdom was central to the synoptics and mentioned 17 times in Mark, starting with Mark 1:15 “The time has come,” he said. “The kingdom of God has come near. Repent and believe the good news!” (Matthew changes it to “kingdom of heaven”) Matthew and Luke mention “kingdom of heaven/God” and/or “kingdom” 30 times or more, each). But “kingdom of God” only appears twice in the fourth Gospel and “kingdom” two times. Thatʼs because the fourth Gospel is a later creation and has distanced itself from the apocalyptic Jesus and is busy trying to institutionalize Christianity and Christian sacramental views.

- Jesus of the synoptic gospels is a charismatic healer-exorcist and end-time Suffering Servant who speaks as though a Son of Man will soon arrive to inaugurate the final judgment and bring on the supernatural kingdom of God (Matthew 10:23; Mark 10:18), whereas in the Fourth Gospel Jesus is the Logos incarnate on earth, a God-Man who exorcises no demons but who proclaims a sacramental, mystical, physical, churchly, doctrine of redemption. Itʼs a later version of Jesus. Itʼs a later “sacramental” tale, because baptism and the Lordʼs Supper (“you must eat my flesh and drink my blood or you have NO life within you”) are aligned with the message about the necessity of a “new birth;” itʼs “mystical” because these sacraments produce “union” with God and Christ (“we shall be one”); itʼs “physical” because these sacraments are physical means that produce a physical effect, the glorification of the flesh to make the flesh capable of resurrection; itʼs “churchly” because these sacraments must be administered by the church, for only in the church can the Spirit unite with the elements to produce salvation and/or ensure the resurrection of the flesh.

- In the synoptic Gospels Jesus spoke openly during the day to whomever asked him “how to inherit eternal life,” and placed commands of obedience, such as honoring oneʼs parents, and not stealing from other people, or even giving away oneʼs money to the poor, high on the list of “how to inherit eternal life.” Only in the fourth Gospel does Jesus answer how to inherit eternal life based on the singular necessity of being “born again,” and that singular message was not even taught in public but to a single person “at night,” yet everyone who doubts it is “damned already.” The fourth Gospel more so than the earlier three teaches that one must “believe” or, be “damned.” “Eat the flesh and drink the blood,” or you “have no life within you.” It does not say people will be judged according to their “works” as in Matthew, instead the fourth Gospel states, “The work of God is this: to believe in the one he has sent.”

- The fourth Gospel is filled with “anti-language” according to social scientists. It is not a gospel about “loving oneʼs neighbor/enemies,” neither of which are commanded nor even mentioned in the fourth Gospel, but instead it is about focusing on loving fellow believers and maintaining oneʼs indoctrination, or in the idiom of cults, “love bombing,” and maintaining in-group thinking, while everyone else can go to hell:

The Gospel of John consists of “anti-language” say Social Scientists. It is not a Gospel about “loving oneʼs neighbor/enemies,” but about indoctrination, or in the idiom of cults, “love bombing,” and maintaining in-group thinking

To reiterate points 2) and 3) above, there are plenty of commonsense reasons to doubt that John 3 is something the historical Jesus said. See here.

There are also plenty of commonsense reasons to doubt that the Gospel of Johnʼs tales about the raising of Lazarus (and Jesusʼs anointing by a “sister” of “Lazarus”) is something that happened. See here.

Personal Info About the Author of this Blog

I was born again in my mid-teens, elected president of my Christian campus group. Some of the twists and turns my journey took can be read here.

Today I am what one might call an agnostic though I dislike labels. I have more questions than answers. Philosophy and theology are filled with far more questions than universally compelling answers and evidence. Meanwhile, scientists have yet to agree concerning how the cosmos began, how it will end, or what it “is” in essence, or what its limitations are, or whether other types of cosmoses exist or impinge on ours, or if our cosmos might give rise to others. Not knowing much about the cosmos, yet claiming to know so much about “God” and the region in which He revealed himself in the ancient Near East, a tiny circle where all of His “official” miracles are supposed to have occurred according to the Jewish, Christian and Muslim “holy” writings, strikes me as exclusivistic folly. Rather than exclusivistic religions Iʼd rather have all children on earth taught about the practical moral wisdom (and lessons of the importance of love) from all times and cultures, starting at a very young age and continuing every year, so that the people of earth might discover that they have more in common and might be able to think in terms of global ethics rather than trying to convert everyone to their own “one true faith.” Even then, one can only hope that the right technology arises to ensure the globe will not grow warmer, and that electric grids will not fail as power usage increases worldwide, and that the oceans and lakes and streams can be cleared of their pollutants. That may be too much to hope for. Though I was heartened to hear that some Evangelicals in the U.S. are now defending the theory of evolution (see the BIOLOGOS website), and also explaining to fellow Evangelicals that the ancient Israelites assumed the cosmos was flat, just like their neighbors assumed (see the works of John Walton). While other Evangelicals are even admitting that trying to defend the idea of “biblical inerrancy” isnʼt worth it (see the works of Peter Enns and Kenton L. Sparks).

Additional Pieces

- People who donʼt know me often call me an atheist. But in all honesty… the scientific and NT questions simply run too deep for me to recite with both head and heart any of the creeds of Christianity

- How reliable are the criteria for historical authenticity employed by historical Jesus scholars, and what questions has historical research raised for Christian scholars like James D. G. Dunn, Robert Gundry, and Michael Licona? Not to mention Barbara Brown Taylorʼs questioning of her vocation…

- New Testament Questions Galore From a Wide Range of Christian and Non-Christian Biblical Scholars

- Gospel Trajectories & the Resurrection (questions as well as sources to read or listen to)

- Carnival of Questions for Resurrection Apologists

- Looking Forward To Your Physically Resurrected Body?

- The stories in which Jesus commands the dead to come back to life, grow less secretive, more public, more impressive, and play a more important role in the story when you read them beginning with Mark then Matthew then Luke and ending with the fourth Gospel

- The Word About the Growing Number of Words Allegedly Spoken by the Resurrected Jesus from Mark to Matthew to Luke-Acts and John

Reminds me of a Robert G Ingersoll lecture. Very nice piece Ed.

ReplyDeleteI have answered part of this essay:

ReplyDeletechristianity can answer the important stuff

that's a link

ReplyDelete