Major historical Jesus scholar, James D. G. Dunn (who is very moderate but not liberal) doubts that Jesus spoke a word attributed to him in Johnʼs Gospel. Even conservative Christian scholars of New Testament and Greek like David A. Croteau of Columbia International University (Columbia, South Carolina) claim that the words attributed to Jesus in the fourth Gospel are unlikely to be the literal words Jesus used, but more like the author relaying the spirit of Jesusʼs teachings. Reasons for doubt in the case of John 3:16 seem obvious enough…

Letʼt start with what Dr. Croteau says in Urban Legends of the New Testament: 40 Common Misconceptions (pub. 2015), and then add Ehrmanʼs and Straussʼs comments.

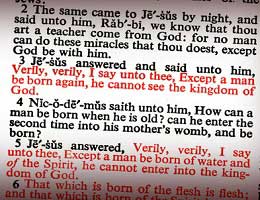

According to Croteau, it is a Christian “urban myth” that “Jesus spoke the most famous Bible verse in John 3:16. This myth holds that the red letters in modern Bibles indicate that Jesus spoke John 3:16. But it is unlikely Jesus spoke these words that editors of different Bibles chose to highlight with red letters, because the language is more typical of the author of the Gospel of John, and 3:16 would be redundant for Jesus to speak just after he spoke 3:15. Also, 3:16 speaks of Jesus dying in the past which makes it more likely for the author of that Gospel to have spoken it rather than Jesus himself.” But in the end, itʼs still a thumbs up verse for Croteau, “it doesnʼt matter who spoke the words, they are equally inspired.”

The above is an Evangelicalʼs admission. But letʼs delve deeper, because when you read Ehrman and Strauss you soon find commonsense reasons to question whether the entire conversation in John chapter 3 between Jesus and Nicodemus ever took place.

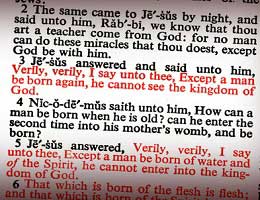

Here is the conversation:

John 3 New American Standard Bible (NASB)

Now there was a man of the Pharisees, named Nicodemus, a ruler of the Jews;

this man came to Jesus by night and said to Him, “Rabbi, we know that You have come from God as a teacher; for no one can do these signs that You do unless God is with him.”

Jesus answered and said to him, “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless one is born again [Greek, “anathon”] he cannot see the kingdom of God.”

Nicodemus said to Him, “How can a man be born when he is old? He cannot enter a second time into his motherʼs womb and be born, can he?”

Jesus answered, “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless one is born of water and the Spirit he cannot enter into the kingdom of God.

That which is born of the flesh is flesh, and that which is born of the Spirit is spirit.

Do not be amazed that I said to you, “You must be born again [Greek, ‘anathon’].”

The wind blows where it wishes and you hear the sound of it, but do not know where it comes from and where it is going; so is everyone who is born of the Spirit.”

Nicodemus said to Him, “How can these things be?”

Jesus answered and said to him, “Are you the teacher of Israel and do not understand these things?

Truly, truly, I say to you, we speak of what we know and testify of what we have seen, and you do not accept our testimony.

If I told you earthly things and you do not believe, how will you believe if I tell you heavenly things?

No one has ascended into heaven, but He who descended from heaven: the Son of Man.

As Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of Man be lifted up;

so that whoever believes will in Him have eternal life.

For God so loved the world, that He gave His only begotten Son, that whoever believes in Him shall not perish, but have eternal life.

For God did not send the Son into the world to judge the world, but that the world might be saved through Him.

He who believes in Him is not judged; he who does not believe has been judged already, because he has not believed in the name of the only begotten Son of God.

This is the judgment, that the Light has come into the world, and men loved the darkness rather than the Light, for their deeds were evil.

For everyone who does evil hates the Light, and does not come to the Light for fear that his deeds will be exposed.

But he who practices the truth comes to the Light, so that his deeds may be manifested as having been wrought in God.”

After reading the above note that the Gospel of John was composed in Greek, yet Jews in Jesusʼ day spoke Aramaic, so two Jews holding a conversation, such as Nicodemus and Jesus in the Jewish city of Jerusalem, would most likely have been speaking Aramaic rather than Greek to one another. And that means Nicodemus would not have been confused as to the double-meaning of the Greek word “anathon,” which could mean either “again” or “from above,” and which Nicodemus heard as “Ye must be born AGAIN” but which Jesus used in the sense of “Ye must be born FROM ABOVE.” Neither is there any word in Aramaic with such a double meaning according to Bart Ehrman, who told me that the Aramaic word for “again” does not also mean “from above,” nor does the Aramaic word for “from above” mean “again.” So why was Nicodemus confused? Probably because the conversation was invented by a Greek speaking storyteller or perhaps by the author of the Gospel of John himself.

In an email recʼd 9/4/11, Ehrman added:

The conversation makes much better sense as hinging on a mistaken double entendre, as happens, in fact, in the very next chapter where the woman thinks that Jesusʼ reference to “living water” means “running water” (since that is how it is normally described in Greek), when in fact he means “water that gives life.” Both conversations proceed by a double entendre, misunderstood, leading to a re-explanation. That works only if there is in fact a double entendre, possible in Greek but not Aramaic.

Furthermore, the author of the Gospel of John utilizes certain dualistic ideas and characteristic phrases which first appear in the authorʼs lengthy prologue as well as in the mouth of John the Baptist, as well as in the mouth of Jesus such dualisms include:

“earthly and heavenly things”

“flesh and spirit”

“darkness and light”

“truth and lies”

“eternal life and death”

and the conversation in John 3 is no exception. It appears like the author of the fourth Gospel invented this conversation as one more of his dualistic sermons about things earthly and heavenly, and so he employed the Greek word, anothen, with its dual meaning, as well as the Greek word pneuma with its dual meaning since pneuma could refer to either “wind” or “spirit,” and a third dualistic phrase as well, all in the same “dialogue with Nicodemus.”

Now read John, chapter 3, below with the above in mind:

Jesus replied, “Very truly I tell you, no one can see the kingdom of God unless they are born again/from above.” “How can someone be born when they are old?” Nicodemus asked [picking up on the “again” meaning of anothen, but ignoring the “from above” meaning]. “Surely they cannot enter a second time into their motherʼs womb to be born!” Jesus answered, “Very truly I tell you, no one can enter the kingdom of God unless they are born of water and the Spirit. Flesh gives birth to flesh, but the Spirit gives birth to spirit. You should not be surprised at my saying, ‘You must be born again/from above.’

Jesus continues by applying another double meaning:

The wind [=pneuma, the same Greek word for spirit] blows wherever it pleases. You hear its sound, but you cannot tell where it comes from or where it is going. So it is with everyone born of the Spirit [=pneuma, spirit/wind in Greek]. “How can this be?” Nicodemus asked.

Nicodemus is confused a second time by the authorʼs use of a Greek word with a dual meaning that applies both to earthly and heavenly things, “wind,” and “spirit,” but unlike the previous case the word pneuma had the same dual meaning in Greek as well as Aramaic and Hebrew, meaning both “wind” and “spirit” in all three languages, since the wind appeared invisible and mysterious/spiritual to all ancient cultures (viz., the “spirit/wind, or even breath” [of life]).

Jesus continues by applying a third double meaning:

“You are Israelʼs teacher,” said Jesus, “and do you not understand these things? Very truly I tell you, we speak of what we know, and we testify to what we have seen, but still you people do not accept our testimony. I have spoken to you of earthly things and you do not believe; how then will you believe if I speak of heavenly things? [my emphasis] No one has ever gone into heaven except the one who came from heaven—the Son of Man. Just as Moses lifted up [the same Greek word for lifted up also means exalted] the snake in the wilderness, so the Son of Man must be lifted up [the same Greek word for “lifted up” also means “exalted,” a third play on words], that everyone who believes may have eternal life in him.” [end of John 3:3-15]

The author continues in that same chapter in dualistic fashion by teaching that you either,

“believe in the name of Godʼs one and only Son,” or,

you are “condemned already,”

and

you either “love the light” or,

you “love the darkness.”

This is not the Jesus of the synoptics who taught that oneʼs deeds mattered more than what one believed about Jesus, and who said people could be forgiven even if they blasphemed the son of man.

John 3:16-21, the tagline one might say to the conversation with Nicodemus, but note that in the NIV there are no quotation marks around this paragraph, so not even the editors of the NIV assume that Jesus spoke these words, rather these words appear to be the authorʼs—his tagline to the story of Jesusʼ conversation with Nicodemus, just like the lengthy prologue to his Gospel which also were the authorʼs words, not Jesusʼ:

For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life. For God did not send his Son into the world to condemn the world, but to save the world through him. Whoever believes in him is not condemned, but whoever does not believe stands condemned already because they have not believed in the name of Godʼs one and only Son. This is the verdict: Light has come into the world, but people loved darkness instead of light because their deeds were evil. Everyone who does evil hates the light, and will not come into the light for fear that their deeds will be exposed. But whoever lives by the truth comes into the light, so that it may be seen plainly that what they have done has been done in the sight of God.

Further Questions Related to the Fictional Nature of the Dialogue Between Jesus & Nicodemus in the Fourth Gospel

The biblical scholar David Friedrich Strauss examined the dialogue between Nicodemus and Jesus and like Ehrman found the historicity of such a dialogue questionable for a variety of reasons.

Conversation of Jesus with Nicodemus by David Friedrich Strauss

The first considerable specimen which the fourth gospel gives of the teaching of Jesus, is his conversation with Nicodemus (3.1-21). In the previous chapter (23-25) it is narrated, that during the first Passover attended by Jesus after his entrance on his public ministry, he had won many to faith in him by the miracles which he performed, but that he did not commit himself to them because he saw through them: he was aware, that is, of the uncertainty and impurity of their faith. Then follows in our present chapter, as an example, not only of the adherents whom Jesus had found even thus early, but also of the wariness with which he tested and received them, a more detailed account how Nicodemus, a ruler of the Jews and a Pharisee, applied to him, and how he was treated by Jesus.

It is through the Gospel of John alone that we learn anything of this Nicodemus, who in 7.50f. appears as the advocate of Jesus, so far as to protest against his being condemned without a hearing, and in 19.39 as the partaker with Joseph of Arimathea of the care of interring Jesus. Modern criticism, with reason, considers it surprising that in all three synoptic Gospels, Mark, Matthew and Luke, there is no mention of the name of this remarkable adherent of Jesus, and that we have to gather all our knowledge of him from the fourth gospel (John); since the peculiar relation in which Nicodemus stood to Jesus, and his participation in the care of his interment, must have been as well known to Matthew a.s to John. This difficulty has been numbered among the arguments which are thought to prove that the first gospel was not written by the Apostle Matthew, but was the product of a tradition considerably more remote from the time and locality of Jesus. But the fact is that the common fund of tradition on which all three synoptic Gospels (Mark, Matthew, Luke) drew had preserved no notice of this Nicodemus. With touching piety the Christian legend has recorded in the tablets of her memory, the names of all the others who helped to render the last honors to their murdered master of Joseph of Arimathea and the two Marys (Matt 27.57-61 with parallels in other Gospels); why then was Nicodemus the only neglected one he who was especially distinguished among those who tended the remains of Jesus, by his nocturnal interview with the teacher sent from God, and by his advocacy of him among the chief priests and Pharisees? It is so difficult to conceive that the name of this man, if he had really assumed such a position, would have vanished from the popular evangelical tradition without leaving a single trace, that one is induced to inquire whether the contrary supposition be not more capable of explanation: namely, that such a relation between Nicodemus and Jesus might have been fabricated by tradition, and adopted by the author of the fourth gospel without having really subsisted.

John 12.42, it is expressly said that many among the chief rulers believed on Jesus, but concealed their faith from dread of excommunication by the Pharisees, because they loved the praise of men more than the praise of God. That towards the end of his career many people of rank believed in Jesus, even in secret only, is not very probable, since no indication of it appears in the Acts of the Apostles ; for that the advice of Gamaliel (Acts 5.34 ff.) did not originate in a positively favorable disposition towards the cause of Jesus, seems to be sufficiently demonstrated by the spirit of his disciple Saul. Moreover the synoptists make Jesus declare in plain terms that the secret of his Messiahship had been revealed only to babes, and hidden from the wise and prudent (Matt. 11.25; Luke 10.21), and Joseph of Arimathea is the only individual of the ruling class whom they mention as an adherent of Jesus.

How, then, if Jesus did not really attach to himself any from the upper ranks, came the case to be represented differently at a later period? In John 7.48f we read that the Pharisees sought to disparage Jesus by the remark that none of the rulers or of the Pharisees, but only the ignorant populace, believed on him; and even later adversaries of Christianity, for example, Celsus, laid great stress on the circumstance that Jesus had had as his disciples. This reproach was a thorn in the side of the early church, and though as long as her members were drawn only from the people, she might reflect with satisfaction on the declarations of Jesus, in which he had pronounced the poor, and simple, blessed : yet so soon as she was joined by men of rank and education, these would lean to the idea that converts like themselves had not been wanting to Jesus during his life. But, it would be objected, nothing had been hitherto known of such converts. Naturally enough, it might be answered ; since fear of their equals would induce them to conceal their relations with Jesus. Thus a door was opened for the admission of any number of secret adherents among the higher class (John 12.42f). But, it would be further urged, how could they have intercourse with Jesus unobserved ? Under the veil of the night, would be the answer ; and thus the scene was laid for the interviews of such men with Jesus (19.39). This, however, would not suffice ; a representative of this class must actually appear on the scene : Joseph of Arimathea might have been chosen, his name being still extant in the synoptical tradition ; but the idea of him was too definite, and it was the interest of the legend to name more than one eminent friend of Jesus. Hence a new personage was devised, whose Greek name (Nicodemus) seems to point him out significantly as the representative of the dominant class. That this development of the legend is confined to the fourth gospel, is to be explained, partly by the generally admitted lateness of its origin, and partly on the ground that in the evidently more cultivated circle in which it arose, the limitation of the adherents of Jesus to the Common people would be more offensive, than in the circle in which the synoptical tradition was formed. Thus the reproach which modern criticism has cast on the first gospel, on the score of its silence respecting Nicodemus, is turned upon the fourth, on the score of its information on the same subject.

These considerations, however, should not create any prejudice against the ensuing conversation, which is the proper object of our investigations. This may still be in the main genuine; Jesus may have held such a conversation with one of [his adherents, and our Evangelist may have embellished it no further than by making this interlocutor a man of rank. Neither will we, with the author of the Probabilia, take umbrage at the opening address of Nicodemus, nor complain, with him, that there is a want of connexion between that address and the answer of Jesus. The requisition of a new birth, as a condition of entrance into the kingdom of heaven, does not differ essentially from the summons with which Jesus opens his ministry in the synoptical gospels, Repent ye, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand. New birth, or new creation, was a current image among the Jews, especially as denoting the conversion of an idolater into a worshiper of Jehovah. It was customary to say of Abraham, that when, according to the Jewish supposition, he renounced idolatry for the worship of the true God, he became a new creature. The proselyte, too, in allusion to his relinquishing all his previous associations, was compared to a new-born child. That such phraseology was common among the Jews at that period, is shown by the confidence with which Paul applies, as if it required no explanation, the term new creation, to those truly converted to Christ. Now, if Jesus required, even from the Jews, as a condition of entrance into the messianic kingdom, the new birth which they ascribed to their heathen proselytes, Nicodemus might naturally wonder at the requisition, since the Israelite thought himself, as such, unconditionally entitled to that kingdom : and this is the construction which has been put upon his question 5.4. But Nicodemus does not ask, How canst thou say that a Jew, or a child of Abraham, must be born again? His ground of wonder is that Jesus appears to suppose it possible for a man to be born again, and that when he is old. It does not, therefore, astonish him that spiritual new birth should be expected in a Jew, but corporeal new birth in a man. How an oriental, to whom figurative speech in general how a Jew, to whom the image of the new birth in particular must have been familiar how especially a master of Israel, in whom the misconstruction of figurative phrases cannot, as in the apostles (e.g. Matt. 15.15f; 16.7), be ascribed to want of education could understand this expression literally, has been matter of extreme surprise to expositors of all parties, as well as to Jesus (5.10). Hence some have supposed that the Pharisee really understood Jesus, and only intended by his question to test the ability of Jesus to interpret his figurative expression into a simple proposition: but Jesus does not treat him as a hypocrite, as in that case he must have done he continues to instruct him, as one really ignorant(5.10). Others give the question the following turn : This cannot be meant in a physical sense, how then otherwise? But the true drift of the question is rather the contrary : By these words I can only understand physical new birth, but how is this possible? Our wonder at the ignorance of the Jewish doctor, therefore, returns upon us; and it is heightened when, after the copious explanation of Jesus (5.5-8), that the new birth which he required was a spiritual birth, Nicodemus has made no advance in comprehension, but asks with the same obtuseness as before (5.9), How can these things be? By this last difficulty one apologist who tries to argue for the historicity of the tale is so destitute of excuses, that, contrary to his ordinary exegetical tact, he refers the continued amazement of Nicodemus—as other expositors had referred his original question—to the circumstance that Jesus maintained the necessity of new birth even for Israelites. But, in that case, Nicodemus would have inquired concerning the necessity, not the possibility, of that birth; instead of asking, How can these things be? he would have asked, Why must these things be? This inconceivable mistake in a Jewish doctor is not then to be explained away, and our surprise must become strong suspicion so soon as it can be shown, that legend or the Evangelist had inducements to represent this individual as more simple than he really was. First, then, it must occur to us, that in all descriptions and recitals, contrasts are eagerly exhibited; hence in the representation of a colloquy in which one party is the teacher, the other the taught, there is a strong temptation to create a contrast to the wisdom of the former by exaggerating the simplicity of the latter. Further, we must remember the satisfaction it must give to a Christian mind of that age, to place a master of Israel in the position of an unintelligent person, by the side of the Master of the Christians. Lastly, it is, as we shall presently see more clearly, the constant method of the fourth Evangelist in detailing the conversations of Jesus, to form the knot and the progress of the discussion, by making the interlocutors understand literally what Jesus intended figuratively.

In reply to the second query of Nicodemus, Jesus takes entirely the tone of the fourth Evangelistʼs prologue (5.11-13). The question hence arises, whether the Evangelist borrowed from Jesus, or lent to him his own style. A previous investigation has decided in favor of the latter alternative. But this inquiry referred merely to the form of the discourses; in relation to their matter, its analogy with the ideas of Philo, does not authorize us at once to conclude that the writer here puts his Alexandrian doctrine of the Logos into the mouth of Jesus; because the expressions, “We speak that we do know,” etc., and, “No man hath ascended up to heaven,” etc., have an analogy with Matt. 11.27; and the idea of the pre-existence of the Messiah which is here propounded, is, as we have seen, not foreign to the Apostle Paul.

In chapter 5.14 & 15 Jesus proceeds from the more simple things of the earth, the communications concerning the new birth, to the more difficult things of heaven, the announcement of the destination of the Messiah to a vicarious death. The Son of Man, he says, must be lifted up (which, in Johnʼs phraseology, signifies crucifixion, with an allusion to a glorifying exaltation), in the same way, and with the same effect, as the brazen serpent in Num. 21.8,9. Here many questions press upon us. Is it credible, that Jesus already, at the very commencement of his public ministry, foresaw his death, and in the specific form of crucifixion? and that long before he instructed his disciples on this point, he made a communication on the subject to a Pharisee? Can it be held consistent with the wisdom of Jesus as a teacher, that he should impart such knowledge to Nicodemus? Even a conservative theologian like Lucke puts the question why, when Nicodemus had not understood the more obvious doctrine, Jesus tormented him with the more recondite, and especially with the secret of the Messiahʼs death, which was then so remote? Luckeʼs ingenious proposal to try and explain such away such a question is to propose that ‘it accords perfectly with the wisdom of Jesus as a teacher, that he should reveal the sufferings appointed for him by God as early as possible, because no instruction was better adapted to cast down false worldly hopes;’ or to say it another way, the more remote the idea of the Messiahʼs death from the conceptions of his contemporaries, owing to the worldliness of their expectations, the more impressively and unequivocally must Jesus express that idea, if he wished to promulgate it; not in an enigmatical form which he could not be sure that Nicodemus would understand. Lucke continues: “Nicodemus was a man open to instruction; one of whom good might be expected. But in this very conversation, his dullness of comprehension in earthly things, had evinced that he must have still less capacity for heavenly things; and, according to 5.12, Jesus himself despaired of enlightening him with respect to them. Lucke, however, observes, that it was a practice with Jesus to follow up easy doctrine which had not been comprehended, by difficult doctrine which was of course less comprehensible; that he purposed thus to give a spur to the minds of his hearers, and by straining their attention, engage them to reflect. But the examples that Lucke adduces of such proceeding on the part of Jesus, are all drawn from the fourth gospel. Now the very point in question is, whether that gospel correctly represents the teaching of Jesus; consequently Lucke argues in a circle. We have seen a similar procedure ascribed to Jesus in his conversation with the woman of Samaria, and we have already declared our opinion that such an overburdening of weak faculties with enigma on enigma, does not accord with the wise rule as to the communication of doctrine, which the same gospel puts into the mouth of Jesus, 16.12. It would not stimulate, but confuse, the mind of the hearer, who persisted in a misapprehension of the well-known figure of the new birth, to present to him the novel comparison of the Messiah and his death, to the brazen serpent and its effects; a comparison quite incongruous with his Jewish ideas. In the first three Gospels Jesus pursues an entirely different course. In these, where a misconstruction betrays itself on the part of the disciples, Jesus (except where he breaks off altogether, or where it is evident that the Evangelist unhistorically associates a number of metaphorical discourses) applies himself with the assiduity of an earnest teacher to the thorough explanation of the difficulty, and not until he has effected this does he proceed, step by step, to convey further instruction (e.g. Matt. 13.10 ff, 36 ff, 15.16, 16.8 ff.). This is the method of a wise teacher; on the contrary, to leap from one subject to another, to overburden and strain the mind of the hearer, a mode of instruction which the fourth Evangelist attributes to Jesus, is wholly inconsistent with that character. To explain this inconsistency, we must suppose that the writer of the fourth gospel thought to heighten in the most effective manner the contrast which appears from the first, between the wisdom of the one party and the incapacity of the other, by representing the teacher as overwhelming the pupil, who put unintelligent questions on the most elementary doctrine, with lofty and difficult themes, beneath which his faculties are laid prostrate.

From 5.16, even those commentators who pretend to some ability in this department, lose all hope of showing that the remainder of the discourse may have been spoken by Jesus. Not only does Paulus make this confession, but even Olshausen, with a concise statement of his reasons. At the above verse, any special reference to Nicodemus vanishes, and there is commenced an entirely general discourse on the destination of the Son of God, to confer a blessing on the world, and on the manner in which unbelief forfeits this blessing. Moreover, these ideas are expressed in a form, which at one moment appears to be a reminiscence of the Evangelistʼs introduction, and at another has a striking similarity with passages in the first Epistle of John. In particular, the expression, the only begotten Son, which is repeatedly (5.16 & 18) attributed to Jesus as a designation of his own person, is nowhere else found in his mouth, even in the fourth gospel; this circumstance, however, marks it still more positively as a favorite phrase of the Evangelist (1.14-18), and of the writer of the Epistles (1 John 4.9).

Further, many things are spoken of as past, which at the supposed period of this conversation with Nicodemus were yet future. For even if the words, he gave, refer not to the giving over to death, but to the sending of the Messiah into the world; the expressions, “men loved darkness,” and, “their deeds were evil,” (5.19), as Lucke also remarks, could only be used after the triumph of darkness had been achieved in the rejection and execution of Jesus: they belong then to the Evangelistʼs point of view at the time when he wrote, not to that of Jesus when on the threshold of his public ministry.

In general the whole of this discourse attributed to Jesus, with its constant use of the third person to designate the supposed speaker; with its dogmatical terms, “only begotten,” “light,” and the like, applied to Jesus; with its comprehensive view of the crisis and its results, which the appearance of Jesus produced, is far too objective for us to believe that it came from the lips of Jesus. Jesus could not speak thus of himself, but the evangelist might speak thus of Jesus. Hence the same expedient has been adopted by some conservative theologians, as in the case of the Baptistʼs discourse already considered, and it has been supposed that Jesus is the speaker down to 5.16, but that from that point the Evangelist appends his own dogmatic reflections. But there is again here no intimation of such a transition in the text; rather, the connecting word “for,” yap (5.16), seems to indicate a continuation of the same discourse. No writer, and least of all the fourth Evangelist (comp. 7.39, 11.51 f., 12.16, 33.37 ff.), would scatter his own observations thus undistinguishingly, unless he wished to create a misapprehension.

If then it be established that the evangelist, from 5.16 to the end of the discourse, means to represent Jesus as the speaker, while Jesus can never have so spoken, we cannot rest satisfied with the half measure adopted by Lucke, when he maintains that it is really Jesus who continues to speak from the above passage, but that the Evangelist has woven in his own explanations and amplifications more liberally than before. For this admission undermines all certainty as to how far the discourse belongs to Jesus, and how far to the Evangelist ; besides, as the discourse is distinguished by the closest uniformity of thought and style, it must be ascribed either wholly to Jesus or wholly to the Evangelist. Of these two alternatives the former is, according to the above considerations, impossible ; we are therefore restricted to the latter, which we have observed to be entirely consistent with the manner of the fourth Evangelist.

But not only on the passage 5.16-21 must we pass this judgment: 5.14 has appeared to us out of keeping with the position of Jesus ; and the behaviour of Nicodemus, 5.4 & 9, altogether inconceivable. Thus in the very first sample, when compared with the observations which we have already made on John 3.22 ff., 4.1 ff, the fourth gospel presents to us all the peculiarities which characterize its mode of reporting the discourses of Jesus. They are usually commenced in the form of dialogue, and so far as this extends, the lever that propels the conversation is the striking contrast between the spiritual sense and the carnal interpretation of the language of Jesus ; generally, however, the dialogue is merged into an uninterrupted discourse, in which the writer blends the person of Jesus with his own, and makes the former use concerning himself, language which could only be used by John concerning Jesus.

Recently Straussʼ work has been made available in audio format free online,

- HERE,

- HERE.

For Straussʼ questions regarding the historicity of Nicodemus in particular see, The Life of Jesus Critically Examined, Part 2 - History of the Public Life of Jesus Chapter 7 - Discourses of Jesus in the Fourth Gospel §80 Conversation of Jesus with Nicodemus, click HERE and listen, or download to a device.

- Straussʼ printed work is also available online to download and read on any device.