According to the Gospels Jesus was anointed with (or received) perfume numerous times in his life. Are all the tales true? Are any of them symbolic, legendary? At his birth Jesus allegedly received a visit from an unknown number of wealthy star gazers (was it two? three? more than three? Matthew does not say) who traveled far to deliver gifts of “frankincense and myrrh” (not to mention an unknown quantity of “gold”), at least thatʼs what the Gospel of Matthew states, none of the other Gospels happen to mention such a tale.

During his adulthood Jesus encountered expensive perfume again when women began anointing him with it. There is one story of the anointing of the adult Jesus in each Gospel. One was sufficient for the purposes of each Gospel author. To try and combine the anointing stories of all four Gospels into a single “life of Jesus” is to ignore the differences between each, and would add up to three separate tales: One found in Mark and Matthew which are in substantial agreement, another in Luke that disagrees with Mark/Matthew, and a third tale in John that features elements of the tales in Mark and Luke but also disagrees with them, giving us a total of three separate anointing stories. So was Jesus anointed three times? Or did the story change over time?

The failure of attempts to harmonize such stories reminds me of similar attempts made by conservative Christians to harmonize stories of “Peterʼs three denials of Jesus” that are found in all four Gospels (a total of twelve denials). The circumstances of each denial disagree as to where, when, and, in response to whom. Some of the individual denials are easier to harmonize with those in other Gospels, some less easy to harmonize. But disagreements between denials were so blatant in some cases that one conservative Christian insisted Peter must have denied Jesus as many times as there are unharmonizable incidents in all four Gospels. That Christian had convinced himself that Peter may have denied Jesus more than three times, maybe six or more times, so long as he could find a way to retain the historical truth of every divinely inspired detail in his Bible and read the Gospels like a single story—instead of four separate stories, including some that changed over time. He continued to argue that his solution of multiplying the total number of denials was the most reasonable, regardless of the fact that each Gospel by itself agrees with the others that Jesus only mentioned three denials by Peter.

Below are the tales of the anointings of Jesus. The tales in Mark and Matthew are probably the earliest and they parallel each other so closely as to suggest a common literary source. They also agree that perfume was poured on Jesusʼ head:

Mark 14:3,8 (NIV) While he was in Bethany, reclining at the table in the home of Simon the Leper, a woman came with an alabaster jar of very expensive perfume, made of pure nard. She broke the jar and poured the perfume on his head…to prepare for my burial.

Matthew 26:6-7,12 (NIV) While Jesus was in Bethany in the home of Simon the Leper, a woman came to him with an alabaster jar of very expensive perfume, which she poured on his head as he was reclining at the table…to prepare me for burial.

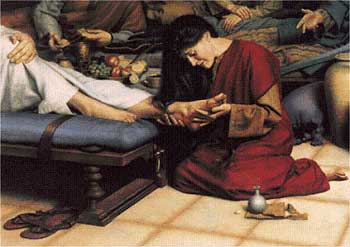

By the time Lukeʼs Gospel was composed the story seems to have changed. It is no longer Jesusʼ head that is anointed with expensive perfume but his feet, by a female sinner who first washes them with her tears and wipes them with her hair, and Luke places the anointing in an early chapter of Jesusʼ ministry, so early that Jesus is shown dining with a Pharisee:

Luke 7:36-38 (NIV) When one of the Pharisees invited Jesus to have dinner with him, he went to the Phariseeʼs house and reclined at the table. A woman in that town who lived a sinful life learned that Jesus was eating at the Phariseeʼs house, so she came there with an alabaster jar of perfume. As she stood behind him at his feet weeping, she began to wet his feet with her tears. Then she wiped them with her hair, kissed them and poured perfume on them.

In all three of the earliest Gospels the woman who anoints Jesusʼ head or feet is not named. But by the time the Gospel of John was composed a name had been allocated to the “anointress” (if I may coin a term), “Mary.” The author even says this was the same “Mary” whom Luke had mentioned in his separate tale of the “two sisters,” one of whom “sat” at Jesusʼ feet listening to him (Luke 10:38-42). But in the Gospel of John this Mary is no longer the one in Luke who merely “sat” at Jesusʼ feet and drew sighs from her sister who wished to scold her for sitting inertly on the floor and leaving her sister with all the kitchen work. Instead, the “Mary” in the Gospel of John is active, dramatically so, for she is depicted as anointing Jesusʼ feet and wiping them with her hair, resembling Lukeʼs anointing story about the unnamed female sinner in the home of the Pharisee. The Gospel of John adds that the whole house was filled with the aroma after about a “pint” of perfume was poured on Jesusʼ feet, so I guess there was no skimping on the perfume per John—nor does John skimp on the perfume in yet another anointing episode found only in that Gospel, but before proceeding to that episode here is the story of Johnʼs “Mary”:

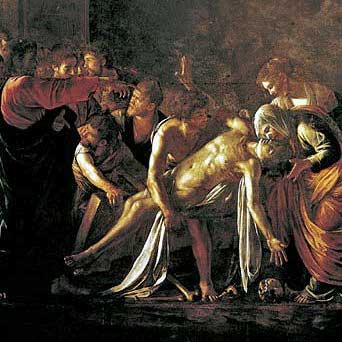

John 12:1-3 (NIV) Six days before the Passover [Note: Jesus dies five days later in this Gospel, on the day before Passover], Jesus came to Bethany, where Lazarus lived, whom Jesus had raised from the dead. Here a dinner was given in Jesusʼ honor. Martha served, while Lazarus was among those reclining at the table with him. Then Mary took about a pint of pure nard [Note: “pure nard” is an unusual and precise phrase that appears in Markʼs earlier version and some commentators suggest that the author of the Gospel of John was acquainted with the tales in both Mark and Luke, combining elements of both to form a third tale], an expensive perfume; she poured it on Jesusʼ feet and wiped his feet with her hair. [Note how this resembles the tale in Luke, but the order in which the perfume is applied and the feet wiped is reversed. In Luke Jesusʼ feet are washed (with tears, something John does not mention) and wiped with hair, and only then is the perfume applied. But in John the perfume is applied and the feet are wiped with hair. So in John, Maryʼs hair is full of perfume, but in Luke the womanʼs hair smelled only of the dirt on Jesusʼ feet. The tale in John differs in this and other respects from earlier anointing tales but also demonstrates some knowledge of the story in Mark and Luke.] And the house was filled with the fragrance of the perfume.

Also, in the Gospel of John not only did the feet of Jesus receive about a pint of perfume, but five days later the same Gospel says Jesusʼ lifeless body was wrapped with “seventy-five pounds of myrrh and aloes.”

But wait, thereʼs another perfume story I have not mentioned, but we must return to the earliest Gospel, Mark, to find it. That Gospel says that after Jesus died some women “saw” where Jesus had been laid and they returned to the tomb a day and a half later carrying “spice” with which they planned to anoint the body. Probably not “seventy-five pounds of myrrh and aloes” as in John, and which was not said to have come from those ladies. But comparing Mark with John and attempting to combine the two stories one might wonder how the ladies who saw where Jesus had been laid also failed to note the odor of seventy-five pounds of myrrh and aloe, an odor that probably followed Jesusʼ body into the tomb or filled the air around it. I would have thought women had better senses of smell, or if they saw Jesusʼ body being hoisted into the tomb they might have at least seen how Jesusʼ body gained 75 pounds of bulky wrappings after he died and that men were straining to maneuver it into the tomb, even on a stretcher, or if the body was not anointed until after it was laid flat in the tomb then perhaps the woman might have seen large jars of spice and wrappings being carried into the tomb. Instead, the early tale in Mark of the hastily buried (and unanointed) body of Jesus, and the tale in John of the heavily anointed body of Jesus simply pass in the night, each going in their own direction without connecting at all.

Of course the differences between the story of Mark and John pose little difficulty once one accepts that the story in Mark is a completely different tale from Johnʼs. Mark imagined Jesus being buried hastily leaving no time for anointing. While John has Jesus laid out in style, seventy five pounds worth of style. The Gospel of Matthew introduces another take on the tale in Mark because in Matthew there is no mention of the women having “spice” and a desire to anoint Jesusʼ body, instead they come to “see” the tomb. Why does Matthew alter the reason why the woman arrive Sunday morning? Because in Matthew the tomb is sealed and guarded (a story found only in Matthew and no where else). So the women would have had no chance of getting near Jesusʼ body let alone “spice” it up, so Matthew says the woman only came to “see” the tomb. Itʼs obvious at this point that different Gospel writers told different stories and changed them to fit with whatever else they wrote.

Returning to the depiction in the Gospel of John, of Jesus having about a pint of perfume poured on his feet by Mary such that the whole house smelled of it, and five days later Jesusʼ body being wrapped with seventy-five pounds of myrrh and aloe, one might wonder if there is any mention in John of the resurrected Jesus smelling of perfume after having arisen a day and a half later and shown himself to a woman and to the apostles. But there is none.

Neither is there mention of the resurrected Jesus smelling of perfume in any of the earlier Gospels. Of course Mark and Matthew, presumably the earliest two Gospels, feature no “seventy-five pound” anointing of “myrrh and aloes” of Jesusʼ body as in John, and they agree that an announcement was made at the empty tomb that Jesus had gone before the apostles to Galilee (“There you will see him”), so, it would take a while to reach Galilee before the apostles would even be near Jesus. Itʼs only in later Gospels (Luke and John) that there is no long delay before the apostles get to see the resurrected Jesus, for neither of those Gospels mention Jesus going ahead to Galilee to be seen there, but instead they have Jesus appearing in Jerusalem on the same day heʼs allegedly resurrected. So Jesus gets to meet the apostles sooner in Luke and John than in the earlier Gospels, Mark and Matthew. But no mention of the resurrected Jesus smelling of perfume in either Luke or John.

Speaking of the resurrection, a story in Luke that has always caught my eye takes place on the day of Jesusʼ resurrection. No time of day is specified, could be late afternoon or evening, doesnʼt say, and the apostles are merely “assembled together” (not cowering behind a “locked door” as in Johnʼs later version), when “Jesus himself stood among them,” and proves he is “not a spirit” but has “flesh and bone,” by eating a piece of fish. The story in Luke continues by claiming that Jesus “led” the apostles out of the city of Jerusalem to the town of Bethany.

I mention this story in Luke because I understand the earlier stories in Mark and Matthew in which Jesus goes ahead of the apostles to Galilee to be seen there, and how it would take the apostles some time to get to Galilee and how some sort of vision could take place out in Galilee, something out of the public eye, away from the big city of Jerusalem. Mark supplies no details at all, just a promise of seeing Jesus in Galilee, while Matthew features a short tale about a sighting in Galilee—but nothing about Jesus trumpeting his physicality, nor boasting about being “flesh and bone” and eating fish—instead, Matthew features a few short words of the risen Jesus, ending with, “but some doubted.” In comparison with the earliest two Gospels (Mark and Matthew) the later Gospels (Luke and John) add more sighting episodes, more elaborate descriptions, more words of the risen Jesus (over a hundred more), and allude to speeches delivered by the risen Jesus, though neither Luke nor John provide them for us to read. After Luke and John there came further stories about Jesus,—the Gospel of John ends by alluding to great numbers of stories then circulating about what Jesus did, “which if all written down I suppose the world could not contain all the books.” Iʼve mentioned this legendary-like development in resurrection stories before, here.

But letʼs take another look at the story in Luke about a resurrected Jesus who was “not a spirit” but “flesh and bone,” and who “led” the apostles out of the city of Jerusalem to the town of Bethany. I assume Jesus was walking and not floating nor spiritually leading the apostles. A walk through Jerusalem, the same town where he was crucified. Was Jesus tempted to walk past the high priestʼs home, past Herodʼs palace, or Pilateʼs? Did the little group walk within sight of the tall Roman garrison building next to the Temple?

A conservative Christian might suggest that the story of such a quiet stroll is no argument against it taking place, and no reason for doubting the inerrant word of God, but the silence in this case is deafening compared with the shouts of Hosannas Jesus had previously received when he rode a donkey into Jerusalem. Compare the two scenes. How somber the triumph of the resurrected Jesus is, everyone in that part of Jerusalem and Bethany oblivious to a dead man walking. Comparing that scene with Jesusʼ public entrance into Jerusalem before his death provides quite a contrast.

I wonder whether any of the apostles in that procession were tempted to converse a bit louder than usual, shout, knock on doors, wave some palms, ask Jesus to show himself to the high priest, preach in public, or announce what a spectacular miracle, as well as a spectacular victory had just occurred. Wasnʼt Jesus more triumphant now than when he had first entered Jerusalem to Hosannas? But no mention in the story is made of joy, of the walkers revealing themselves, nor of anyone recognizing them, nor paying the slightest attention. No one notices the figure in the lead with the holes in his hands and feet (nor looks up after catching a whiff of his perfumed body)? No beggar looks up and sees anything out of the ordinary, perhaps a beggar who would have recognized Jesus having seen him preach in the Temple (with his apostles beside him) a few days earlier? No Roman guards on duty on a corner or at the city gates? No questions asked, no answers offered? As I said, the silence is deafening. But the story seems perfectly suited as a sort of unfalsifiable fantasy told by believers and for believers (equally true of another story in Luke about Jesus walking to Emmaus with two followers, and only revealing who he is for an instant before he “disappears”).

Of course an apologist might suggest that Lukeʼs story about a resurrected Jesus walking the streets of Jerusalem with no fanfare was simply Godʼs way of doing things. But that doesnʼt explain other allegedly God-inspired tales that do involve fanfare:

Jesusʼ death was accompanied by “tombs opening” and “many saints” rising from the dead who “entered the holy city” and “showed themselves to many” on the same day as Jesusʼ own resurrection, a tale told with extreme brevity and only in the Gospel of Matthew (the names of the “saints” were not mentioned, nor the names of any alleged witnesses, not until a century or more after Matthew when some Christians named a few of the alleged “raised saints” and also explained what happened to them—they “vanished” of course, after delivering their testimony to the very same Jewish religious leaders who condemned Jesus at his trial—at least thatʼs what some Christians wrote in The Gospel of Nicodemus, talk about corroborating evidence, Christians have demonstrated that they can invent it as needed)

“Jesus was seen by over five hundred brothers and sisters [believers]” per Paul (By whom? Where? When? Who knows? Neither God nor man preserved such info for us, nor any details about that “appearance,” nor why it took place prior to an appearance to James. Such a tale also seems to have run its course fairly early because it is never mentioned again in any Gospel, nor Acts.)

“Appeared in Galilee” to an unknown number of disciples per Matthew (though “some doubted”)

“Appeared to them [the apostles] over a period of forty days and spoke about the kingdom of God,” and ate food with them during this period, per Acts 1. (I guess they werenʼt public speaking engagements nor public eating engagements during those forty days. Just keepinʼ things private, nothing to see here folks, move along.)

Itʼs not like Jesus wasnʼt “around” per the above boasts, nor other resurrected folks—from the “many raised saints” (mentioned only in Matthew) to a resurrected Lazarus (mentioned only in John) if you believe such tales. Itʼs just that the resurrected Jesus seems shy of the public eye in comparison. Only his spiritual family gets to see him.

Why such shyness? Perhaps Jesus had had enough anointings with expensive perfume: “Enough with the perfume already! From my birth to several times before my death, both head and feet, and then my body before burial, seventy five pounds worth, and then women come to my tomb to try and spice me up some more! In fact Iʼm still sick of the noisy ‘Hosannas’ the time I entered Jerusalem, and the crowd nearly plucked every leaf off those poor palms to wave them in my face and toss them in front of me. And I definitely refuse to show myself to the Pharisees, Herod or Pilate, or any other occupant of Jersualem the majority of whom can remain non-Christian and damned to hell. They have the prophets, and the many raised saints, and Lazarus, why do they need to see the “resurrected me” as well? Next thing you know Iʼll have to appear before Caesar in Rome, and in North America (to found the Mormon church), and in Korea (to found the Unification Church), and soon doubting Thomases everywhere will be begging me to appear to them, but Iʼm not going to offer every Thomas, Dickus and Harryus a chance to stick their hand in my side and believe, including people two thousand years in the future. Damn all those future doubters.

“Instead, Iʼm walking out of town quietly, the same day I show myself to just the apostles, no public celebrations, just a quick nosh on some fish and a stroll out of the city to nearby Bethany and Iʼll ascend from there into heaven. (Luke)

“Maybe not that fast, instead maybe Iʼll hang round with just with my homies for about six weeks, teach them a little more about the kingdom, not that any of them will remember a word I tell them during those six weeks of speaking, nor write it down. (Acts)

“Well, and I might appear to over five hundred believers at once, but just once, and just to brothers and sisters in Christ. (Paul)

“Hmmm, hereʼs a question, where should I be when I appear to the apostles for the first time? In Galilee where I started preaching (Mark & Matthew) or in Jerusalem where I died (Luke & John)? I dunno. Maybe I can inspire them to write that the first time the apostles saw me it was in both places, and we can call that place “Galusalem” or “Jerusalee.” Why be specific? Let people say what they may about the mixed up memories and memoirs of the Gospel writers, and about my lame victory lap out of Jerusalem with no Hosannas (Luke), and no crowds to see me rise up into heaven. Let them say these are ‘just so’ stories or urban myths written by and for believers. It doesnʼt matter. Because if they can believe the story found only in Matthew about the raising of many saints, and the story found only in John of the raising of Lazarus, what wonʼt they believe? At least the believers will believe. As for the doubting Thomasʼs, I repeat, to hell with them. No one will ever get that chance again, not a fully physical post-resurrection meeting just for them. Instead Iʼll leave people some weird tales like that old pulp fiction magazine of the same title, and tell them to believe ʻem or be damned. I am outta here! Looking forward to ascending bodily into heaven and not returning again that way til judgment day (Acts 1).

“Wait a sec, maybe I should think about this a bit more. After all Iʼm not coming back for over 2,000 years, and come to think of it I didnʼt leave behind much in the way of first-person named testimonies to my resurrection. Only that of Paulʼs in fact. And he left behind no description concerning what he saw except to write, ‘he appeared to me,’ thatʼs it. There are stories in Acts about my appearance to Paul and they contain some details but thereʼs also some differences between those stories and none of them were written by Paul, so they arenʼt first-person testimonies, and the author of Acts isnʼt even named.

“Also, I hope people donʼt get confused as to what ‘appearance’ means based on what Paul is going to write in 1 Corinthians 15, because later writings (Luke & Acts) will tell people that my resurrected ‘flesh and bone’ body had already ascended into heaven before I ‘appeared’ to Paul, and that body wasnʼt going to be seen again until the day of final judgment (Acts 1), therefore whatever ‘appeared’ to Paul it wasnʼt my resurrected body, since that had already ascended into heaven. But darn it, Paul equated my ‘appearance’ to him as if it was the same as my ‘appearances’ to others, so the earliest mention of my ‘appearances’ makes no distinctions as to what ‘appeared’:

1 Corinthians 15 (NIV) He appeared to Cephas, and then to the Twelve. After that, he appeared to more than five hundred of the brothers and sisters at the same time, most of whom are still living, though some have fallen asleep. Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles, and last of all he appeared to me also, as to one abnormally born.

“Yup, that letter of Paulʼs is going to make things sounds a bit vague and sketchy, that I ‘appeared’ to the apostles and to Paul, without distinguishing between them. All just ‘appearances.’ All equal. Oh well.

“And what about that line sandwiched in between the appearances to Cephas and James, the line that I ‘appeared to more than five hundred of the brothers and sisters at the same time.’ Decades after that statement, the book of Acts is going to imply that there were far less than ‘five hundred’ brethren around after my body had already ascended into heaven. Acts 1:15 says that Peter preached to only ‘one hundred and twenty’ brethren, much less than ‘over five hundred,’ and my resurrected body had already ascended into heaven. That means people will question whether I was still on earth in my resurrection body when I appeared to ‘over five hundred brothers and sisters.’ Neither could Paul have seen my resurrection body if Acts 1 is correct, yet he speaks of my appearance to him as though it was equal to that of my appearances to the apostles.

“It also irks me that there will never be any mention made of to whom, when, or where I appeared in 1 Cor. 15. But I guess thatʼs alright since the stories in 1 Cor. 15 of my appearance to Cephas alone, and James alone, and ‘over five hundred brethren,’ are going to die out pretty quickly and never be repeated in the Gospels or Acts.

“In fact in the Gospel that will be composed last of all and lay furthest from 1 Cor. 15 some of those stories about me appearing to a lone person and then to the apostles will be reversed, and the even the name changed of the lone person. In the last written Gospel (John) it will say that I appeared to all the apostles except one, Thomas, and then that I came back a little later to show myself specifically to that lone apostle after he had gathered together with them. Paul in 1 Cor. 15 features no knowledge of that later tale about me coming back to be seen by Thomas, and it will seem strange to readers how that tale in John is like the opposite of the ones in 1 Cor. 15, and even changes the name of the apostle.

“Sheesh, speaking of things Paul wonʼt mention but later writings like the Gospels will mention, thereʼs the story of my very first appearance, not to Cephas and the apostles, nor to over five hundred brethren, nor to James and the apostles, but to women. The story of my first appearance “to women” wonʼt even appear in the earliest Gospel, Mark, where all that the women see is a young man in white who tells them Jesus has gone ahead to Galilee. So the story about my first appearance to women will only start to be told in the next Gospel, Matthew. Paul wonʼt even mention the story of the “empty tomb” found in the earliest Gospel (Mark). So it will definitely look like the stories of my appearances to women and leaving a tomb empty arose later.

“Nor will Paul mention anything about me being born of a virgin, which is yet another story that didnʼt begin with the earliest Gospel (Mark), but with two later Gospels, Matthew and Luke. So some people might suspect these Gospel stories were legendary elaborations that arose over time.

“Yup, Paulʼs list of mere ‘appearances’ in 1 Cor. 15 is going to make it look like all that Paul had to work with were early mania-driven ill-defined ‘appearance’ stories, and that the Gospel tales including the empty tomb and appearances to women arose later. Even the author of the earliest Gospel will make it look like the empty tomb story arose later, because that Gospel will end with these words:

Mark 16:8 (NIV) Trembling and bewildered, the women went out and fled from the tomb. They said nothing to anyone, because they were afraid.

So the earliest story about the empty tomb implies the women were not running with joy to tell the apostles of what they had seen as in The Gospel of Matthewʼs later version of the story, but instead the earliest version of the empty tomb story will end with “They said nothing to anyone,” which will make readers think the story of the empty tomb itself could have arisen later, as a legend people began telling each other because the women themselves had originally been silent about what they had seen.

“Luckily I also know that people arenʼt going to think about these stories, their chronological order, and make such observations, not like I just did, at least not until eighteen centuries or so have passed after my death. Even then, most Christians wonʼt bother. They will continue reading the Gospels, jumbling stories together in their minds, like they teach their children to do at Christmas pageants that jumble together the stories of my birth and how and why I wound up born in Bethlehem yet raised in Nazareth. Or like they do—but on a far higher level of rationalization—whenever they attempt to write books about ‘systematic theology.’ They even jumble up Greek metaphysical ideals about an infinite God with the anthropomorphic images of God in the Bible, and imagine they have proved something, or thwarted all questions. Which is great, I mean who really has time to be deal with questions? Pick your systematic theologian and go for it, donʼt look back, donʼt be a doubting Thomas.

“In fact Iʼm gonna make things simple and just damn people for being doubting Thomases, for daring to question things in the past they can no longer see nor hear for themselves, for daring to question stories in a book. Iʼm going to damn those who publicly admit they have questions and that studies of history remain uncertain. And for doubting Creedal formulas concerning who I was and am and will be. And for not making perfect sense out of how shedding my blood fixes the past, present and future, and makes forgiveness possible, or for doubting the Trinity. Damn them for daring to doubt things no one can prove, things that do not make perfect rational sense but continue to be debated even by those that love me. And for daring to bring up the Messiah-mania and superstitious nature of beliefs during the first century.

“People donʼt need evidence, they donʼt need first-person named testimonies. The only one Iʼll give them is from Paul who wrote, ‘He appeared to me.’ (A lot of the other NT letters by ‘apostles’ are disputed or apocryphal and say no more than that, and most say even less than that.) Paul is the one who put Christianity on the map, along with his Gentile converts.

“Neither do people need testimonies from people who personally saw a few startling things but were not brethren themselves. Iʼll leave them stories written by brethren and for brethren, and I wonʼt stop brethren from continuing to add more stories and edit previous ones together so that weʼll have four Gospels with literary links between them, and five, six or more Gospels composed later, let them keep writing things like The Gospel of Peter, The Gospel of Nicodemus, The Apocalypses of Peter and Paul, Nativity Gospels, and a host of other Christian compositions, exactly as the Jews continued to write inter-testamental literature. They didnʼt stop after the OT was “complete.” Even the collection of holy books found among the Dead Sea Scrolls illustrate that that group of Jews had a broader canon than the one the Jews recognize today.

“Iʼll also leave my followers a few historical crumbs, a few disputed lines about me in the works of Josephus, a man who will never have met me but who will stitch together a few lines about me based on things he will hear second, third hand, etc. Neither am I going to go out of my way to try and preserve long scrolls or codices/books from the first century when I walked the earth, let all first century Christian writing rot. At most Iʼll only leaven my followers a few second century fragments, and a few quotations of Gospel passages or stories in some church fathers, but no whole Gospels till the fourth century. But I also think Iʼll mess with people and find a way to preserve a whole batch of scrolls near the Dead Sea that demonstrate the existence of Jewish apocalyptic-mania both before and right after my day.

“After all, people donʼt need evidence, just stories that move them. Novels and comic books, thatʼs what sells, characters, fiction, drama, and miracles as well. Who cares that the earliest writings that I will choose to inspire and preserve for future generations (those by Paul and the Gospel of Mark) will both lack descriptions of my post resurrection ‘appearances.’ Theyʼll just say ‘he appeared.’ Paul wonʼt even say where. Then Mark will add ‘Galilee,’ and Matthew will agree with Mark but add a quickie appearance of me to some women near the tomb, and then the appearance in Galilee to the apostles. Later, Luke and John will claim I appeared to the disciples in Jerusalem, on the same day as my resurrection.

“Also, who cares that the earliest Gospel Mark, will lack stories about my birth and even lack descriptions concerning my post-resurrection appearances? Mark will begin only with my baptism and end with an empty tomb a promise of seeing me in Galilee. Thatʼs it. The Gospels that come after Mark will differ most from each other in exactly those places where Mark didnʼt have any tales to tell, which makes it look like Matthew and Luke filled in Markʼs blanks with legends and divergent tales that Christians themselves began to tell each other after more converts arose and more of them grew curious about Markʼs blanks. Matthew and Luke tried filling in those blanks, and wound up differing most from each other in exactly those areas where Mark was blank, i.e., in their new tales and descriptions of my post-resurrection appearances (and in tales related to how and why I was born in Bethlehem yet raised in Nazareth).

“Gotta run. Canʼt say when Iʼll be back. Of course things will be hellish on earth in the future, plagues, famines, maybe even an asteroid or solar flare damaging the earth and dragging down civilization, which is why I hope youʼll keep the Bible in print, because if you only try to preserve it in e-book format in the future, good luck. Oh, sure, the Bible wonʼt tell you how to survive the coming difficulties. Itʼs just a book about fearing him who can kill both body and soul and cast you into hell. Oh yeah, and loving your neighbor. So read and tremble! And marvel at the strange mixed up tales of my resurrection! Everybodyʼs gotta believe something.”